Julia

Streaming sunlight illuminates the likeness of a young woman, the deep muted colours of the portrait enhanced by the gold-trimmed frame. The image shows a woman with pale, delicate features looking out past the side of the camera frame. Her exquisite face is forever captured in the tinted sepia portrait. For four generations this portrait of Euphemia Julia Appoo has hung in the homes of her descendants. A picture of resilience and fragility, of Victorian womanhood, belying the strength needed for the harsh conditions of her life. This is my great great grandmother, known to her modern descendants as Julia.

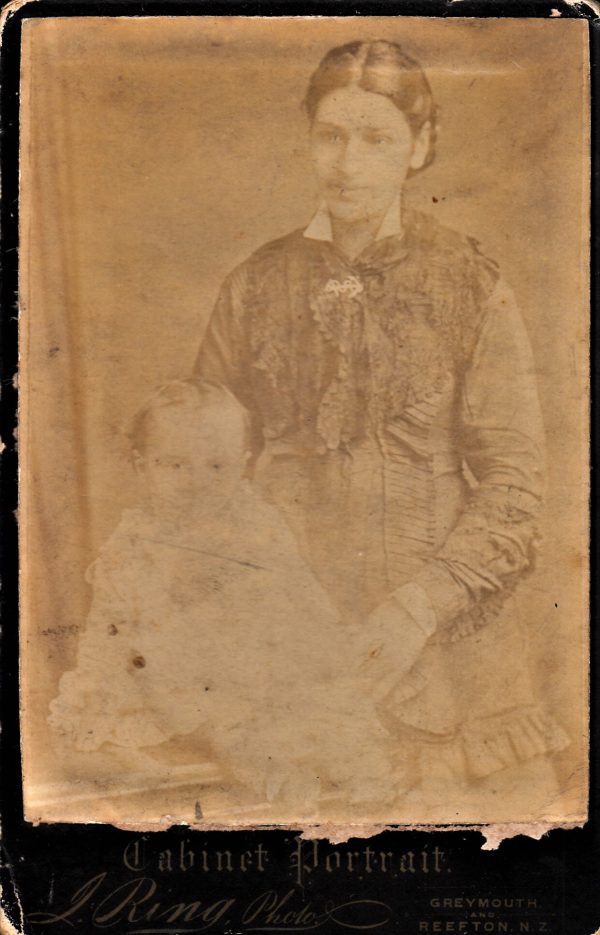

The portrait was shared throughout the family for many years. Some had a copy in sepia tones, some in tinted colour, some in black and white, all variations of the same image. When setting out to discover more about the life of the woman in the portrait, I was given a faded photograph showing the same young woman. In this image, Julia is standing stiffly, dressed in an ornate Victorian gown, tight over a curved belly with a toddler seated in front of her. The toddler is now barely visible, the outline of a face and a light-coloured, over-frilled, flounced outfit. Looking at this full image, the innocent beauty and romance of the woman in the portrait collides with the reality of her life.

Julia’s story is reflective of many pioneer women, particularly living in remote locations. Resilience, stamina and self-reliance were essential qualities for 19th-century pioneer women. For Julia, there was the added hardship of bearing six children in ten years whilst living with a terminal illness. Like many women, particularly those who could not write, little of her story remains. The slim records show that she married in 1881 and had six children over the ensuing ten years. Julia died in 1892 of Phthisis (now known as Tuberculosis) and Congestive Heart Failure.

For many women, their lives are recorded as an addendum to men’s and unsurprisingly I discovered much of Julia’s story through researching the men in her life. After a short life, spent as a seaman travelling the globe and later following the thrill of gold-seeking, Julia’s father, John Jacobus Appoo, died a few months before Julia was born. Phthisis also caused his death. After an early childhood spent on the goldfields of Victoria, Australia, six-year-old Julia emigrated to New Zealand with her family. Her stepfather, a coal miner from Newcastle on Tyne, England, brought the family to a remote coal-mining town on the West coast of the South Island of Aotearoa New Zealand. In the raw and rugged Taylorville, a tiny place built for the Brunner coal mining families, Julia lived out the rest of her life.

