Doctor and Suffragist Dr Marguerite Alice Christian Douglas

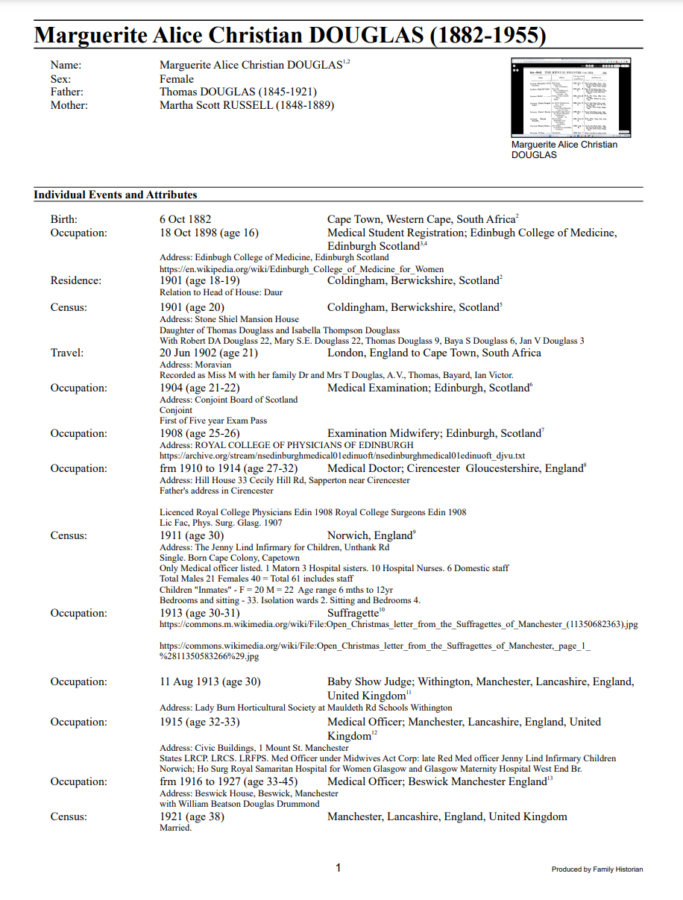

NOTE: As I began to write this I believed Dr Marguerite Alice Christian Douglas, was a direct ancestor. Through research for this story, I discovered it was not her mother but her stepmother Isabella Thompson Horn to whom I have an ancestral connection. Fascinated by the story of Dr Douglas and her career I continued. In our modern world of blended, changing family structures I embrace her as family.

While the story and many details contained within are factual it is blended with fiction, including telling the story from Dr Douglas’s perspective. To assist with clarity an appendix contains a bibliography and the facts discovered about Dr Douglas.

