Family History, The Tohunga Suppression Act and Learning in Unlikely Places

I would like to acknowledge that my ancestors were immigrants to Aotearoa New Zealand, in the mid-nineteenth century. I left this country in the late twentieth century and returned recently with a desire to learn more about my ancestors and the country I still consider home. This story follows the ongoing learning I have been undertaking about my ancestors, myself, and tangata whenua – people of this land.[1] Given this new beginning, I welcome any knowledge, education, and discussion to expand my knowledge and understanding. Melanie Atkins 2021

This story began for me early in 2021with a jolt of information on a large computer screen in a museum, of which the headline read: “Tohunga Suppression Act 1907”. [2] For the Indigenous Māori of Aotearoa New Zealand, this story began centuries before.

The harbour that began this story for the local tangata whenua and me stretches out before the museum within which I now stand. Here on the wild west coast of northern Aotearoa New Zealand with stormy cloud-filled skies, ferocious roiling seas, and wind-whipped swirling black sand. The coast is interrupted by a narrow, almost hidden entrance into Hokianga Harbour. For longer than histories have been told, three waveforms guard the entrance, concealing and protecting it from all but the most courageous of voyagers. Yet once inside, the harbour calmly meanders between land and dunes, almost river-like. Hokianga Harbour is prominent in Māori history.

Tangata Whenua say the legendary Māori navigator, Kupe, arrived here about 1,000 years ago with his whānau (family is a simplified meaning)[3]hapū (clan, a simplified meaning)[4] and crew in two huge waka (canoes). It is believed Kupe was the first to discover Aotearoa. After navigating his way across the seas, through violent storms and past the treacherous triple band of waves he brought his people safely to their new home within this harbour.

Kupe, the waka, and those that came on that journey are all part of the whakapapa[1] (genealogy) of many local iwi (people/nation).[4] The stories have been passed down through many generations. In the 21st century, Manea Footprints of Kupe is a new guided experience that brings knowledge to visitors through local iwi sharing traditional oral storytelling and an immersive 4D technology.

After exploring the life of Kupe, the museum teaches about the generations that followed. It leads on to explore the arrival of Pākehā[5] (simplified meaning ‘early Europeans’), the subsequent decimation of Māori culture, beliefs, and language, and the increasing rebirth of Māori language and culture since the 1970s. The destruction of culture became starkly clear to me as I learned more about the impact the arrival of the Pākehā had, such as banning the practice of the Tohunga.

The screen in front of me described the role of the Tohunga: a skilled and learned person, a guide, an expert, chosen and trained in a specific field because they show natural talent. The Tohunga might be expert in areas such as carving, navigation, healing, spiritual guidance, artists, genealogy. [6] I was taught in school in the 1960s that the Tohunga was a ‘medicine man’, I now understand the role is significantly more skilled and extensive than what I had learnt all those years ago.

I have learnt that Tohunga are integral in Māori culture, “an intimate part of Māori life”[7]. In a culture where spirituality is central, Tohunga are the link between the spirit world and the physical world. Tohunga ensure that māoritanga (culture and beliefs) and tikanga (customs) are followed for the benefit of all. They advise, guide and protect the rituals within their area of expertise. Crucial to this story is thatTohunga are central to māoritanga and are an integral part of the community.[6]

Pākehā generally viewed Tohunga through a narrow lens: that of healer, a view that the Tohunga Suppression Act 1907 reinforced. Descriptions of Māori at the time were that of ‘heathens’ and ‘dangerous savages’,[8] reinforcing the idea that Tohunga were dangerous, charlatans, particularly to church representatives who viewed the practice as witchcraft “a reversion to paganism”.[7]

