Aunt Lay

Seeking stories of the women in my past, I looked for the strong women; the activists, the suffragettes. Naomi’s story taught me that strength and resilience can be found in everyday life.

I had always been drawn to Naomi Clark Connell (my 2X grandaunt) – a woman of courage and tenacity who made a life for her family in the pioneer towns of Aotearoa New Zealand (NZ). A woman who worked in domestic service, who raised four children on her own. A woman who saw three sons go to war and return forever changed.

Naomi lived in a time before women were able to vote, before it was acceptable for a woman to live apart from her husband, and before it was acceptable for a single mother to raise her children alone. Naomi lived in a time when NZ was newly occupied by colonial settlers, when the Māori people, the Tangata Whenua, were still fighting fervently for their land.

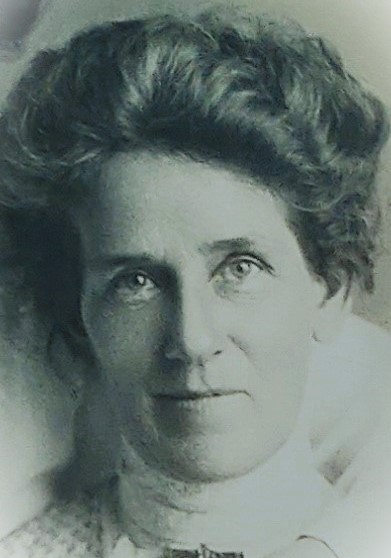

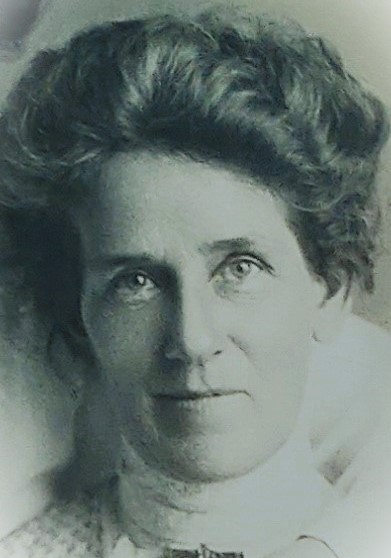

My interest in Naomi’s life had been captured through family photographs and handed down family reminiscences. When I look at her photographs, I see a woman staring straight at the lens, her dark eyes emanating warmth and kindness, the lines on her face enhancing a sense she is wise and confident. Her soft wavy hair, styled similarly in each image, despite the years between, hinted perhaps at a woman who spent more time on others than on herself.