1933

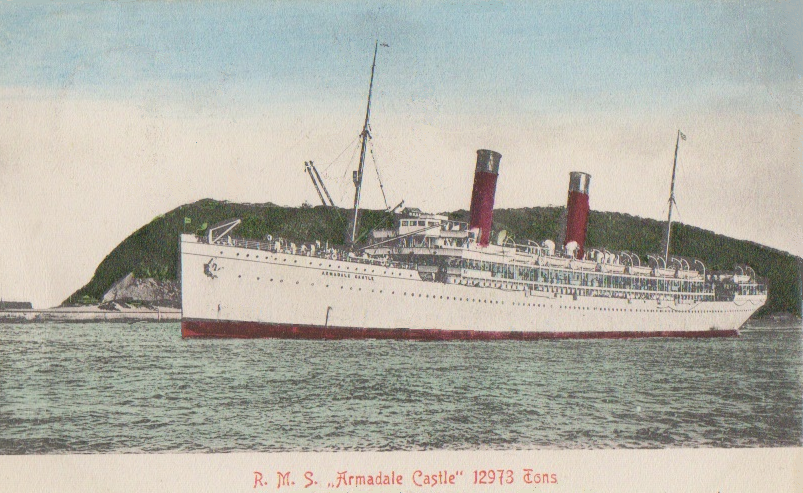

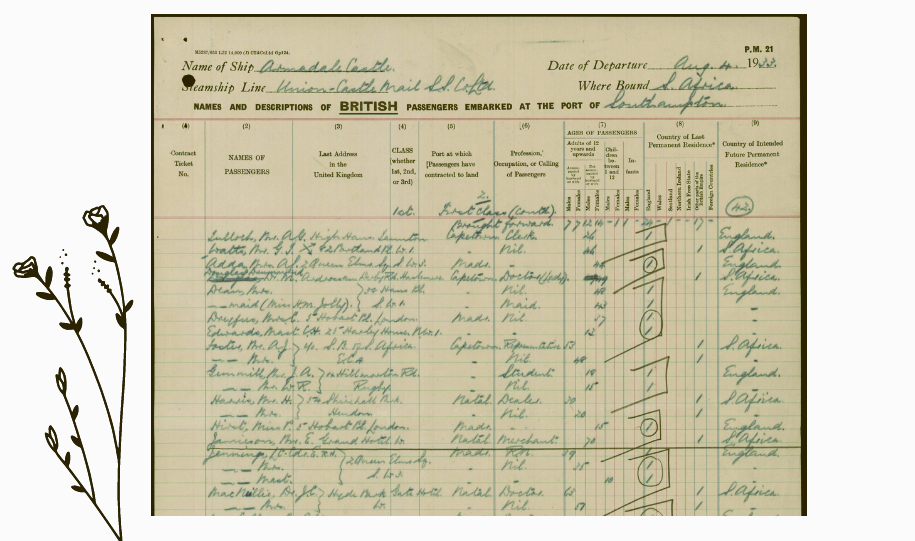

I, Dr Marguerite Alice Christian Douglas-Drummond prepare to return to my beloved homeland of South Africa. There is little time to contemplate the past years as the August 4th sailing date draws near. [1]. A new chapter of my life is about to unfold, and I look back with pride at my time in England. I am one of a generation of women who challenged societal standards and paved the way for women of the future.

On beginning my medical training in the early 1900s [2] there were few women in medicine. It was not an easy path. Yet being a woman doctor is a privilege, one must not let the obstructions and prejudices women face deter one. I well know that my skills and knowledge are as valuable as any man and I am determined to continue to use those hard-won skills as long as I am able.

Young women ask me if the path was difficult. I confess I find it difficult to answer that question without knowing exactly what is meant, for you see it was not an easy path as a woman, a suffragist, nor as a doctor, but it was a necessary one.

Was it difficult leaving my beloved South Africa in the early years and returning to Great Britain? Yes, it certainly was. To leave behind one’s home and everything familiar is never an easy thing to do.

Was it difficult studying medicine as one of the few women entering the profession? Most definitely. Becoming a doctor, as a woman, abounded with obstacles placed in our path by fellow male students, male doctors, news reporters and even the public who would feel it necessary to impede our path.[3] I was determined to succeed. Despite the derision and endless scrutiny faced, I qualified. Did you know I was one of only four women who graduated in our final year? [4]

And what about the fight for women’s suffrage? It was a long struggle and we faced opposition from all sides. At times progress was painfully slow, yet we took up any and every opportunity to put our case. The dissent within the movement created difficulties at times, while we suffragists wanted suffrage – the right for all women to vote in political elections – we sought resolution by peaceful and lawful means.[5] Emmaline Pankhurst and her fellow suffragettes used more militant sometimes violent methods. We persevered until finally in 1918 a minor victory – the vote was granted to some women. It was not until 1928 that we finally achieved our goal – votes for all women in Britain. [6]

Do not forget that within each struggle were moments of achievement, delight, and joy. Moments when the strength of women shone brightly. As I provide guidance, I remind those young ladies starting out to remember that while there will be difficulties along their path, there will also be moments of great triumph and celebration.

Graduation as a Doctor was a time of celebration and triumph. In October 1908 I was one of only seventeen students in Edinburgh to graduate.[7] Such pride I held in that achievement, particularly coming from a family of doctors – all men before myself of course. Graduating were thirteen men and four women of the eighty-two students. The students hailed from all corners of the British Empire. [7] The memory of graduation day still fills me with joy. While unseasonably warm, it was a delightful day. Friends and family were vying for space in a hall gaily awash with chatter and laughter, giving such a festive air. The people of Edinburgh, particularly the women, turned out in large numbers, while an auspicious day for graduates, it was a day of entertainment for the townsfolk. Can you imagine the colourful spectacle looking over the sea of hats and colourful gowns as we accepted our certificates?[4]

For women studying at the Edinburgh College of Medicine for Women, indeed for women studying medicine throughout the Empire, we faced considerable scrutiny. To prove we were fully equipped for the profession we had to work harder than our male counterparts in every area of study. We often had to prove ourselves not only to men in medicine but to our own fathers and brothers. There was a prevailing view that our delicate female sensibilities were not up to the task, a fear that this would make us more masculine. The demand by the women’s movement of “no favour but no handicap” fell on deaf ears in medicine. [3] For a woman to receive the Triple Qualification, determining one to be a fully qualified doctor, was a triumph for all women.