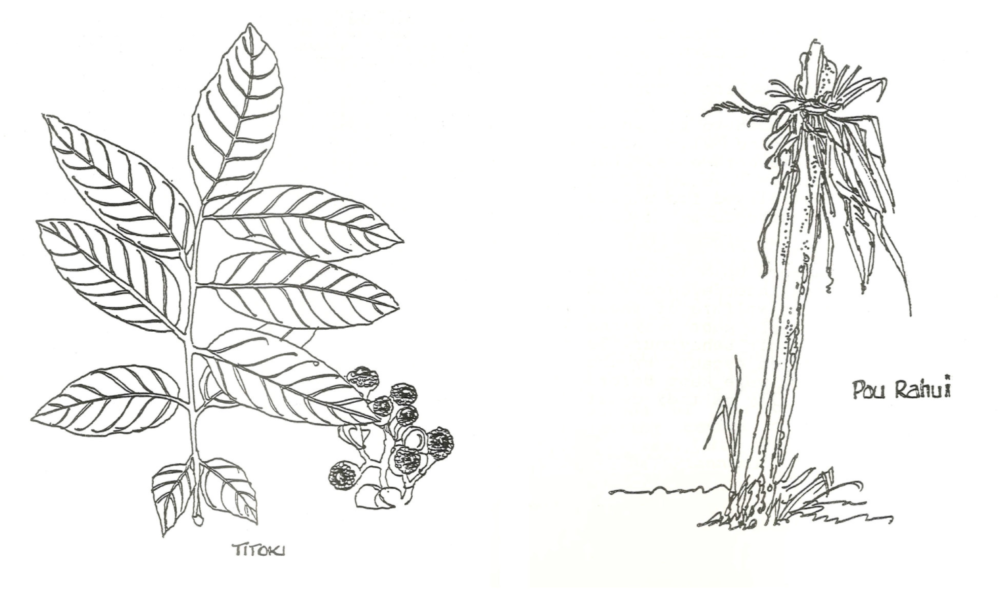

Rongoā Māori was and is the traditional and extensive healing system of Māori people. Knowledge of this holistic healing, which includes physical, spiritual, family, and herbal,are held by the Tohunga Rongoā. The skills and knowledge of Rongoā Māori passed orally through generations includes an understanding of anatomy, the ability to treat physical conditions, understanding plant-based remedies. Healing practices also include psychological and social support and rehabilitation[9] Many Pākehā did not understand the breadth of knowledge held by the Tohunga Rongoā.

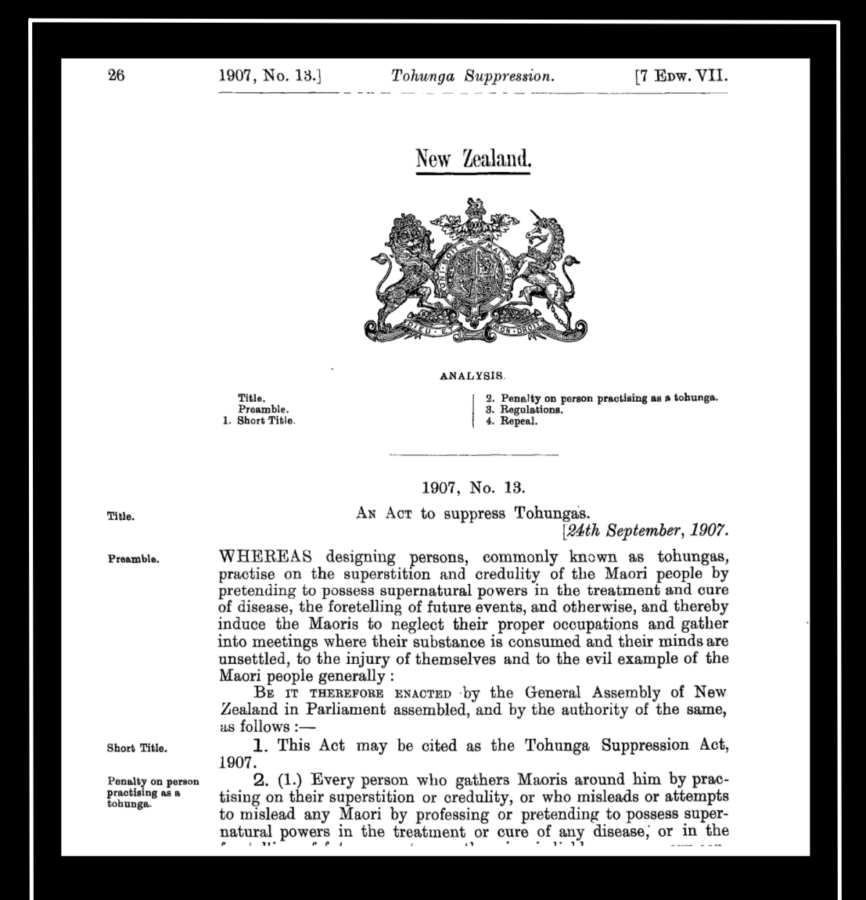

Imagine the shock of seeing that large museum display, “Tohunga Suppression Act 1907”.[2] Adding to the impact were images of the introductory passages of this one page Act. This was a New Zealand Government law banning the practice of Tohunga, a core part of Māori culture. There I was: curiosity piqued, indignation raised, questions popping.