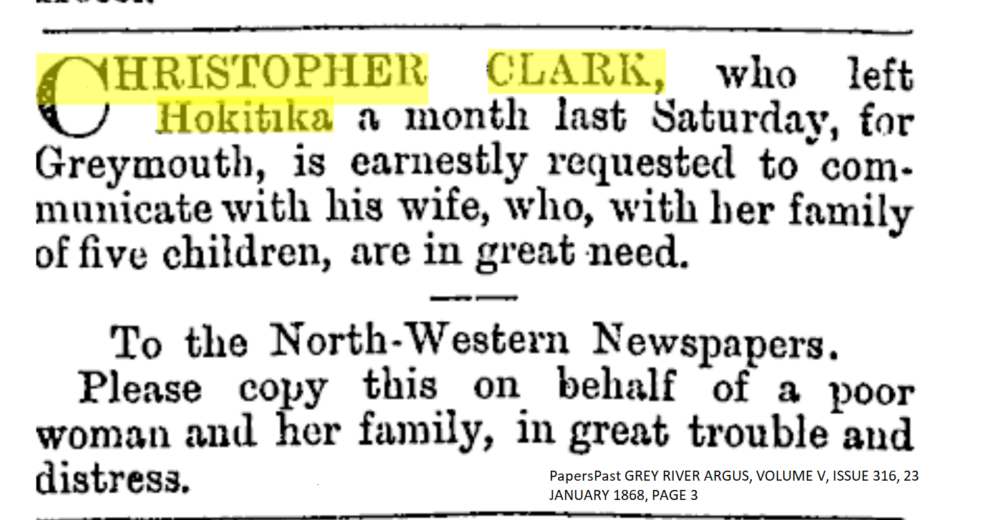

From her hardy beginning – born in 1867 in a newly established gold mining town in Victoria, Australia – Naomi survived adversity without public acknowledgement. Invisible from birth – named Laomi Clark [1], she was not listed with her siblings when her family made the rugged sea crossing from Melbourne, Australia to Hokitika, NZ in November 1867 [2]. Living with her mother and siblings in the remote coal mining town of Taylorville, NZ, Naomi only appears in records when her mother requests assistance for her children when her husband is missing[3] and again after their father dies in a mining accident[4].

Was it observing the strong spirit of her mother, who maintained her young family after the death of her husband (and breadwinner)[4], that encouraged a young Naomi to travel alone to Reefton, a town well north of her home? In the late 1800s travel to Reefton may have been by barge up the river, Cobb & Co horse and coach, or possibly taking a ride with someone also travelling in that direction[5][6]. With a rail line only just being constructed the alternatives would have meant a long and rigorous journey through mining towns, verdant farmland, and dense native forest. Naomi travelled in a time before there was electricity at the stops along the way. Reefton would soon become famous as the first town in the Southern Hemisphere to have electricity in 1888,[7] most towns did not have electricity until after World War I.

In Reefton, Naomi was employed in domestic service. In the late 19th century this was often gruelling work, long hours, and poor pay. “A servant had to be physically strong and have a sense of subservience”[8]. Women reported working 6am to 11pm with a half day, or sometimes only an evening off a week. If time off was given the “mistress” would often dictate what could be done during that time. These were such accepted employment conditions that in 1896 when a bill was introduced before the NZ parliament to give servants half a day off a week – it was laughed at. The servant role had been imported by the early English emigrants; a role so popular the number of positions could not be filled. In NZ even middle-class families often had at least one servant, usually a woman, working many roles that might have included cooking, cleaning, childcare, milking cows, and gardening.

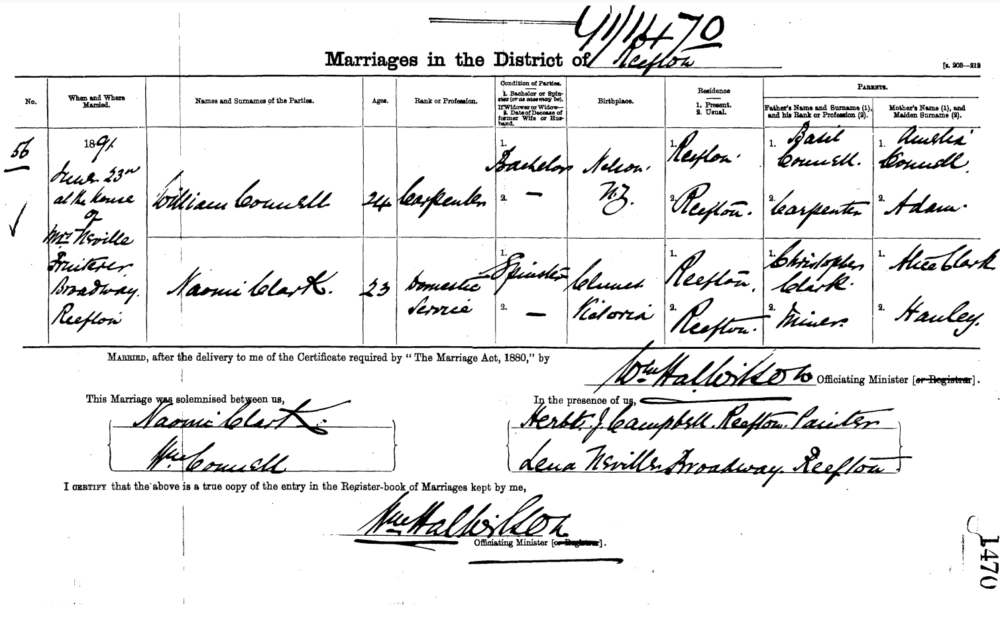

It was in Reefton in 1891 that Naomi married William Connell, at the home of ‘Mrs Neville, Fruiterer’[9]. This was possibly where Naomi worked as a ‘strong but subservient’[8] domestic servant. Shortly after marrying, she had her first baby, likely a long way from her mother and sisters.