As I said earlier, I was part of a generation of women breaking new ground and I met many strong women who were fighting for the rights of women in all spheres. While still a medical student, I was fortunate enough to cross paths with Dr Elsie Inglis, a true role model and mentor for many women, including myself. Her influence was felt long after her death in 1917. [9]

The formidable Dr Inglis along with her father had established the Edinburgh College of Medicine that I attended. For a time, Dr Inglis was a lecturer in Gynaecology at the college and an excellent teacher. How privileged students were to attend her classes.[10] In the year I began my medical training Dr Inglis joined with her colleague Jessie MacGregor and established ‘The Hospice’ a hospital for poor women and babies of Edinburgh.[6][11] Established in a grand old building right on the High Street, it was a notion unheard of at the time – a hospital staffed entirely by women. [12]

Dr Elsie Inglis fought for what she believed in and encouraged her students to do the same. particularly the rights of women. Her tall stature and direct gaze enhanced her standing, a daunting woman whom I recall lobbied strongly for women doctors to be paid equally to their male counterparts. [10] I thought of her during my time in Manchester through the years of the Great War, when there was a discussion about an increase in my salary. My annual salary of £300 was eventually increased to £350 per annum, because “lady doctors were difficult to secure” [13] at that time. I was flabbergasted to see this written up in the local news with the headline “A Profession Which Gains From the War” [13]. I was simply outraged knowing my male counterparts had long been earning a yearly salary of £500.

I had the privilege of meeting and working with many wonderful women like Dr Elsie Inglis. I well remember attending a Norwich Women’s Suffrage meeting where I had the opportunity to hear Mary Bell give a lecture.[14] Mary Bell like Elsie Inglis (and in small part myself) distanced themselves from the more militant suffragettes, believing the use of peaceful and educational methods was the way to achieve suffrage for women. It was a stirring lecture, reported as “historical and argumentative,” in the newspaper of the movement “Womanly Work” [15] I can attest it was met with enthusiastic applause from the audience – including myself. Dr Bell also pointed out the inequities of pay for doctors and highlighted the anomaly that as women we could not vote, but as doctors, we could certify a man unfit to vote. [16]

Moving to Manchester before the war, I discovered a busy and expanding city. A hub for social reform movements, including Women’s Suffrage. Here I once again met and worked with women passionate about the rights of women. One could not help but be drawn to the cause here, the home of Emmaline Pankhurst: the city where Dr Margaret Ashton was elected as the first woman councillor: [17] and where Miss Emily Hobhouse published letters in the Manchester Guardian to bring word of the dreadful conditions of those in British Concentration Camps in South Africa to the attention of the public.[18] [19]

