Writing Alice

Alice was not my favourite ancestor, so I had not searched for her in all the usual places. Until I learned that in the middle years of the 19th Century, Alice Handley gave birth to (at least) nine babies, crossed the world in a sailing ship, married a Ceylonese sailor, lived on the goldfields in Australia and settled on the harsh West Coast of Aotearoa New Zealand. These events suggested Alice was a tough, resilient, and strong woman, a woman who invited further research.

The diary note to myself saying “Write Alice” went from being a reluctant task to being one of discovery and storytelling. The following is how research unfolded as I began exploring Alice’s life.

To ‘Write Alice’ meant firstly researching her life more thoroughly. “Where to start?” I thought as I sat contemplating the tiny scattered scraps of information discovered about Alice, my 3 X great grandmother.

I recalled two discussions within the Curious Descendants Club, a community of like-minded family history story writers, and my information fountain when floundering. The first was about the value of examining timelines, the second was a presentation by Dr Sophie Kay on “Narrating Your Methodology Journey” Encouraged, I began to prepare a timeline with a stern dictate to myself to document the process and progress.

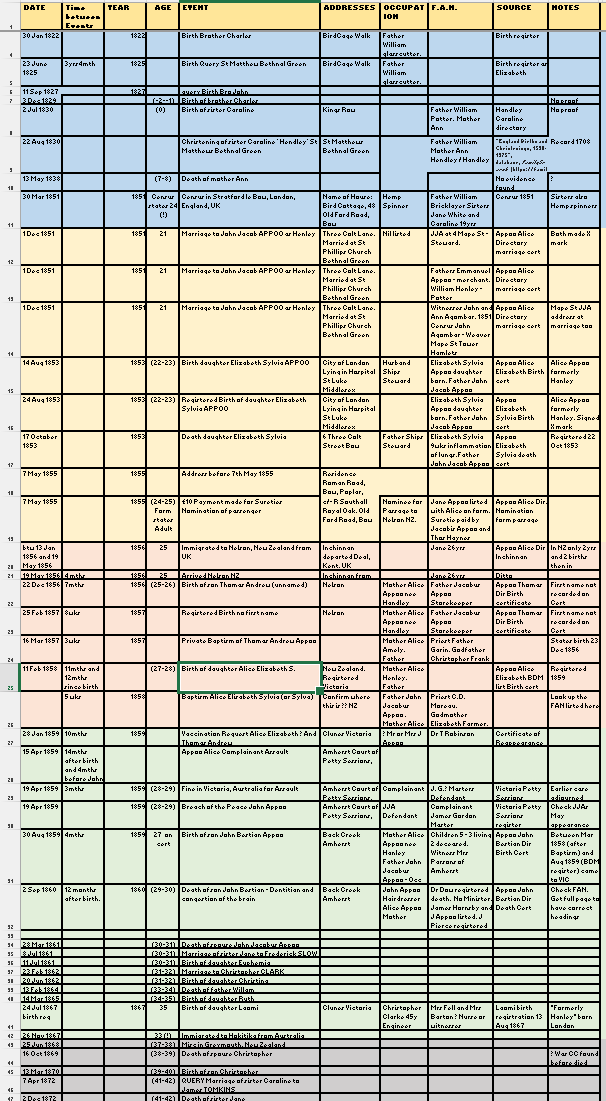

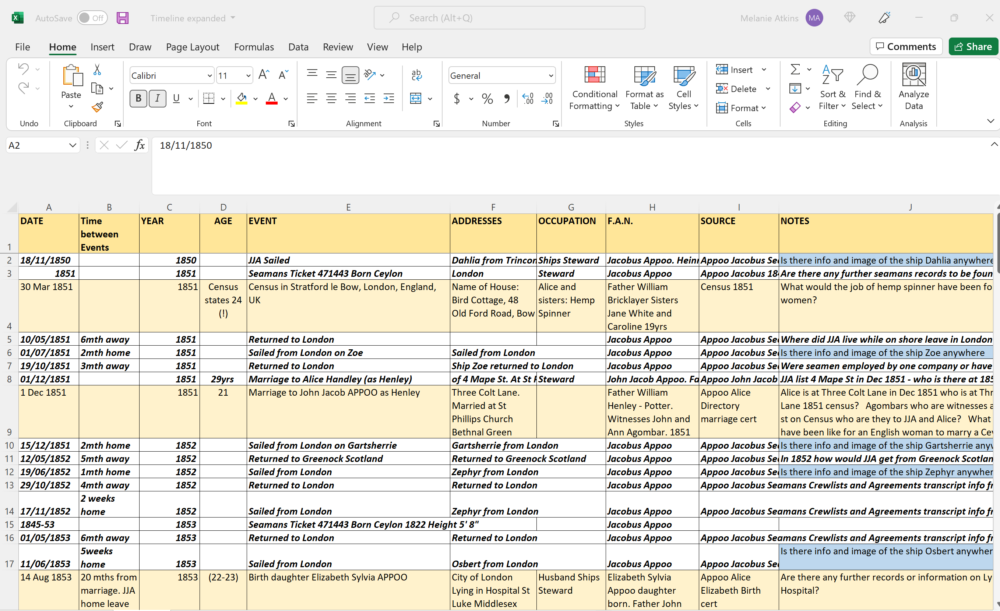

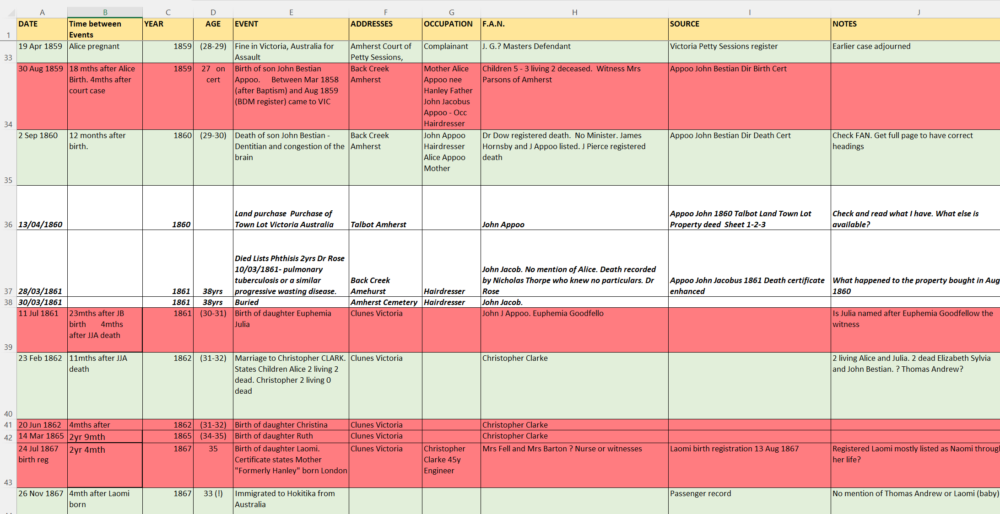

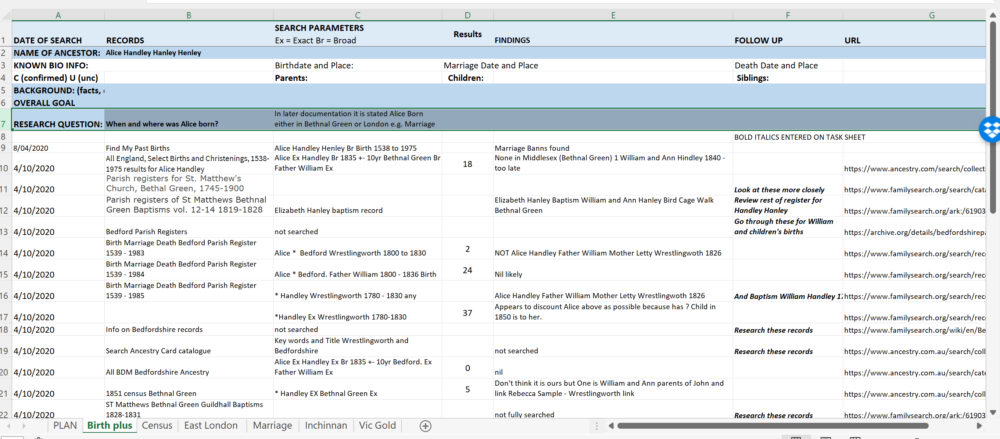

Fortunately, all details of my ancestors, including Alice, are recorded in Family Historian, a genealogy software program. I successfully produced a timeline of Alice Handley (Henley, Hanley) Appoo Clark. Converted to a spreadsheet this document is surprisingly filled with information. – too little for a weighty life story and too much to focus on with my unpractised eye and mind.