Naomi’s strength would again have been tested when with her new baby daughter, Amelia Alice, she followed her husband William Connell on a lengthy journey from Reefton in the South Island to Palmerston North in the North Island of NZ. Crossing the treacherous Cook Strait, still today “considered one of the most dangerous and unpredictable waters in the world”[7]. In the following seven years, Naomi gave birth to three sons, [8] distanced from her family, from support, and if family accounts are accurate, with a husband who struggled with alcohol issues. During this time Naomi would be further tested by the death of her younger brother Christopher and older sister Julia.

Early in the 1900s, Naomi separated from her husband and moved to Whanganui with her four young children. The life of a single mother would have required toughness and determination in the early 20th century when widowhood was the only acceptable form of single parenthood. Husband William appeared to remain on the North Island in and around Palmerston North until he died in an unexplained house fire in 1928 [9].

Whanganui is now as it was then, a town dominated by the river running through it. The water comes from the nearby ocean through gorges and the dense wild interior to the high slopes of the volcano Tongariro. A river so important to Māori and Pakeha (pale person[10]) alike that in 2017 it became the first river in the world to gain legal personhood.[11] A river that in the early 20th century was filled with paddle steamers cruising, goods being transported, people being ferried and the local Māori people struggling to continue their lives along the river.[12]

The town of Whanganui grew on the bank of this river described as the “Rhine of New Zealand”[13]. Farming, industry, and tourism encouraged early expansion. This was a town that wanted to go places, a place imitating the recollection its inhabitants had of their English roots. Tall ornate buildings, and an array of shops promoting a lavish array of foods, clothing, and home goods from England. Trams ran down the main street, even a grand domed opera house with a large portico supported by pillars across the front[14].

It was in this town Naomi lived the rest of her life after coming with her four young children in the early 1900s. It was in this thriving early tourist town that my grandmother remembered “Aunt Lay” teaching her how to make boiled sweets at her shop in Whanganui. No evidence has been found of Naomi owning a shop – but there were several sweet shops in the town to entice tourists, where she may have worked.

My grandmother and great-grandmother spoke fondly of Aunt Lay (Naomi). The depth of the bond between my great-grandmother and Aunt Lay is evidenced by the naming of her first daughter, Eva Naomi. Family stories describe her taking care of her niece Lydia (Lydia Ann Woodford my great-grandmother), a young girl whose mother, Julia, died when Lydia, the oldest of her six children was just 9 years old. Bringing Lydia from the remote west coast to the north island town of Whanganui, the town where Naomi spent much of her adult life.

Naomi’s greatest test came in 1914 with the outbreak of the First World War. Each of her children was of age when the Great War came. Over the following four years, her sons and son-in-law sailed across the world in troop ships crowded with the young men of NZ, to serve in the war mistakenly called the ‘war to end all wars’.

The stories of war are often told through the voices of the young men who fought, or the (often male) historians and politicians who interpreted their lives. What about the mothers I wondered? War records name Naomi Connell, Mother, as the only next-of-kin for all three boys.

As a mother, I would have valued a conversation with Naomi. How did she bear those years? Likely she would recall “What could we do, mothers were powerless. It was our duty to the mother country to bear it as our sons left and it was their duty to enlist. Our allegiance was to England, to the King, to defend the Empire. The boys were excited about a big adventure. Billy (Christopher William) [15], the oldest and first to enlist just four days after NZ entered the war. Then it was Graham (Graham Basil)[16] and Leslie (Leslie Herbert)[17] along with my son-in-law Robert (Millar Scott)[18] After they sailed, every day of those war years was spent waiting.”

Naomi, like 100,000 other NZ mothers, would have spent those years waiting for postcards from the boys; waiting for news of the war that took weeks to get to NZ.[19] Waiting for that knock at the door, the dreaded telegram. Comforting other mothers that answered that knock, feeling guilt at your relief that it is not your son.