Barely a page long, the Act outlawed “[every] person who is or pretends to be a tohunga [sic] or who gathers Māori’s around him by practising on their superstition or credulity, or who misleads or attempts to mislead”.[2]

How did this story intersect with my family history?

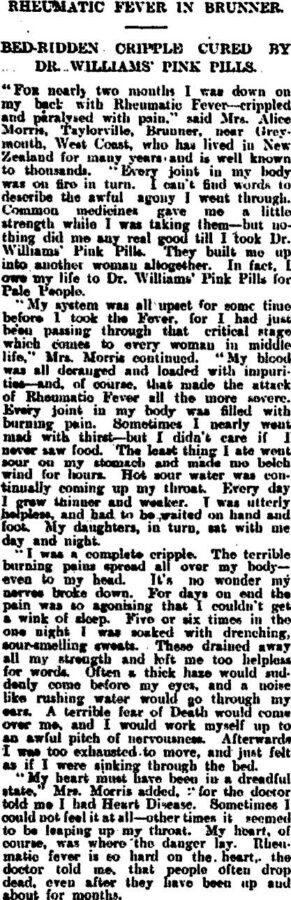

As I began my learning, I had not thought this history would intersect with my own family story. A newspaper clipping from family archives came to mind, the heading “Too Crippled to Walk” which promoted Dr William’s Pink Pills for Pale People.[10] This article, which we might now describe as an advertorial, was an interview with my ancestor: Alice Morris.

The article in the Brunner Times of December 1906 introduces Mrs Alice (Appoo) Morris who gives a lengthy and detailed description of her symptoms. Alice states that she had rheumatic fever when she was young and was now “crippled and paralysed with pain”.[10] She concluded by declaring that “[fifteen] boxes of Dr Williams Pink Pills saved my life”.[10]

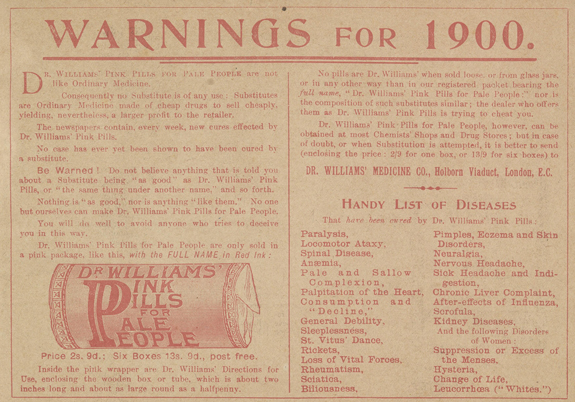

Boldly claiming an undisclosed ‘secret formula’ and sold through mail order worldwide, the advertisements for these pills contained a lengthy list of cures, all of which went unchallenged. A remedy for conditions such as “paralysis”, “palpations”, “anaemia”, and “all kinds of female weakness”.[11] One pamphlet even proclaimed the pills could cure consumption (tuberculosis). [5] An examination later found that the secret formula consisted solely of “iron oxide, magnesium sulphate (iron supplements), powdered liquorice, and sugar”.[13]

Why were Tohunga banned while Pākehā preparations such as those my ancestor recommended could flourish without censure? Was the Tohunga Suppression Act a visible, legislated response to prejudice and racism? Was it enacted by people who considered the public risk of Tohunga so significant that they would outlaw other people’s cultural and spiritual foundation? Was it brought about by the desire for power over others, the greed for a lush land? Or could it have been fear of a strong Indigenous peoples? ‘Yes’ I shouted to each of these questions. I discovered that relationships, attitudes and politics then, as now, were complex. Yet, tangata whenua were and continue to be disadvantaged by the history that began with the imposition of Pākehā culture and values, and taking the of their land.