The timeline highlighted gaps in my knowledge of Alice. It showed that Alice’s birth remains stubbornly hidden, along with her life before 1851. Records of Alice’s life begin with the census in March, which lists Alice as 24 years old, and her marriage to John Jacobus Appoo in December.

Gaps and questions emerged as my eyes darted line by line through the years of Alice’s life. A helpful step was to add a column to the spreadsheet for these questions and thoughts. I remind myself to review the timeline without taking wild and irresistible tangents.

The questions began to emerge:

- Records show Alice married a man born in Ceylon on 1st December 1851. Was her wedding day a joyful celebration, or was it an arrangement that suited two people in difficult situations?

- What would it have been like for an English woman to marry a Ceylonese man in mid 19th century England?

- What does a female Hemp Spinner in 1851 East London do?

- Is there further information about the 1856 voyage of the Barque Inchinnan on which Alice travelled to Aotearoa New Zealand?

Looking over the fifty years of the timeline, I quickly realised this process needed further restriction and refinement. A narrower focus was needed. Childbirth interested me, which might make the review of information and a story more focussed.

I recalled an article by Sophie Kay mentioned in the workshop– The Pitter Patter of Ghostly Feet. A brave article describing Sophie’s own experience of miscarriage highlights what we can miss in the understanding of childbirth when reviewing records. A focus on childbirth, including child spacing, sounded manageable.

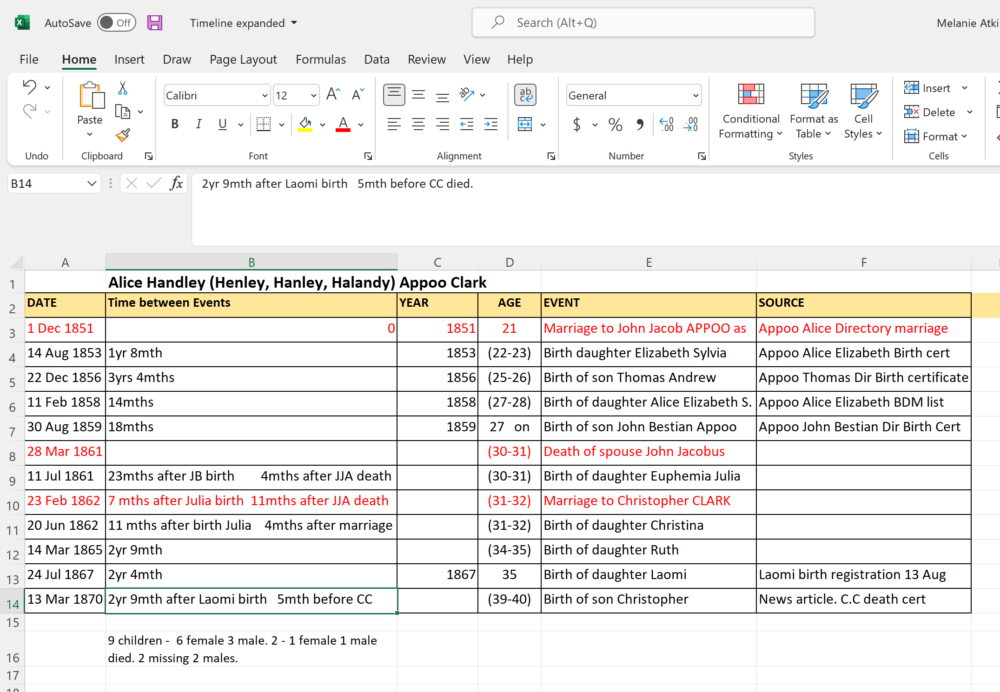

All information, except the birth of Alice’s children, was removed from the timeline. As I erased detail, I could see places to focus my research. Child spacing investigation suggested the average birth spacing was 14 months after marriage. After that, “the average birth interval is 924 days (circa 2.5 years), with a standard deviation of 455 days (about 1.2 years).” : (Malthus in the Bedroom: Birth Spacing as Birth Control in Pre-Transition England by Cinnirella Francesco, Klemp Marc & Weisdorf Jacob)

A series of calculations using Alice’s known childbirth dates ensued. In frustration, these calculations led me to count on my fingers after filling sheets of paper with scrambled numbers and dates. Eventually, the months between records of births emerged. For Alice these were: 20 months from marriage and then 40 / 14 / 18 / 23 / 11 / 27 /27 / 32 months.