Amelia, Naomi’s only daughter would also have needed Naomi’s strength, love, and support through her wartime sorrow and loss. For Amelia, the celebration and joy of marriage were closely followed by grief. Her new husband was killed in France soon after he arrived in 1916.[18]

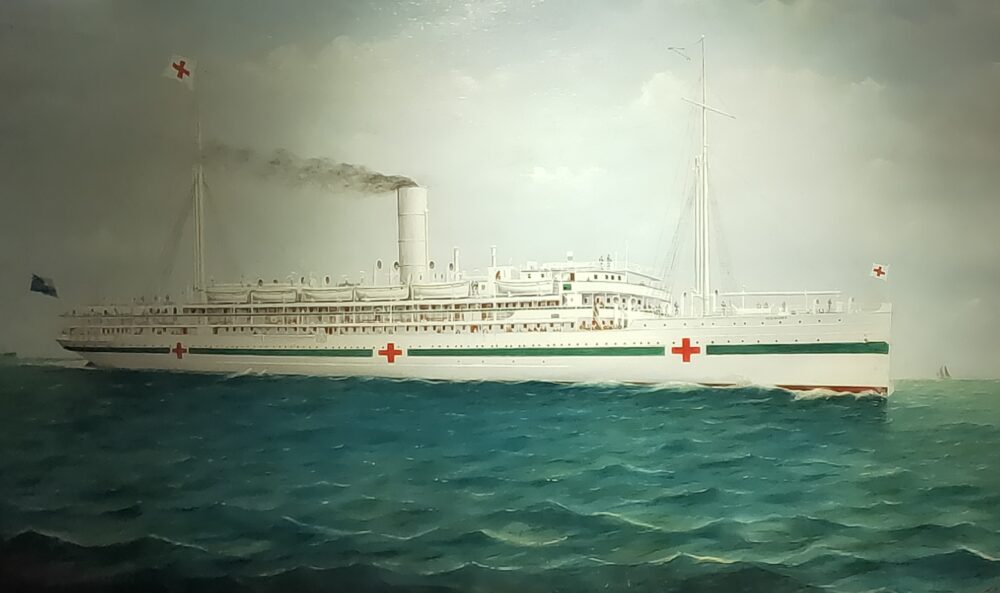

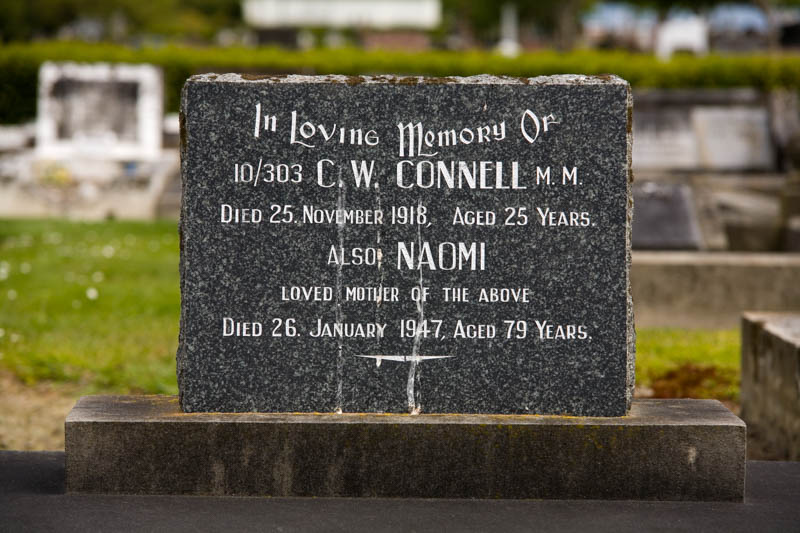

When Naomi received the news about Billy she likely felt relief. “Slightly sick”[20]pg3 the army Doctor had stated, adding that he was being transferred to England. Billy was safe but it was not to last. Naomi received the unexpected news that Billy had been seriously injured in a motorcycle accident. Billy’s war was over, he would be discharged from the army and returned to NZ. A long journey, as the hospital troop ship Marama, crossed the world, returning damaged and changed boys home. Not long after arriving back in Whanganui the cruelty of the deadly Influenza pandemic chasing soldiers home struck Billy. On 25th November 1918 Billy, just 25 years old, died of complications from Influenza.[21]One can imagine the depth of her love and grief on discovering it was Billy that Naomi was buried with after her death in 1947.