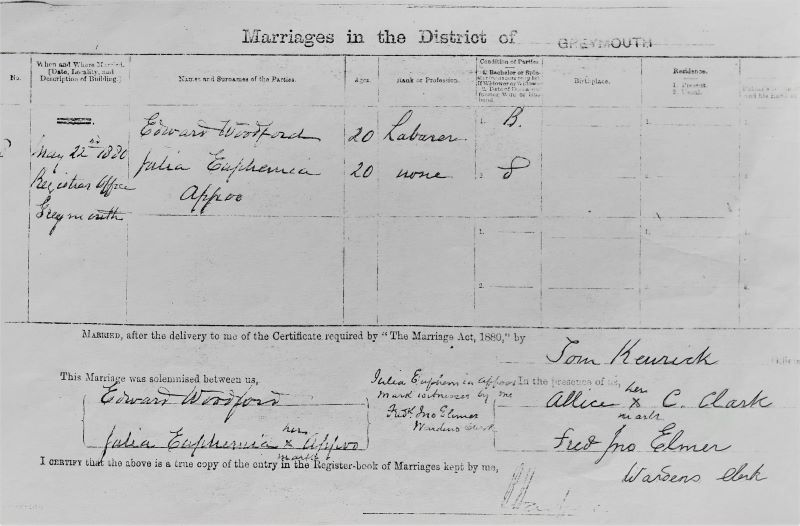

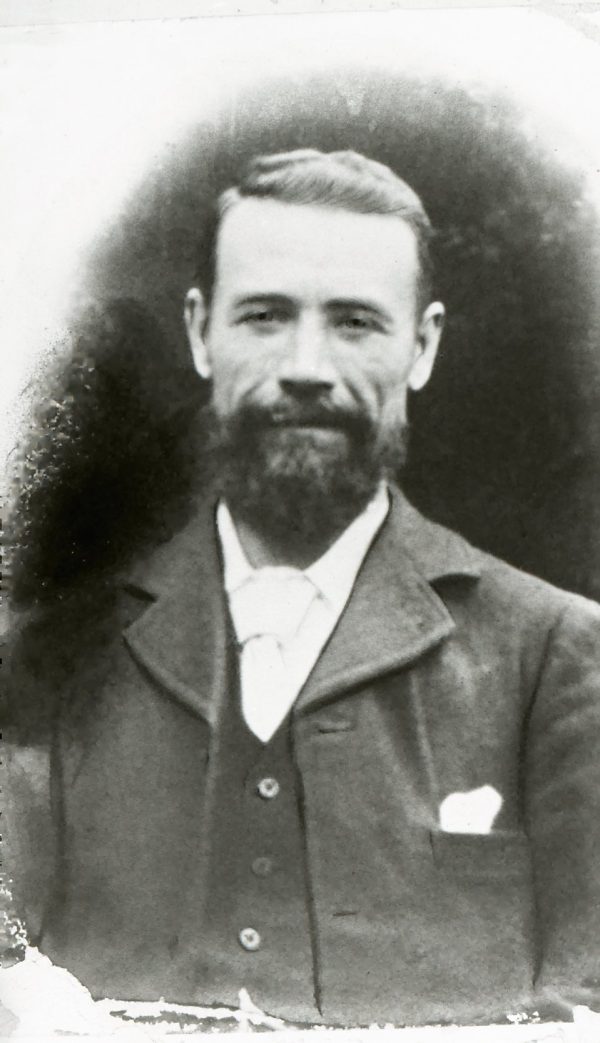

No clue has been found as to how Julia met a labourer who had newly arrived from Oxford, England. It is known that on Saturday the 22nd of May 1880, on an autumnal West Coast day, the fragile, delicately featured 21-year-old Euphemia Julia Appoo, married the bearded, handsome 21-year-old Edward Spencer Woodford in the Greymouth Registry Office. Julia’s mother, Alice, witnessed the marriage[1]. Both Alice and Julia signed their names with an X. It was not uncommon at that time for women to be unable to write. Edward signed his full name.