What were the relationships and attitudes between Māori and Pākehā?

In the century preceding the proclamation of the Tohunga Suppression Act, people arrived in Aotearoa New Zealand from many nations across the world: England, Ireland, Scotland, France, Germany, America. The arrival of Pākehā was to have a devastating impact on Indigenous Māori people that continues today, including the loss of culture, land, life and health.

Despite this, from first arrival there were Pākehā who worked alongside Māori in a mutually respectful relationship. Māori and settlers working across both cultures, teaching and learning from each other.

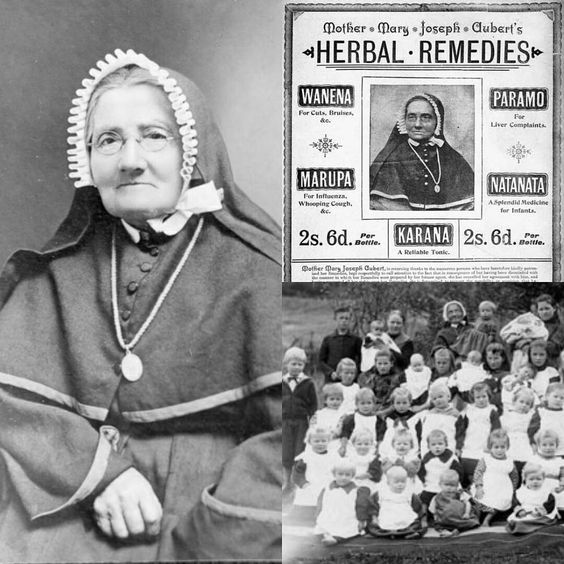

Suzanne Aubert came to mind. On a visit to Hiruharama (Jerusalem), I learned of Suzanne Aubert, who came to Aotearoa New Zealand as a Missionary.Sister Aubert had studied botany, chemistry and medicine, and worked as a Nurse in France.[14] While living in Aotearoa New Zealand, Sister Aubert, learned the Māori language and worked alongside Tohunga Rongoā to learn the properties of local plants and Māori herbal remedies. Combining this with her knowledge, Sister Aubert was able to make blended remedies for the benefit of both Māori and Pākehā.[15]

While some settlers worked alongside Māori, others, including government officials, viewed Māori as “inferior”[16], as a people who needed to be “civilised”[7]. Māori were viewed as a group of people not following (and not fitting) Christian beliefs of the time.[8] Rather than understanding the ancient culture, Pākehā treated Māori with fear and suspicion. Without working to understand a different culture, early Pākehā images and writings often depict Māori as dangerous, one describing “cunning, deceitful savages”.[8] Was this devaluing and dehumanising a convenient way to justify the acquisition of land and wealth?

How Did the Tohunga Suppression Act Come About?

The Tohunga Suppression Act was one in a range of legislated measures to control Māori and acquire land. In 1867 the Native Schools Act was passed, including a mandate that children only speak and learn English in schools. Māori language was often banned and children punished for speaking their language.[17] This decimated Māori language until changes began in the 1980s culminating in recognising Te Reo Māori as a national language of Aotearoa New Zealand alongside English and New Zealand Sign language.

It was a surprise to learn the Tohunga Suppression Act was introduced into parliament by James Carroll, a “Native Minister”[9] and Māori parliamentarian. Why would this be? Further reading revealed James Carroll alongside three other Māori members, and a group of Māori Medical Doctors, worked within the Pākehā government system. This group of academics was concerned with the increase of Tohunga who were not traditionally skilled and qualified. Further they supported western medicine and thus decided to take action.[9]

Before presenting the Act, James Carroll worked for several years to control unqualified Tohunga. He held concerns about the proliferation of unqualified Tohunga with the increasing destruction of Māori culture.

James Carroll and the group of Māori academics were also concerned that introduced diseases such as influenza, measles and whooping cough were far more virulent and devastating to Māori. In addition, they hoped the Act would encourage people to seek western medicine.[9]

At that time, Rongoā Māori weakened by the impact of Pākehā could not deal with these introduced diseases, neither could Western medicine. It would be centuries before Rongoā Māori would be reintroduced and accepted alongside western medicine.[18]

Unlike the Quackery Prevention Act,[19] which was to come later, the Tohunga Suppression Act, when introduced, was a complete ban on Tohunga practice, it did not differentiate between unqualified or expert Tohunga. The former would be a ban only on treatments seen as dubious. While there were few prosecutions under the Tohunga Suppression Act, it is thought to have contributed to the advancing loss of culture and way of life for the tangata whenua,[18] a people already denied their language, way of life, and land.