At the war’s end, after serving in Egypt and then the Western Front, Graham and Leslie returned home. Graham to Whanganui, Leslie to Australia. Escaping war, but not tragedy, it was Naomi who comforted Leslie when his wife[22] and baby died in 1929[23] soon after childbirth. Naomi travelled from her Whanganui home in NZ to Colac, a town in the Western District of Victoria, Australia, to be with him but could not persuade him to return with her. Naomi’s journey would have been days by ship and train. Passenger air travel between the two countries was still twenty years away[24].

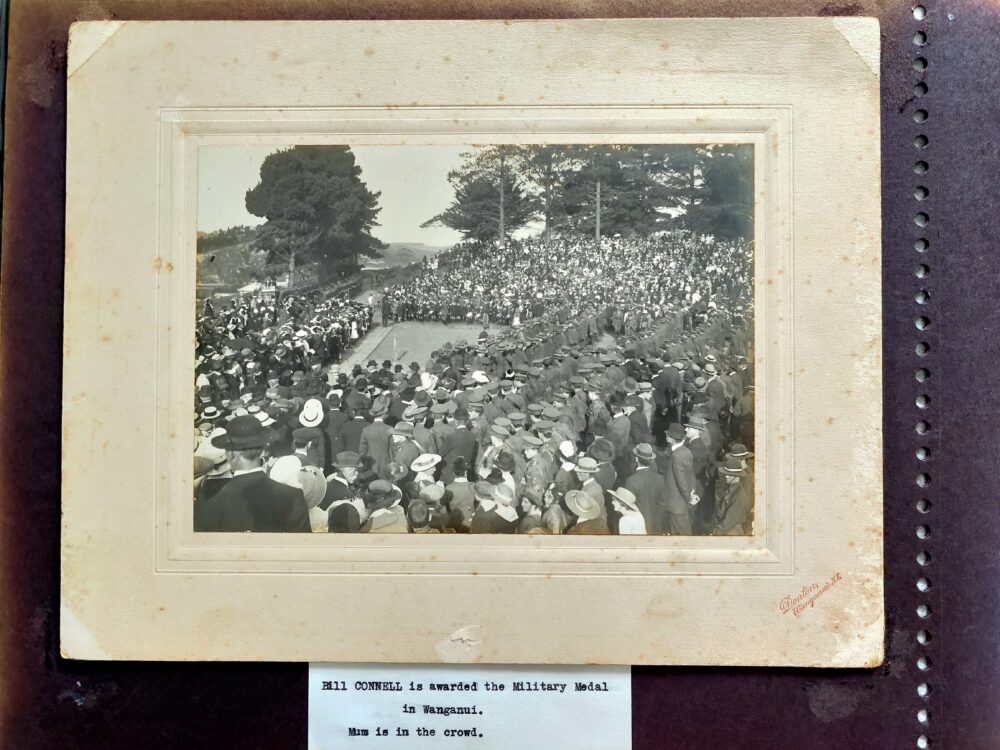

Learning the stories of Naomi’s sons in wartime I was reminded of a photograph my grandmother kept. A large black-and-white image of many people gathered in an amphitheatre-shaped park in Whanganui. Visible are groups of men in uniform, drummer boys in suits carrying drums, men in their suits and hats, and women in a wide array of hats and fashion. This occasion in family recollection was when the Governor General presented a medal (the 1914 – 1915 Star Medal) to Naomi’s oldest son Christopher William (Billy) Connell.[25] Naomi and my grandmother were present at the event. Later my grandmother would proudly tell her daughter she could pick herself out in the photograph by her hat.