The local Grey Argus newspaper reveals that the Monday following their marriage was a holiday celebrating Queen Victoria’s Birthday. A large parade was planned for Greymouth, and it was reported there was “every prospect of the weather … being fine”[2]. Hopefully Edward and Julia not only had fine weather on their wedding day but were able to enjoy the Queen’s Birthday celebrations in Greymouth before returning to Taylorville. It seems extraordinary that there was no mention of marriages or births of the day in the newspaper, yet it is reported a young boy broke his wrist while playing in the school Gymnasium[2]. The cost of 5 shillings to advertise a marriage was likely prohibitive.[3]

Julia and Edward began their married life in Taylorville. Julia was already familiar with the damp, misty coal mining town high above Greymouth. A more recent arrival, Edward was probably less used to the weather and the isolation of the town.

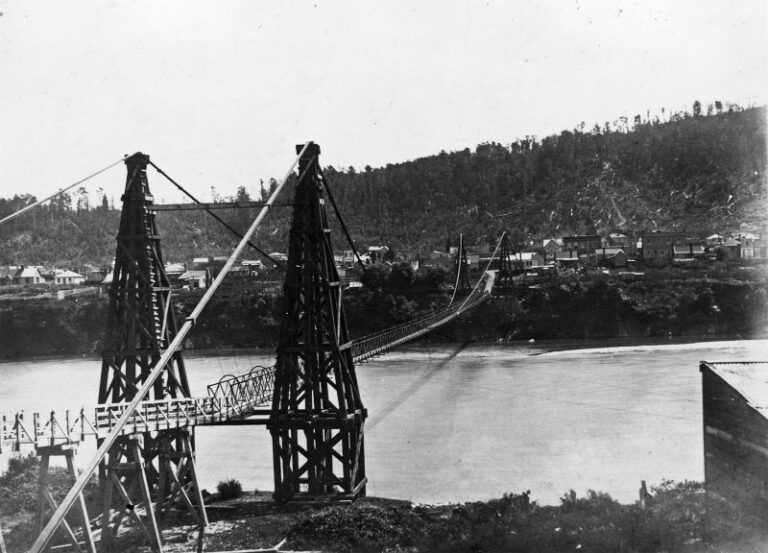

Edward worked as a labourer in Wallsend across the roaring Grey River from Taylorville. While directly opposite Taylorville, the men had to walk to the Brunner bridge in the adjacent town to make the crossing[4]. In 1888, the Wallsend Taylorville bridge was built. This perilous, narrow, pedestrian swing bridge would have enabled Edward to get to and from work more quickly, though perhaps not without trepidation. Crossing the bridge was a fear-filled experience for some.[5]

