The Tiny Heirloom Bottle

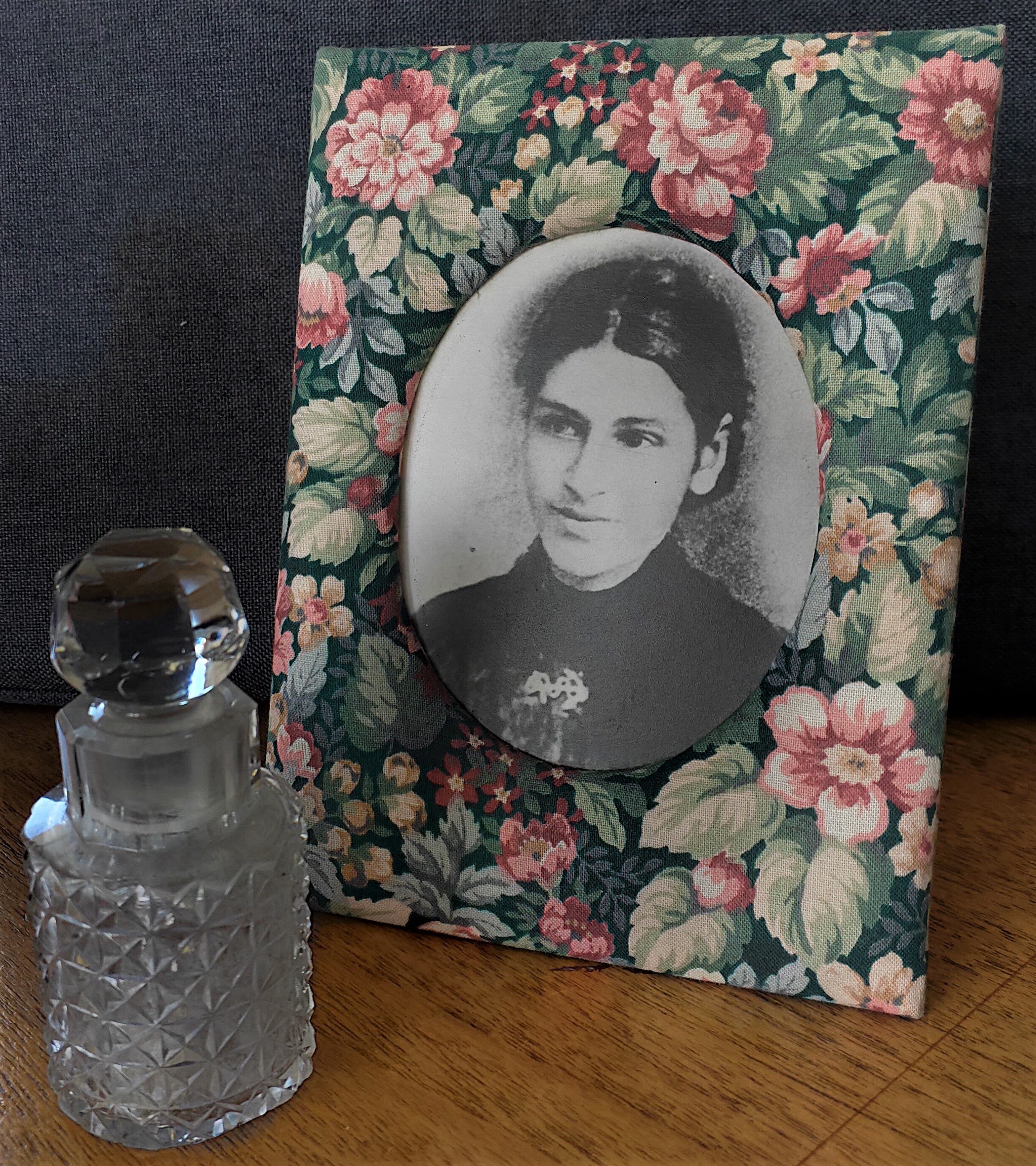

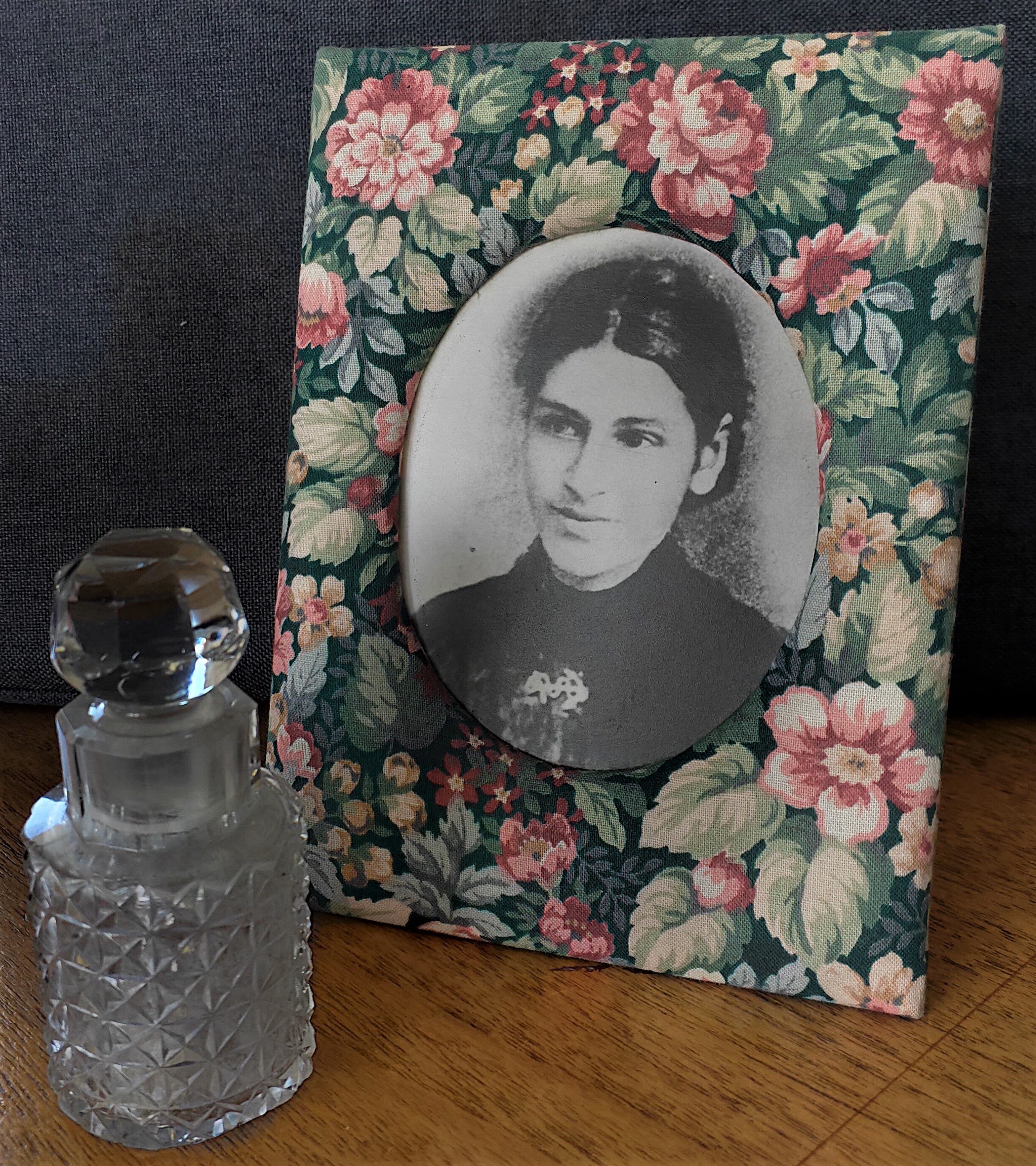

I sat at my mother’s kitchen table concentrating on the family history notes spread out in front of me. When I looked up, I could see the boats gently tugging at their moorings in the mangrove-lined river below, and cars hurrying across the coat hanger shaped bridge in the distance. A perfect, clear, blue sky day in Tamaki Makaurau (Auckland). As I sat my mother came to me and carefully handed me a small crystal bottle with a stopper that reflected dancing rainbows as it caught the light. “I want you to have this; it was Grandmother Woodfords.” Thanking Mum for the heirloom, I set it on the table and returned to what I had been doing.

Suddenly it struck me – spinning around, I looked back at the delicately patterned bottle– “You mean it was Julia’s?” “Yes. I thought you were less than enthusiastic about having a memory from your favourite ancestor” my mother responded. A bottle for smelling salts. One that would lead me to an unexpected history lesson, one that was drenched in family memories.

Euphemia Julia Appoo Woodford [1] was indeed my favourite ancestor, whether it was her short life, delicate beauty, pioneer life or a combination of, I could not say. “Where did you get it?” I squeaked, barely containing my excitement. It had been given to Mum by my great-grandmother many years before. A quick refresher of the family tree mapped the link: Lydia Ann Woodford Wilson, my great-grandmother, the oldest child of Euphemia Julia (whom we called Julia) and Edward Spencer Woodford. Lydia Ann’s oldest child was my grandmother, Eva Naomi Wilson Horn.