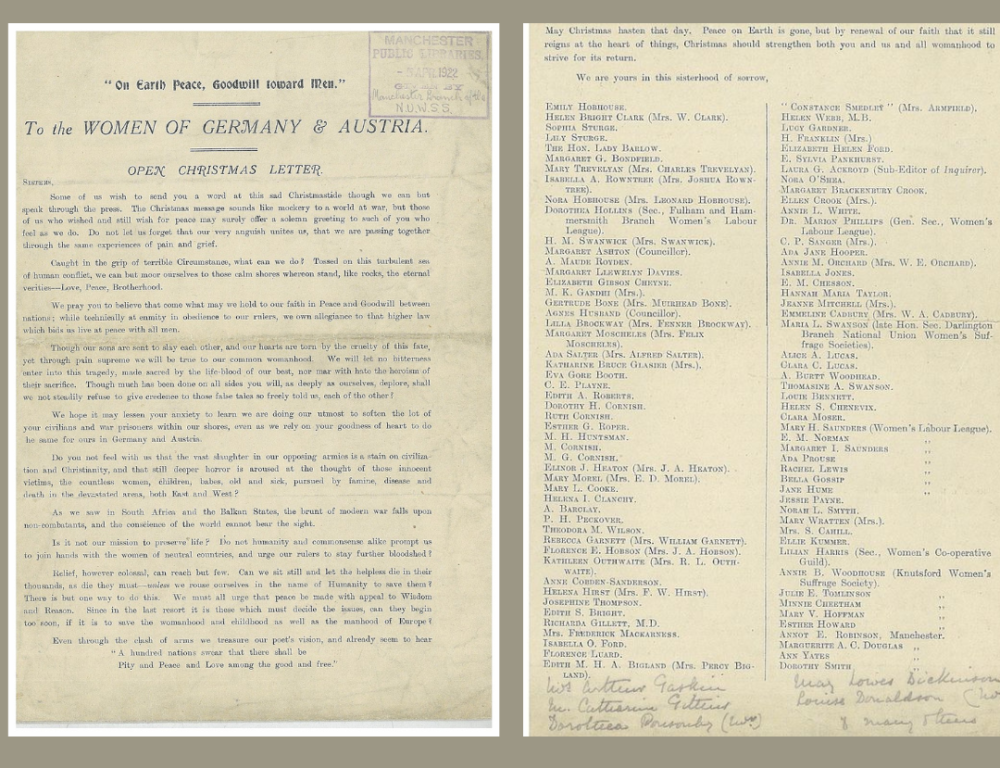

During the early years of the Great War, Miss Hobhouse penned a letter to express her sentiment about the egregious impact of the war on women. This letter eventually became known as the Christmas Letter of Peace, addressed to our sisters in Germany and Austria. The letter decried the war, encouraging peace and unity. [20] The feelings expressed were shared by many women, such as myself, who signed the letter under the stirring words “We are yours in this sisterhood of sorrow”. How true this would increasingly become.[21] The letter was published in a number of publications including New Year’s Day 1915 when it was published with our names listed in the International Women’s Suffrage News ‘Jus Suffragii”. This being a publication that reported news from our sisters across the world [22]. As you could imagine it was a controversial document, even among women supporting suffrage. There were those who thought it unpatriotic and those who thought the war would advance the position of women filling positions vacated by men. [23]. There was discussion as to whether ‘Jus Suffragii’ should continue through the war years, however, there was strong support to continue our international reporting. [22]

We saw our war effort in Manchester as one of protecting the lives of babies. It was through this I met Miss Margaret Ashton,[24] another strong woman committed to the cause.[25] I recall it was 1915, I had been appointed Doctor in Charge of Midwives and Miss Ashton approached me to see what could be done to advance the health of babies. There was a high mortality rate exacerbated by mothers who were already poor and had been left without support while their men were away at war. As a woman active in the cause, Miss Ashton explained she had already rallied support from the local women’s suffragist organisation, and they would aid in the establishment of centres around Manchester. The centres provided eligible mothers with regular meals, and if needed milk for babies. I had the difficult task of forming a criterion for eligibility for those women in the most need; heartbreaking when there were so many women in dire need.[15] The program was so successful it was used as an example for other parts of England.

There were amusing and jolly times during those Manchester years. I well remember when I obliged the request to judge a baby show. Oh, do not be shocked it was not appearance we were judging but health and nutrition. Imagine that day; a small room with six doctors including myself and 96 babies, each with their proud and anxious mothers scrutinising our every move. As you would suspect I do not usually hold with such contests, but this was to support an admirable local program, the Manchester School for Mothers. An excellent initiative training visitors to provide advice on healthy baby care to mothers living in the poorest parts of Manchester.[27] What an exhausting day; we weighed and assessed every one of those babies but such fun was had. All for a splendid cause.