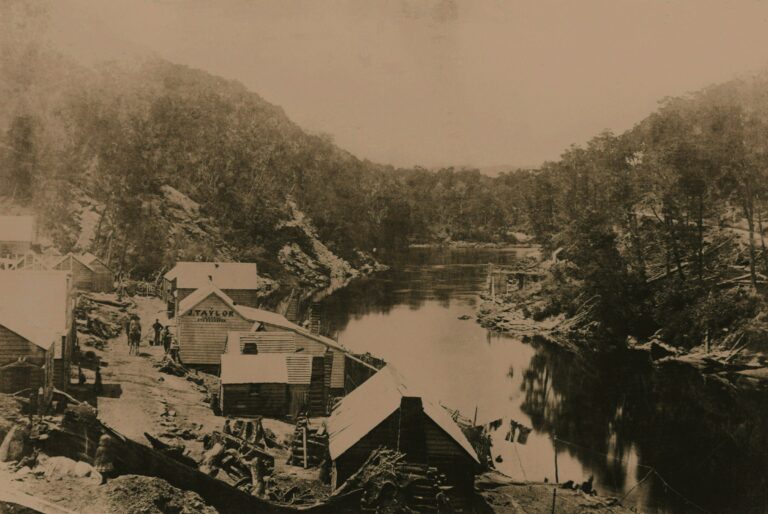

Taylorville was a tiny but growing town, rows of small and simple wooden houses clutching the riverside, with lines of similar houses hugging the hillside on the other side of the rough dirt track that formed the area’s main road. The town’s namesake, Mr Taylor’s General Store, sat boldly on the river’s edge in the centre of town. The store owner was well known to all, as he had sold the land to Brunner Mine, enabling them to build this little mining community for the growing number of coal miners and their families. After his death, his wife would donate land for the first school in Taylorville.[6]

In 2021, I stood in the outdoor carriage of a train as it sped through the mountain spine separating the South Island’s East Coast from the bleaker, wilder West Coast. I was keeping watch of the land of my ancestors. It was early afternoon as we reached Taylorville, and already the mountains were dressed in heavy mist. Along the rail lines, coal slag heaps dominated. Beyond the black man-made mountains ran the ferocious blue-black Grey River, pounding the final ten kilometres to the end of the line for river and rail in Greymouth.

In the 1800s it could only have been a rugged life in this town. The surroundings were daunting; thick dark bush, towering native trees spearing through the canopy, green and silver ferns fanning across the landscape and huge twisting vines filling whatever space was left. Roughly cleared but encroaching into the town wherever it could, the bush seemed to push the tiny town into the pounding river. The small one and two-roomed roughhewn wooden houses with wooden tile rooves sat side by side with little space for a garden. Only the most determined hacked, carved, and tended a plot out of the unforgiving bush.[7].This was home for most of Julia’s life.

Taylorville was created around 1875 as miners and their families arrived to work in the nearby Brunner mine, spilling out from the town of Brunnerton. Julia and her family had lived in the nearby town of Brunnerton on first arriving from Australia in 1867. Not only had her father died just a few months before she was born, her stepfather went missing and was killed in a mining accident two years after they arrived in New Zealand. [8]

After her husband’s mining accident in 1869, Julia’s mother, Alice, remained in the area for the rest of her life. Newspaper items reflect a life of continuing poverty, including requests for rate relief.[9] Julia and her sister, Alice Elizabeth, also remained in Taylorville; their three half-sisters and brother moved away and settled in other parts of the country.

Then, as now, the isolation of coastal and mining communities in the area built the ‘West Coaster’ reputation: self-sufficient, resilient, straight-talking and strongly community-minded. Up in the hills sitting on the banks of the Grey River, Taylorville was even more remote and self-contained than the coastal towns of those early times.

As I push a button or two to set the washing machine in action, turn knobs to provide heat through the house, flick a switch to create light, and turn a tap to procure hot or cold running water, it is difficult to imagine a typical day in Taylorville in the closing decades of the 19th century. The comparison renders unimaginable the thoughts of how a young woman with an increasing number of children and diminishing health managed day to day and year by year with no such conveniences. Adapting from women’s history recorded in the region I visualise what daily life for Julia might be like.

Wash day, Julia thought with dread, waking and arising early before her husband. Sleepless and breathless, she left the bed and stoked the kitchen fire. The smoky start to the morning aggravated her already overworked lungs causing a coughing spasm. Waiting for it to pass, Julia then swung the rod over the fire with a large pot filled with water to boil and began the porridge for breakfast.

The fire must be kept going to cook meals and heat water all day, and through all weather. Whatever season, Julia contends with the smokey layer inside the house combining with the weather oozing in through cracks in the walls. It is a reluctant task in summer, particularly in the oppressive humid December heat.

“What do I prefer?” she wondered as she stoked the fire and gazed out across the river, “the icy cold wet and damp of winter that soaks my bones, or this hot sticky summer heat that leaves one gasping for air?”

“ It is an unforgiving place,” she thought, shuddering at the memory of the native rats she heard boldly scratching around the house.