Later, it was found the Tohunga Suppression Act 1907 contravened the Te Tiriti (Treaty of) Waitangi signed between Māori and Pākehā in 1840. The banning of Rongoā Tohunga challenged Māori wisdom that was considered a “taonga” (treasured knowledge, art, object created by a person/s) whose protection was agreed through the Treaty.[18]

Why were Pākehā “cures” allowed to flourish?

A further discovery in my learning was that the introduction of the Tohunga Suppression Act highlighted dubious practices in Pākehā’ cures. Complaints about the lack of attention to “Pākehā quackery”[7] led to new legislation a year later, the aptly named ‘Quackery Prevention Act 1908“.[19]

As described earlier, the Quackery Prevention Act only banned rogue treatments while the Tohunga Suppression Act banned ‘rogue’ and legitimate Tohunga. This was not the only inequity between the Acts. The Quackery Prevention Act allowed the right to appeal, whereas the Tohunga Suppression Act did not. The Quackery Prevention Act lists heavier fines, but the Tohunga Suppression Act described a potential jail sentence.[7]

While the Tohunga Suppression Act had a far-reaching and devastating impact on Māori culture and health, the Quackery Prevention Act did not have the same impact on western medicine. This act did not even stop all quackery, the pink pill production proliferated. Bought by a large Canadian company, distribution of ‘Dr Williams Pink Pills’ continued to expand acoss 82 countries [21] assisted by enthusiastic supporters recording their miracle cures, like those of my ancestor Mrs Alice Morris.

What learning came from this?

What I learned that day on the Hokianga Harbour grew to become far more than a history lesson, more than a story connected with my family history. As I ranted at early Aotearoa New Zealand history of power and greed, I had no clue that shards of colonial thinking were still living within me. My first thought was to avoid stories that might expose this thinking, or I could continue learning and be open to feedback, experiences and stories. I have chosen the latter.

As with many stories about history, it reminded me that human actions and their consequences make up the stories of history. Those actions can have unforeseen consequences far into the future, sometimes with devastating effects. It also reminded me that human activity is rarely all good or evil. We benefit from a more profound and open-minded exploration of actions past and present, including our own. Family history and political actions both need to be understood within the context of their time, culture and our own lens to the past.

Exploring this story has been a wonderful reminder of how much more than names and dates family history can be.

END NOTES AND BIBLIOGRAPHY

The use of Te Reo Māori language.

Alongside English and NZ Sign language, Te Reo Māori is now the National language of Aoteoroa New Zealand. There are Māori terms in common usage throughout the country, even by those not fluent in Te Reo. English is the language I write in but I have used a number of Māori terms.

Secondly, translations are difficult because Māori terms often have deeper meanings than the simple English translation.

Whakapapa is a pertinent example, while the simple translation is ‘genealogy’, the Māori meaning is deeper and more connected to culture and land:

“Whakapapa … the actions of creating a foundation and layering and adding to that foundation … whakapapa allows people to locate themselves in the world, both figuratively and in relation to their human ancestors. It links them to ancestors whose dramas played out on the land and invested it with meaning. By recalling these events, people layer meaning and experience onto the land.” [6]

Finally, I note that while the terms Māori and Pākehā are commonly used, these are early European constructed terms and can be contentious[22]

I chose to use the commonly used words and terms central to the story. While my intent is to be respectful, if it is otherwise, please share this with me.

CITATIONS AND BIBLIOGRAPHY

[1] N. Z. M. for C. and H. T. M. t, ‘Whenua – the placenta’. https://teara.govt.nz/en/papatuanuku-the-land/page-4 (accessed Oct. 15, 2021).

[2] ‘Tohunga Suppression Act 1907 (7 EDW VII 1907 No 13)’. http://www.nzlii.org/nz/legis/hist_act/tsa19077ev1907n13353/ (accessed Oct. 15, 2021).