The gift’s connection deepened as I contemplated its past, with a curiosity to know more. I immediately took out the glass stopper and inhaled deeply, hoping for a faint tang of the ammonia, or whiff of perfume. No wisp of a fragrance remained.

Research told me that ’smelling salts’ were a combination of ammonia salts and water, or pleasant smelling scent, such as lavender. Ammonia was thought to enhance breathing, I recalled the heady, eye-watering impact of inhaling the pungent ammonia when using it for cleaning. Still used today, the substance irritates the lungs, causing a person to take a sudden inhalation, followed by rapid breathing [2] hence the everyday use in the 19th century for women prone to fainting.

Frequent fainting spells were apparently common for women, thought to be caused by wearing tight corsets and as a result of poor nutrition [4]. This widespread use of smelling salts, particularly among elite classes [5], led to the creation of an extensive range of beautiful containers to keep the salts in. Such as the one I now held.

Nomads crossing the desert had discovered ammonium salts many centuries before. Extracting a white substance, they named Sal Ammoniac, from the burned dung of their camels. It was also described in the works of Pliny and Alexander the Great [7]. Through the following centuries, it was used in diverse activities such as when using plant dyes, explosives, plant fertiliser, and smelling salts. The salts were made from animal dung until World War I, after which ammonia was made synthetically.[7]

Today, there is a resurgence in the use of smelling salts in sports to improve performance and relieve the ostensible symptoms of concussion. Its use in sports is not supported by evidence and can potentially have harmful effects, given that Ammonium salts are toxic and an irritant to delicate lung cells. [8]

“Knowing this, why would Julia use smelling salts?”

Her death certificate records that Julia died at 36 years old of heart disease that had been diagnosed 18 months earlier. It was recorded that Julia also had had Phthisis, for 8 years. The term ‘Phthisis’ was used in the 19th century to describe lung disease, commonly Tuberculosis, it is no longer used.

These diseases would likely have resulted in increased shortness of breath, difficulty breathing and overwhelming tiredness, particularly after Julia gave birth to 6 children in a short period of time.

Despite the beauty of the little bottle, it holds sadness when imagining Julia managing her illness with the smelling salts. Julia’s health records have not been found so it is not known what other treatment may have been possible in the remote West Coast of Aotearoa New Zealand, in the late 1800s.