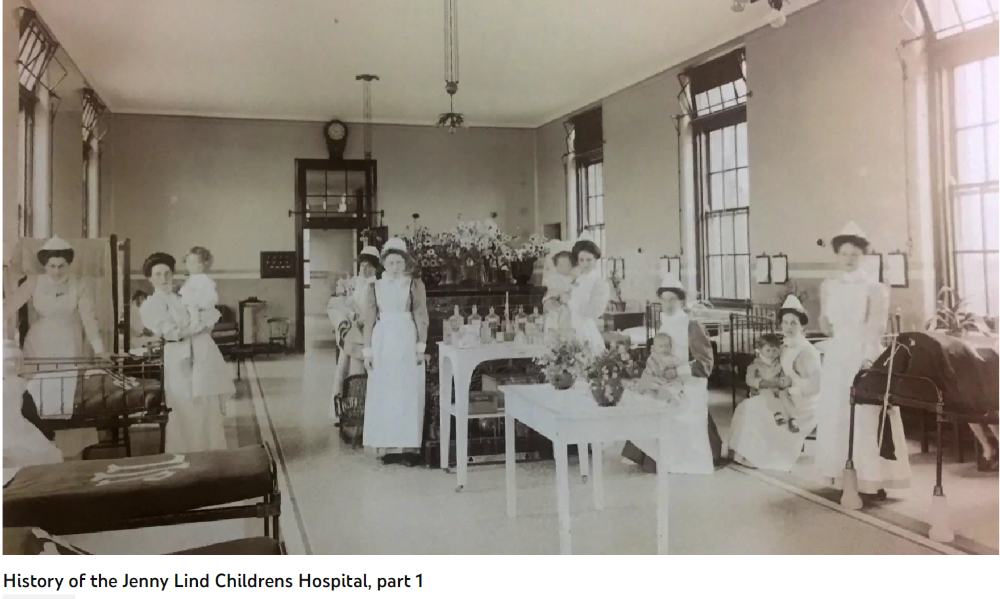

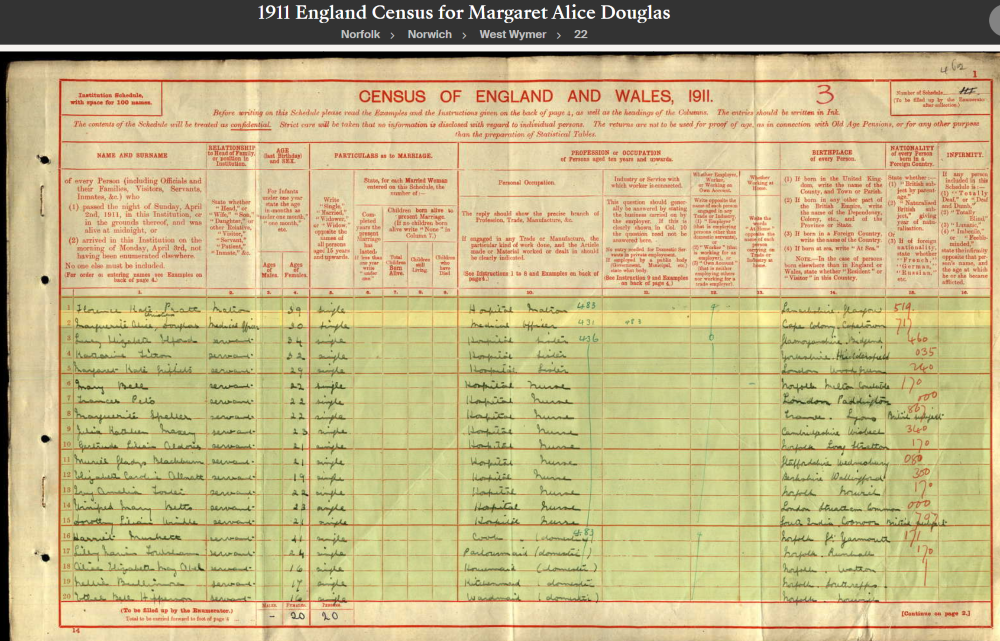

I have been talking much about women’s suffrage, yet it was not all about the cause. I took great satisfaction in my work as a doctor. One of my earliest positions was serving as a medical officer at the new Jenny Lind Infirmary in Norwich or ‘The Jenny’ as we affectionately called it. As a new graduate imagine my excitement and trepidation in acquiring such a position.[28]

I held the role of sole medical officer residing at the hospital. Thankfully, this position was deemed unsuitable for a male doctor, which worked in my favour. A decision I suspect was made because the only other individuals living in the hospital were women, namely Matron Pratt and the nurses.

Matron Pratt. Well, let it be said that at first I was in awe, and more than a little terrified of Matron Pratt. While only a few years older than myself, Matron Pratt had a vast amount of experience working with sick children.[30] Her stern but fair demeanour could be daunting, to say the least, yet the nurses and children in her care respected her. Those nurses hailed from across Britain. Why during my tenure, we even had a young woman from India. The requirement was that a nurse must be literate as this greatly aided in the treatment of the children under our care. Did I explain that while most children came from Norwich (though occasionally they came from other parts of Britain), the parents had to have a letter of recommendation for their child to be admitted. This of course meant this was not a hospital for treating the poor, unlike the Hospice Dr Inglis established in Edinburgh.[31] [29]