The bushfire threat in the hot summers, the river spilling its banks in late winter, after the snowmelt high above in the Alps. The change of seasons provides the only respite, Spring and Autumn bringing milder weather and clear blue-skied riverside days.

In the 1800s, necessity dictated that the women in such remote towns support each other, working together with little outside assistance. There was no doctor, nurse, midwife or undertaker, at least not within a day’s travel. The women tended the ill and wounded, assisted births, supported grieving families, and prepared bodies after death. Mining accidents were common and coffins took days to arrive from the coast. The first hospital on the West Coast was built in 1875, a small single block building accessed along a rutted dirt road in coastal Greymouth, commonly serving miners injured from accidents.[10]

The men and women of the West Coast, with ingenuity and inventiveness, created comforts and labour-saving devices, such as wooden troughs hollowed out for rising the bread dough, and camp ovens to bake bread. Flour sacks were washed and used for blankets, floor rugs, clothing, even beds when the bags were filled with plants such as ferns and tied between poles. It was likely Julia and Edward refashioned whatever they could to meet the needs of daily life[11]. This lead to my imagining an example of Edward’s ingenuity.

Edward had cut the top off an old kerosene tin and fashioned it into a washbowl. The container sits on a crudely fashioned stand and is filled with water boiled over the kitchen fire. First out of bed, Julia washes and dresses in the canvas lean-to outside the house, or by the fireside in winter. On bath day, this would take much longer. The log of wood Edward had hollowed out for a bath would be filled with hot water boiled over the outside fire. Often this bath would be shared by all family members, with Edward having the first bath.

The days Julia dreads most are laundry days. A large tin drum is filled with water and hung over the fire outside the hut. Some women in the town were lucky enough to have a copper tub treasured for this task. Once the water was boiling, the clothes had to be soaped, scrubbed, boiled, rinsed and hung to dry. An exhausting task at any time. Without the help of her mother, sister, or the women in the town, Julia does not know how she would manage.

A year after marrying Edward, Julia found herself about to give birth to her first child. At this time, attending births was women’s work. Edward would have been at work, or out of their tiny home. Undoubtedly if nearby, he along with others in the village, would have heard the sounds of childbirth through the thin walls and close quarters of the houses. I can only visualise Julia late in her first pregnancy.

It was a long December night in 1881 and Julia’s sleep was fitful. Her first child was due any day and rest was difficult. So heavily pregnant, it was impossible for Julia to find a comfortable position on the hard wooden slat bed. Trips to the outside privy were frequent, praying the giant native Weta insects were not lurking inside. Luckily, the nights had been cool and there was the beauty of the night sky. You could never be anything but wonderstruck looking up at the deep navy Southern sky, showered with millions of tiny sparkling stars comprising the swirling Milky Way. Julia did not know whether to wish the birth to come or for the baby to keep safely inside her for just a little longer.

In the late 1800s giving birth could be a time of joy, excitement and fear. Few women had not known of the death of women and babies in childbirth. Experienced family members and neighbours assisted births, and while they had no formal training, they often had significant practical experience.

It was safer to give birth at home. Across the world in Britain, there was a growing discovery that the fatal puerperal infection affecting so many mothers was being passed from mother to mother by the doctors themselves[12]. Now we can look back and see the devastation caused during this time before antibiotics, before infection control was understood, before safer interventions to assist prolonged labour were available. Between 1870 and 1890 in Britain the maternal mortality rate ranged from 40 to 80 per 1,000 births. By 1970 this had dropped to around 1 death per 1,000 births.[13] Unfortunately, the fear of birthing mothers and the women around them was founded on sound experience. It seems likely that Julia’s mother and the women of the town supported her during childbirth;

In the quiet moments of the early December morning, as she began her chores, Julia contemplated how she felt. Her back was aching more than usual. The sleepless nights were draining the small amount of energy she had with no less work to be done. Today, the dripping humidity was holding the smoke from the fire close, overpowering the scent of the bush she so loved, and drawing breath seemed impossible. It was then Julia became aware that the pains rolling across her stomach were not the infrequent practice pains she had been having. These pains were becoming stronger, gripping her attention and settling into regular increasing waves. She had to stop what she was doing to concentrate until the pain passed. Julia felt both fear as the contractions built in intensity and a wish to run away from it all, but also kinship with all those women who had given birth before her. Looking up, Julia felt relief and a flutter of excitement as she saw her mother and sister coming towards her.