Smelling salts were, and remain useful as an expectorant, to loosen secretions and help clear lungs.[9] [7] In 1928, The New Zealand Herald listing ‘Smelling Salt Secrets’ recommends the ability to clear the “stuffy” feeling caused by a cold.[10] These effects of smelling salts may have given some relief to Julia.

A bottle for holding smelling salts is also a reminder of how women were viewed at that time. The use of smelling salts was almost always only associated with women. [5] Reinforcing the view that women were of weak nature. An article in the 1906 Bush Advocate, quoted a “learned physician” who suggested women are becoming “a veritable smelling salts slave”[12], describing intoxication, as an “absolute vice”[12].

The article goes on to suggest that husbands have been shocked when encouraged to try the salts and discovered the impact the salts have on their wives.[12] In the Lyttleton Times in 1894 a ”New York physician” is quoted as identifying smelling salts as the cause of a prevalence of deafness amongst his women patients, describing one as using the salts for a nervous attack. [13]

It was also a time when fainting was seen as an outcome of being fragile, not as a symptom of a condition that should be investigated.

Being gifted that tiny bottle has expanded my understanding of women in the late 19th century: the life Julia might have led; and the pervading view of women at that time as fragile and weak. All epitomised through the history of smelling salts.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

[1] Atkins Melanie, ‘Julia’, Voiceless Echo, Jun. 14, 2022. https://voicelessecho.com/julia/ (accessed May 10, 2022).

[2] ‘Smelling salts: What are they, uses, and are they bad for you’. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/smelling-salts#risks (accessed May 14, 2022).

[3] ‘Smith and Caugheys Page 16 Advertisements Column 2 , Page 16 Advertisements Column 2’, New Zealand Herald, vol. LXV, no. 20114, p. 16, Nov. 27, 1928.

[4] ‘Faint of Heart | Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum’, Jun. 17, 2016. https://www.cooperhewitt.org/2016/06/17/faint-of-heart/ (accessed May 12, 2022).

[5] ‘Smelling Salts’, Eighteenth-Century Literature, 2011. http://eighteenthcenturylit.pbworks.com/w/page/70599154/Smelling%20Salts (accessed May 18, 2022).

[6] ‘My Victorian to Edwardian Antique Smelling Salts Bottles | Antiques Board’. https://www.antiquers.com/threads/my-victorian-to-edwardian-antique-smelling-salts-bottles.25742/ (accessed May 18, 2022).

[7] ‘Nushadir. The salt of Ammon or Amun: an appropriate practice of Inner’, Fontana Editore. https://fontanaeditore.com/blogs/nitrogeno/nushadir-the-salt-of-ammon-or-amun-an-appropriate-practice-of-inner-alchemy (accessed May 18, 2022).

[8] P. McCrory, ‘Smelling salts’, British journal of sports medicine, vol. 40, pp. 659–60, Sep. 2006, doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2006.029710.

[9] ‘ammonium chloride | Formula, Uses, & Facts | Britannica’. https://www.britannica.com/science/ammonium-chloride (accessed May 18, 2022).

[10] ‘Smelling Salts Secrets. , Smelling Salts Secrets.’, New Zealand Herald, vol. LXV, no. 19868, p. 6, Feb. 11, 1928.

[11] ‘Smelling Salts Page 10 Advertisements Column 1 , Page 10 Advertisements Column 1’, Manawatu Times, vol. XLIX, no. 2272, p. 10, Oct. 17, 1925.

[12] ‘Danger in Smelling Salts. , Danger in Smelling Salts.’, Bush Advocate, vol. XVIII, no. 501, p. 7, Aug. 29, 1906.

[13] ‘Flowers and Smelling Salts. , Flowers and Smelling Salts.’, Lyttelton Times, vol. LXXXI, no. 10356, p. 2, May 24, 1894.

This was excellent Mel. Well written and an easy and informative read. This type of story would work well as a competition piece.

Thank you for the encouragement.