As I look at these numbers, a cautionary voice tells me to take care – it is not difficult to create fictions where fact remains hidden. Hypotheses are just that until proven – they might be fact, they might be fiction. I think of my future records – a researcher may create a range of hypotheses about being missing from Australian records for two years. They may hypothesise I was stranded overseas during a pandemic; they may suggest I was staying with family in Aotearoa – New Zealand. They may never discover I was staying in country Australia with friends. In the years of travel before this, dates and places might be pieced together but not the joy, the people and life experiences of world travel.

What is discoverable from this new slimmer timeline? More questions appear, this time focussed on childbirth, including:

- Could there be more information about Elizabeth Sylvia’s birth and death at the London Lying-In Hospital?

- There is no mention of Thomas Andrew (child number three) or Laomi (baby) on the Passenger list from Australia to New Zealand. Where were they?

- The number of children stated on the certificate when Alice married Christopher Clark – two living, two dead. Alice Elizabeth and Euphemia Julia were living. Elizabeth Sylvia and John Bestian had died. Where was Thomas Andrew?

- A child registered as Laomi Clark was known as Naomi through most of her life yet called Aunt Lay by family– is the name significant?

- Did Alice have contact with her son Christopher Jnr during his short life?

Examining the birthdates of Alice’s children, I realise there may be events in the timelines of others, such as her husbands, that explain some of the anomalies. For example, her first husband, John Jacobus Appoo, was a seaman and away for long periods. Her second husband, Christopher Clark, went missing after returning to Aotearoa New Zealand.

The timeline was expanded to include information that may have impacted child spacing. Time to get the genealogical microscope – I hoped that as I scrutinised this list of records, I would discover questions and information which may give life to the bones of Alice’s life.

Work methodically. Record the question and move on – no research, no diversions. That was my process, my agreement with myself. Yet irresistible diversions did occur – some carefully saved, others a confusing tangle of notes, and others nothing at all. What happened to methodology? What happened to discipline? What happened to maintaining a thorough Research Log? The process quickly became a “How Not To”, a reminder of time wasted when there is a lack of structure and recording.

Despite the lack of consistent process, further questions did emerge once the timelines were combined:

- Is it a coincidence Alice’s husband, John Jacobus Appoo, arrived home the day his baby daughter died?

- If her husband was in New Zealand when Alice arrived on the ship, was the baby born seven months after arrival premature; was John Jacobus on the boat, or was someone else the father?

- Euphemia Goodfellow is the witness at Euphemia Julia’s birth, John Bestian’s death, and with her husband Charles, they are witnesses at the wedding of Alice and Christopher Clark. Who is Euphemia Goodfellow? Was Euphemia Julia Appoo named after her?

- Christopher Clark was reported missing by Alice, then Christopher Clark Junior was born not long after his father’s death? Was he found before he died?

Part of my plan had been to use a carefully constructed Bullet Journal to record all steps, searches and findings. A fresh notebook was purchased and set up for this purpose. At the end of Day Two, I have my Family History Bullet Journal, plus a large blank notepad, plus scraps of paper, all with scribbled and largely incoherent notes, multiple date calculations, and a reminder to get tea when I go shopping. The list of “How Not To” grows.

As I read through the questions raised by examining the timeline, I realised that each question could form a research hypothesis on a Research Log, reminding myself a research log requires discipline and a commitment to a methodology that I had not shown so far. The questions also highlight the many stories to be told.

At the end of Day Three, I have many questions, a few new leads, a commitment to research logs and a growing sense that this story is not all that it seems. There is also the realisation I will never discover the whole story – how can anyone know another person’s true thoughts, actions, and behaviours. How can we know all that is behind the records of past centuries? Yet I am intrigued and committed to “Write Alice” whatever I might discover.