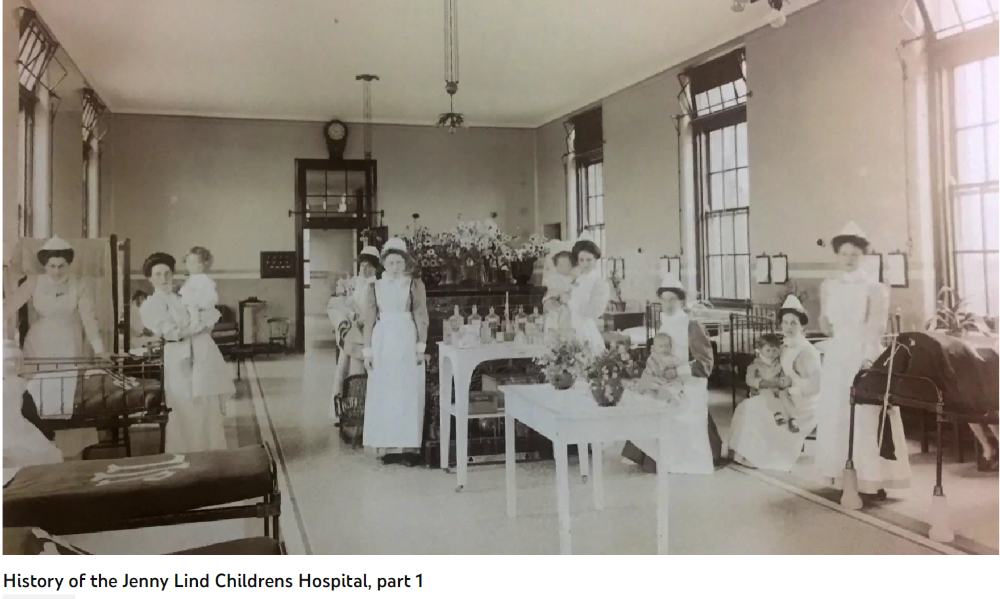

On my first day, I remember standing at the carved wooden gate with my gloved hand on the brass latch looking along the path to the entrance. Despite my heart pitter-pattering rapidly, my hands trembling and butterflies in the stomach, I was eager to begin. I had read so much about this hospital, built for the sole purpose of caring for sick children. The Jenny was widely known for its modern equipment and new approaches. Even the building was designed and decorated for the benefit of the sick children – from the outside, you could almost imagine a fairy tale castle with all the turrets and chimneys set off by the white striped brick trim and tuckpointing. Inside the large windows in the wards let in much light, the usual myriad of pipes gurgling and bubbling their way around the hospital were hidden from view, and the wards were filled with warmth, colour, flowers and toys. [29]

That first day I dressed with great thought. Remembering what we had been taught throughout college – that we must dress becomingly, and our behaviour must be exemplary.[3] While fashion was changing and skirts were beginning to be worn shorter – above the ankles – I wore mine of a suitable longer length and of sombre colour. I had my cream lawn pleated blouse with a modest high neck, firmly tucked into the nipped-in waist of my skirt. This was completed by a longer style, shaped jacket. It appeared seemly to wear a hat at least until I commenced work, which suited me because the broad-brim hat hid much of my hair that I had carefully coiffed and pinned to ensure it would remain out of the way once I began my work for the day. Before long I would think about the new fashion of short hair but that, along with wearing breeches was still seen as unseemly at that time. [33] And although boots were now becoming acceptable, I chose sensible court shoes. Such effort it took to show I was a lady doctor ready to be taken seriously,

Stepping into the ward my nerves began to settle as the familiar sights and smells drifted over me. The astringent smell of antiseptic. The rows of little beds and cots down each side of the room with the children in perfectly made beds, the counterpane corners tucked expertly and tightly under the mattress. Nurses gliding about in their full-length dress uniforms and starched white aprons with little caps set atop their perfectly coiffed hair. And all those sick children needing the skills I had worked under such duress to acquire, while some of those nurses would still see me as lesser than the male Doctors who attended, I no longer had to make the tiresome effort to prove oneself to fellow male students. And with that, I commenced my career in medicine.

Now in the early years of 1930s, our struggle for suffrage has been successful, memories of the great war fade, and slowly more women enter medicine. Through it all I have been privileged to thus far enjoy a career full of challenge.

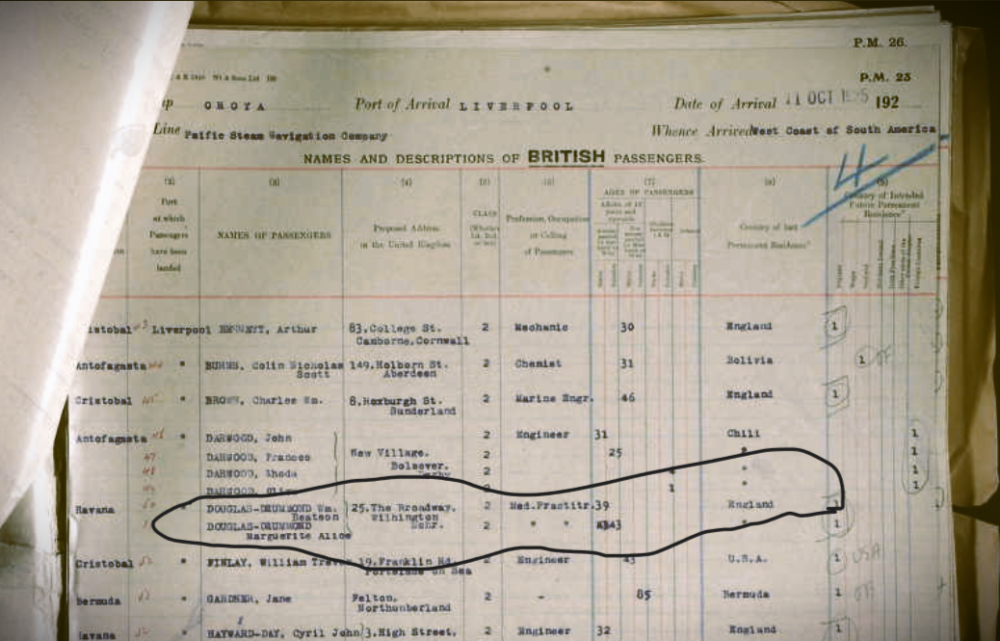

I have also been able to explore other lands including a memorable voyage to Havana in Cuba.[34] Not to forget that I met and married my husband, Bill, (Doctor William Beatson Drummond), during the early years of the war, and we have been able to work and travel together. A modern man Dr Drummond legally changed his name to include my own. We are now both Dr Douglas Drummond. [35]