The event reported in the local newspaper, described both the recognition of Billy’s war service and the laying of a foundation stone for the Sarjeant gallery. This grand art gallery, a further addition to the town’s imitation of an England left behind, was a statement of wealth made possible through a substantial donation by a local farmer. Built with local white Oamaru stone the gallery opened in 1919 and remains a part of the Whanganui community today.[26] Coming so soon after her son’s accident and return it is easy to see why this poignant celebration was recalled as ‘Billy’s’.

The war to end all wars was not to be. Before her death in 1947, Naomi was to live through another world war and see her son Graham again called up for active service.[16]

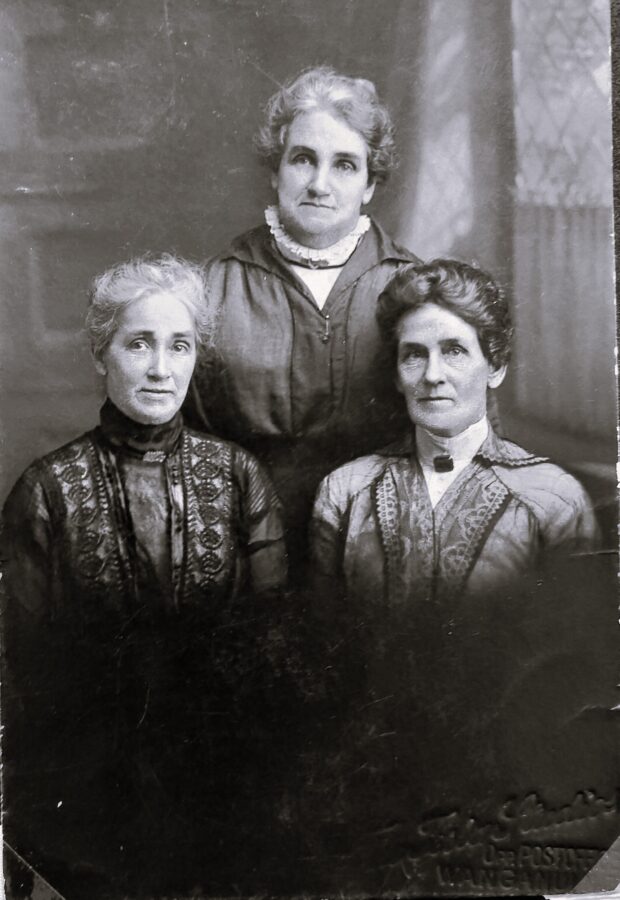

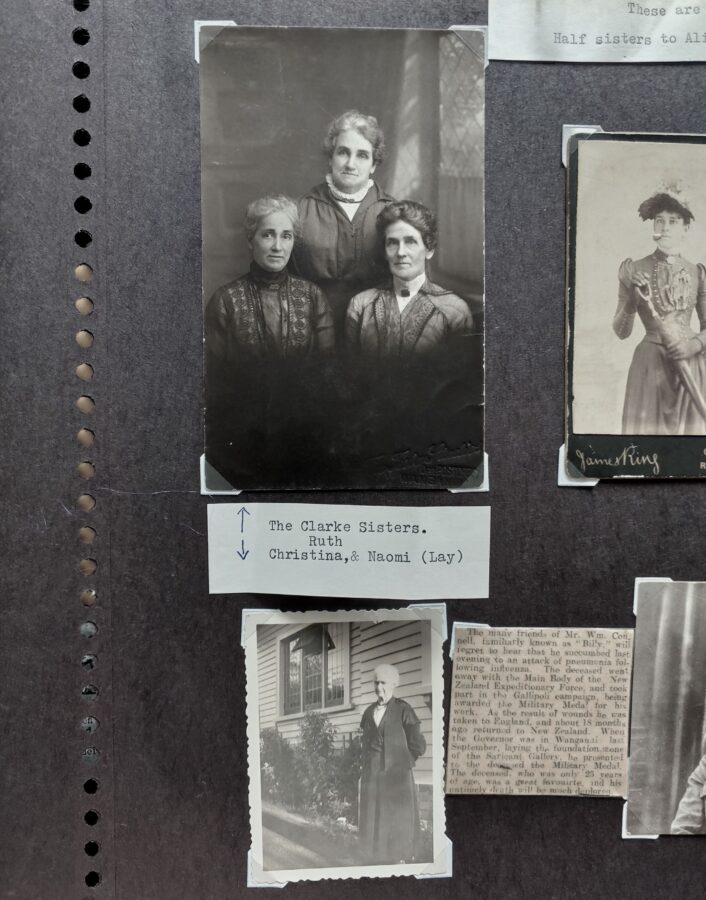

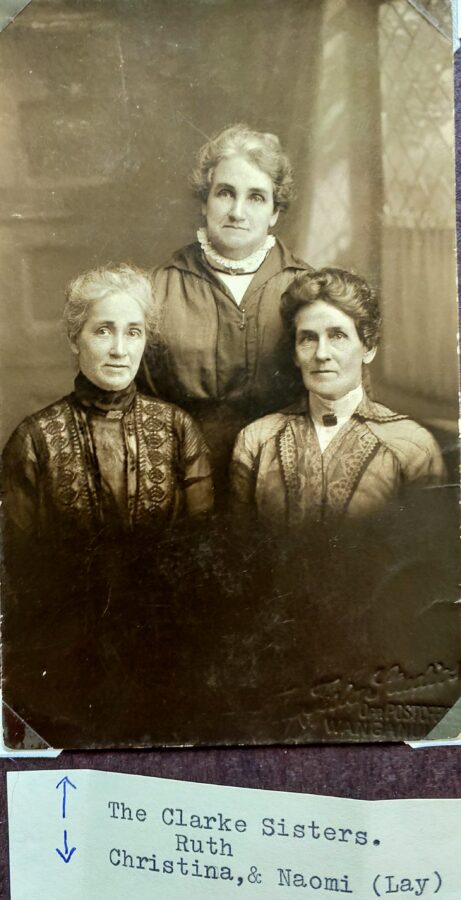

I am drawn back to the photographs, a triptych testament to Naomi’s life. The earliest, a small carte-de-visite, a young Naomi looking determinedly to the distance, in the next with Amelia, a young woman with her arm around her mother smiling at the camera, Naomi seated smiling softly. The final is an older Naomi with her two sisters Ruth and Christina, calmly looking into the camera.

As I study the final image, I see a woman who has faced adversity yet retains warmth and strength. A woman who gave love and care to her family through the many challenges they each faced. A woman who may not have been politically active yet challenged the norms of women of her time including choosing to raise her children alone. A woman I am proud to call my ancestor.