[3] N. Z. M. for C. and H. T. M. Taonga, ‘Contemporary understandings of whānau’. https://teara.govt.nz/en/whanau-Māori-and-family/page-1 (accessed Oct. 26, 2021).

[4] N. Z. M. for C. and H. T. M. Taonga, ‘The significance of iwi and hapū’. https://teara.govt.nz/en/tribal-organisation/page-1 (accessed Oct. 26, 2021).

[5] Karaitiana, ‘Origins of the term Pākehā’, Karaitiana Taiuru, Mar. 24, 2021. https://www.taiuru.Māori.nz/origins-of-the-term-Pākehā/ (accessed Nov. 11, 2021).

[6] ‘Manea – Footprints of Kupe Experience’, Manea, Aug. 28, 2019. https://maneafootprints.co.nz/ (accessed Oct. 27, 2021).

[7] R. Lange, May the People Live: A History of Māori Health Development 1900-1920. Auckland University Press, 1999.

[8] ‘“Cunning, deceitful savages”: 200 years of Māori bad press’, Stuff, Jun. 02, 2018. https://www.stuff.co.nz/life-style/103871652/cunning-deceitful-savages-200-years-of-mori-bad-press (accessed Oct. 16, 2021).

[9] ‘Demystifying Rongoā Māori Traditional Māori Healing’. Accessed: Oct. 15, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://bpac.org.nz/magazine/2008/may/docs/bpj13_Rongoā_pages_32-36_pf.pdf

[10] ‘Dr. Williams’ pink pills cure rheumatic fever, Brunner. | West Coast New Zealand History’. https://westcoast.recollect.co.nz/nodes/view/3647 (accessed Oct. 15, 2021).

[11] ‘Dr Williams’ “Pink Pills”, London, England, 1850-1920’, Wellcome Collection. https://wellcomecollection.org/works/wqk6xcj8 (accessed Oct. 16, 2021).

[12] ‘Dr Williams’s Pink Pills. for Pale People.’, Otago Witness, no. 2267, p. 20, Aug. 12, 1897.

[13] ‘Dr Williams’ Pink Pills for Pale People: TB Quackery in the 19th Century’, Brewminate: We’re Never Far from Where We Were, Jun. 26, 2020. https://brewminate.com/dr-williams-pink-pills-for-pale-people-tb-quackery-in-the-19th-century/ (accessed Oct. 15, 2021).

[14] ‘Aubert compassion.org.nz’, compassion.org.nz. https://compassion.org.nz (accessed Oct. 15, 2021).

[15] ‘Suzanne Aubert’. https://www.suzanneaubert.co.nz/ (accessed Nov. 11, 2021).

[16] N. Z. M. for C. and H. T. M. Taonga, ‘European ideas about Māori’. https://teara.govt.nz/en/european-ideas-about-Māori (accessed Nov. 19, 2021).

[17] N. Z. M. for C. and H. T. M. Taonga, ‘The native schools system, 1867 to 1969’. https://teara.govt.nz/en/Māori-education-matauranga/page-3 (accessed Oct. 27, 2021).

[18] KO Aotearoa tenei: a report into claims concerning New Zealand law and policy affecting Māori culture and identity. Wellington: Legislation Direct, 2011.

[19] ‘Quackery Prevention Act 1908 (8 EDW VII 1908 No 247)’. http://www.nzlii.org/nz/legis/hist_act/qpa19088ev1908n247335/ (accessed Oct. 15, 2021).

[20] ‘Kevin D. Lo, Carla Houkamau. Exploring the Cultural Origins of Differences in Time Orientation between European New Zealanders and Māori. NZJHRM. 2012 Spring. 12(3),105-123.’ Accessed: Nov. 11, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://repository.usfca.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1009&context=olc

[21] ‘5 crazy cures sold by con artists – Dr. Williams’ Pink Pills for Pale People’, The Vintage News, Jun. 07, 2016. https://www.thevintagenews.com/2016/06/07/bizarre-vintage-cures-sold-cons/ (accessed Oct. 15, 2021).

[22] ‘What’s in a name? How “Pākehā” became corrupted’, Stuff, May 08, 2019. https://www.stuff.co.nz/life-style/life/112533002/whats-in-a-name-how-pkeh-became-corrupted (accessed Nov. 11, 2021).