I mentioned earlier the struggle it was to depart Cape Town in my formative years, yet I have revisited for leisure over the years. Now, I return to dwell permanently. How eagerly I am anticipating my return to the city of my birth. Oh, you should see my homeland – the skies forming a vast blanket of blue stretching infinitely above you, casting a white light that washes over the landscape. The brilliant shades of red and vibrant orange emanating from the horizon at sunset. Here I become almost poetic, yet it is difficult to fully describe the exotic nature and beauty of South Africa to one who has never been. It is Cape Town to which I now return and likely forever remain.

TIMELINE DR MARGUERITE ALICE CHRISTIAN DOUGLAS

REFERENCES AND BIBLIOGRAPHY

[1] ‘United Kingdom, Outgoing Passenger Lists, 1890-1960’, Family Search, Oct. 28, 2021. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:68PW-FRB4

[2] unsigned, English: Postcard entitled R. M. S. ‘Armadale Castle’ 12973 Tons. 1904. Accessed: Aug. 18, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:RMS_Armadale_Castle.png

[3] Edinburgh Evening News 20 July 1905, ‘Royal College of Physicians 1905’, The British Newspaper Archive | findmypast.com.au, 1905. https://search.findmypast.com.au/bna/viewarticle?id=BL/0000452/19050720/039&stringtohighlight=marguerite%20douglas (accessed May 16, 2023).

[4] J. M. E. Kirwan, ‘A Brief History of Women Doctors in the British Empire’, S Y N A P S I S, Dec. 17, 2017. https://medicalhealthhumanities.com/2017/12/17/a-brief-history-on-women-doctors-in-the-british-empire/ (accessed Apr. 25, 2023).

[5] The British Newspaper Archive, findmypast.com.au, ‘The Scotsman 1908 Medical Examination Passes’, Findmypast.com.au. https://search.findmypast.com.au/bna/viewarticle?id=BL/0000540/19081021/073&stringtohighlight=marguerite%20alice%20christian%20douglas (accessed May 17, 2023).

[6] N. R. of S. W. Team, ‘Malicious Mischief, Womens Suffrage in Scotland’, National Records of Scotland, May 31, 2013. https://www.nrscotland.gov.uk/research/learning/features/malicious-mischief-womens-suffrage-in-scotland (accessed May 16, 2023).

[7] H. L. Smith, The British Women’s Suffrage Campaign 1866-1928: Revised 2nd Edition. Routledge, 2014.

[8] Edinburgh medical journal. Edinburgh Oliver and Boyd [etc.], 1908. Accessed: Feb. 04, 2023. [Online]. Available: http://archive.org/details/nsedinburghmedical01edinuoft

[9] Balfour Lady Francis, Elsie Inglis. 1918. Accessed: Aug. 13, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Elsie_Inglis.jpg

[10] daisy, ‘Elsie Inglis’, Mar. 08, 2017. https://www.rcpe.ac.uk/heritage/college-history/elsie-inglis (accessed May 04, 2023).

[11] L. Inglis, ‘Elsie Inglis, the suffragette physician’, The Lancet, vol. 384, no. 9955, pp. 1664–1665, Nov. 2014, doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62022-5.

[12] ‘Elsie Inglis’, Wikipedia. Jun. 09, 2023. Accessed: Aug. 03, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Elsie_Inglis&oldid=1159267071

[13] ‘Looking Back: Elsie Inglis’. https://www.lifeandwork.org/features/looking-back-elsie-inglis (accessed Aug. 03, 2023).

[14] Manchester Evening News 3 March 1915, ‘A Profession Which Gains from the War’, The British Newspaper Archive | findmypast.com.au. https://search.findmypast.com.au/bna/viewarticle?id=BL/0000272/19150303/072&stringtohighlight=marguerite%20douglas (accessed May 16, 2023).

[15] Norfolk News, ‘Women’s Suffrage Debate’, Findmypast.com.au, May 07, 1910. https://search.findmypast.com.au/bna/viewarticle?id=BL/0000247/19100507/034&stringtohighlight=dr%20mary%20bell%20suffrage,%20dr%20douglas (accessed Aug. 03, 2023).

[16] Ada Nield CHEW, ‘Womanly Work Life Saving in Manchester’, Feb. 19, 1915. https://search.findmypast.com.au/bna/viewarticle?id=BL/0002227/19150219/042&stringtohighlight=dr%20douglas%20manchester (accessed May 04, 2023).