Your memory lives on Aunt Lay.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

[1] ‘Laomi Connell Birth Certificate 1867’.

[2] Rae Atkins, ‘Clark Passenger Gotheburg’.

[3] ‘Request Assistance for Clark family’, Grey River Argus, vol. V, no. 316, p. 3, Jan. 23, 1868.

[4] ‘Notice Christopher Clark death’.

[5] N. Z. M. for C. and H. T. M. Taonga, ‘Servants in the 19th century’. https://teara.govt.nz/en/household-services/page-1 (accessed Sep. 13, 2022).

[6] Marriage Register Reefton, ‘Marriage certificate Connell William and Clark Naomi’. BDM NZ, Jun. 23, 1891.

[7] ‘Cook Strait | NZHistory, New Zealand history online’. https://nzhistory.govt.nz/keyword/cook-strait (accessed Oct. 12, 2022).

[8] BDM New Zealand, ‘Connell William and Naomi Births’. [Online]. Available: [https://www.bdmhistoricalrecords.dia.govt.nz/search/search?path=%2FqueryEntry.m%3Ftype%3Dbirths](https://www.bdmhistoricalrecords.dia.govt.nz/search/search?path=%2FqueryEntry.m%3Ftype%3Dbirths)

[9] ‘Connell William Accidents & Deaths. , Accidents & Deaths.’, Ashburton Guardian, vol. 48, no. 178, p. 4, May 10, 1928.

[10] ‘Pākehā: The real meaning behind a beautiful word’, Te Papa’s Blog, Sep. 14, 2018. https://blog.tepapa.govt.nz/2018/09/14/pakeha-the-real-meaning-behind-a-beautiful-word/ (accessed Nov. 11, 2021).

[11] ‘Innovative bill protects Whanganui River with legal personhood – New Zealand Parliament’. https://www.parliament.nz/en/get-involved/features/innovative-bill-protects-whanganui-river-with-legal-personhood/ (accessed Sep. 29, 2022).

[12] B.- https://bsd.nz, ‘History of Whanganui | Discover Whanganui’. https://discoverwhanganui.nz/guides/history-of-whanganui/ (accessed Sep. 13, 2022).

[13] ‘Tales of the Whanganui: Rediscovering the “Rhine of New Zealand”’. https://a-maverick.com/blog/tales-of-the-whanganui-rediscovering-the-rhine-of-new-zealand (accessed Sep. 29, 2022).

[14] ‘Wanganui Opera House | Heritage New Zealand’. https://www.heritage.org.nz/the-list/details/169 (accessed Sep. 29, 2022).

[15] ‘Women’s Mobilization for War (New Zealand) | International Encyclopedia of the First World War (WW1)’. https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/womens_mobilization_for_war_new_zealand (accessed Oct. 11, 2022).

[16] P. scheme=AGLSTERMS. AglsAgent; corporateName=National Archives of Australia; address=Queen Victoria Terrace, ‘CONNELL, Graham Basil – WW1 3/1762 – DPF [Duplicate Personnel File] | Discovering Anzacs | National Archives of Australia and Archives NZ’, Oct. 22, 2014. https://discoveringanzacs.naa.gov.au/browse/records/583609 (accessed Oct. 13, 2022).

[17] P. scheme=AGLSTERMS. AglsAgent; corporateName=National Archives of Australia; address=Queen Victoria Terrace, ‘CONNELL, Leslie – WW1 23/1355 – Army | Discovering Anzacs | National Archives of Australia and Archives NZ’, Oct. 22, 2014. https://discoveringanzacs.naa.gov.au/browse/records/649454 (accessed Oct. 13, 2022).

[18] P. scheme=AGLSTERMS. AglsAgent; corporateName=National Archives of Australia; address=Queen Victoria Terrace, ‘SCOTT, Robert Millar – WW1 28545 – Army | Discovering Anzacs | National Archives of Australia and Archives NZ’, Jul. 22, 2014. https://discoveringanzacs.naa.gov.au/browse/records/540621 (accessed Oct. 13, 2022).

[19] ‘Keeping the home fires burning | WW100 New Zealand’. https://ww100.govt.nz/keeping-the-home-fires-burning (accessed Oct. 13, 2022).

[20] P. scheme=AGLSTERMS. AglsAgent; corporateName=National Archives of Australia; address=Queen Victoria Terrace, ‘CONNELL, Christopher William – WW1 10/303 – Army | Discovering Anzacs | National Archives of Australia and Archives NZ’, Oct. 22, 2014. https://discoveringanzacs.naa.gov.au/browse/records/585952/ (accessed Oct. 13, 2022).

[21] ‘Reality of war for our boy Billy’, NZ Herald. https://www.nzherald.co.nz/whanganui-chronicle/news/reality-of-war-for-our-boy-billy/CSBPC3EA3MXYOUSZDWMVBMLB6A/ (accessed Sep. 28, 2022).

[22] ‘Ivy Wheadon Connell (1902-1929) – Find a Grave…’ https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/156580925/ivy-connell (accessed Oct. 13, 2022).

[23] ‘Connell, William Graham “Find A Grave Index”’. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:Q291-FVRJ?treeref=LJCH-XZD (accessed Oct. 13, 2022).

[24] N. Z. M. for C. and H. T. M. Taonga, ‘Air travel International Destinations’. https://teara.govt.nz/en/aviation/page-6 (accessed Oct. 11, 2022).

[25] ‘Visit of the Governor= General. , Visit of the Governor= General.’, Wanganui Chronicle, vol. LX, no. 17087, p. 4, Sep. 15, 1917.

[26] ‘Sarjeant Gallery Whanganui | Background’. https://sarjeant.org.nz/background/ (accessed Oct. 13, 2022).