[17] C. Twinch, The Norwich Book of Days. The History Press, 2012.

[18] ‘Margaret Ashton’, Wikipedia. Jul. 22, 2023. Accessed: Aug. 04, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Margaret_Ashton&oldid=1166507037

[19] ‘Collection: Archive of Emily Hobhouse | Bodleian Archives & Manuscripts’. https://archives.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/repositories/2/resources/2830 (accessed Aug. 04, 2023).

[20] ‘Emily Hobhouse (1860–1926)’, Bodleian Treasures: Sappho to Suffrage. https://treasures.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/treasures/emily-hobhouse/ (accessed May 04, 2023).

[21] O. E. H. released: in 2013 by the M. Archives, English: Page one of the Open Christmas Letter sent by 101 British women suffragists ‘To the Women of Germany and Austria’ in December 1914. 1914. Accessed: Apr. 21, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Open_Christmas_letter_from_the_Suffragettes_of_Manchester,_page_1_(11350583266).jpg

[22] Labour Leader 24 December 1914, ‘British Women to the Women of Germany and Austria’, The British Newspaper Archive | findmypast.com.au, 1914. https://search.findmypast.com.au/bna/viewarticle?id=BL/0002734/19141224/036&stringtohighlight=marguerite%20douglas (accessed May 16, 2023).

[23] International Woman Suffrage News, ‘Jus Suffraggii’, The British Newspaper Archive | findmypast.com.au, Jan. 01, 1915. https://search.findmypast.com.au/bna/viewarticle?id=BL/0002218/19150101/040&stringtohighlight=marguerite%20douglas (accessed May 16, 2023).

[24] ‘Open Christmas Letter’, Wikipedia. Jan. 23, 2023. Accessed: May 04, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Open_Christmas_Letter&oldid=1135290942

[25] ‘Margaret Ashton · Mapping Women’s Suffrage’. https://map.mappingwomenssuffrage.org.uk/items/show/245 (accessed Aug. 03, 2023).

[26] WHN, ‘Serendipity in the Archives – Finding something when least expected!’, Women’s History Network, Aug. 16, 2015. https://womenshistorynetwork.org/serendipity-in-the-archives-finding-something-when-least-expected/ (accessed Apr. 21, 2023).

[27] Manchester Central Library: GB127.M50/1/8/1., ‘International Women’s Day: Margaret Ashton – Champion of Peace’, GMStories, Mar. 08, 2015. https://gmstories.org/2015/03/08/international-womens-day-margaret-ashton-champion-of-peace/ (accessed Aug. 13, 2023).

[28] ‘Flowers and Babies’, Manchester Courier, p. 10, Aug. 11, 1913.

[29] Ancestry.com, ‘Census 1911 Norwich’. Census Returns of England and Wales, 1911/i. Kew, Surrey, England: The National Archives of the UK (TNA) Series RG14, 1911, 1911. Accessed: Aug. 02, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.ancestry.com.au/imageviewer/collections/2352/images/rg14_11311_0923_16?pId=53819376

[30] ‘Podcasts about history of the Jenny Lind Children’s Hospital Norfolk and Norwich University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust »’. https://www.nnuh.nhs.uk/about-us/250th-anniversary-of-nn-hospital/our-250-year-history/jenny-lind-childrens-hospital/ (accessed Apr. 21, 2023).

[31] Ancestry.com, ‘Census 1901 Florence K Pratt’. [Online]. Available: https://www.ancestry.com.au/sharing/5415052?mark=7b22746f6b656e223a222f49553670535059456e763363745a5856327164714d334c586f3948695a3251694669676d62386c4433413d222c22746f6b656e5f76657273696f6e223a225632227d

[32] J. Styles, ‘The Rise and Fall of the Spinning Jenny: Domestic Mechanisation in Eighteenth-Century Cotton Spinning’, Text. Hist., vol. 51, no. 2, pp. 195–236, Jul. 2020, doi: 10.1080/00404969.2020.1812472.

[33] History of the Jenny Lind Childrens Hospital, part 1, (Mar. 30, 2022). Accessed: Apr. 18, 2023. [Online Video]. Available: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TsZpcorLRIU

[34] B. BROOKES, ‘A Corresponding Community: Dr Agnes Bennett and her Friends from the Edinburgh Medical College for Women of the 1890s’, Med. Hist., vol. 52, no. 2, pp. 237–256, Apr. 2008.

[35] ‘Passenger Lists Leaving Britain Havana’. Ancestry.com.au, 1926. Accessed: Aug. 03, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.ancestry.com.au/imageviewer/collections/2997/images/40610_B001084-00309?pId=39979863