Despite the known risks and her deteriorating health and heart, this birth would be the first of six babies born to Julia, all to survive. There may have been other pregnancies, unrecorded, but the six babies are closely spaced at 17, 19, 12, 23 and 33 months apart.

Based on my own experience of giving birth to three children in the late 20th century, it is difficult to comprehend how Julia coped through multiple close pregnancies, childbirth and child-rearing. In contrast to my experience where skilled midwives and doctors were available whenever needed, a hospital was nearby for an emergency Caesarean section, treatment to stop bleeding, antibiotics for infection and specialised support when a baby was distressed. I also had the benefit of good nutrition and health monitoring. I took most of this for granted until imagining the situation Julia found herself in.

As the strength and length of contractions increased, Julia looked to her mother for reassurance. Her mother, Alice, had helped many women give birth both on the Goldfields of Australia and more recently in the neighbouring town of Brunnerton. A strong, resilient woman who had survived the death of two husbands and several of her babies. A woman who had given birth to her children in various testing circumstances from the slums of London’s East End to the pioneering goldfields of Australia. Today she would assist her daughter in safely birthing her first child.

Personally, I had choices about whether I would have children or not, whether I would continue with my work, and whether my husband or I would be the primary caregiver. For Julia, being a good wife and mother would be considered her key role. It was a time when “the carrying, birthing and rearing of so many children to maturity created much anxiety and took a heavy toll on the energy and health of the mother”.[4] Energy and health, Julia did not have.

Phthisis (now known as Tuberculosis) was romantically described as the “white death” owing to the anaemia and weight loss that occurred. Commonly there would be increasing difficulty breathing, night sweats, a persistent cough and haemoptysis (coughing blood). Over time the lungs and heart struggle to work efficiently causing increasing fatigue.[15] Each pregnancy would likely increase Julia’s symptoms and deterioration.

Now, with a range of contraception available, it is difficult to imagine why, given her ill-health, Julia and Edward had children so frequently. In the 1880s, the only contraception available was abstinence or withdrawal[16].

On the 4th of December, 1881, her firstborn was a daughter with tight dark curls, huge dark eyes and olive skin. This was my great grandmother, Lydia Ann Woodford, who showed resilience and tenacity like her mother and grandmother. She lived a long life, surviving her mother’s death at age ten and later giving birth to eight children of her own, including twins.

Lydia Ann was Julia and Edward’s first child, their last child, a son, William Albert, was only six months old when his mother died. William Albert also lived a long life, married and had five children, all of whom lived until adulthood. Edward too, lived well into his 90th decade, remarrying several years after Julia’s death.

The 1890s were significant for the women of New Zealand, change was coming. Unfortunately with Julia’s failing health and death in 1892, she did not live to enjoy what women achieved nor benefit from the improvements in health services. In 1893, one year after Julia died, the women of Aotearoa New Zealand became the first in the world to be able to participate in the political process.

In 2021, I visited the He Tohu exhibition in Wellington. Walking through, I entered a darkened room containing three dimly lit cases, each holding the remnants of documents that had shaped Aotearoa New Zealand. A moving collection including He Whakaputanga (Declaration of Independence [17] signed in 1835, Te Tiriti o Waitangi (The Treaty of Waitangi) [18]signed in 1840 between Maori tribal leaders and representatives of the English government and the Womens’ Suffrage Petition. [19]I stood in the centre, overwhelmed at the importance of these documents, the changes they brought, and the history they contained.

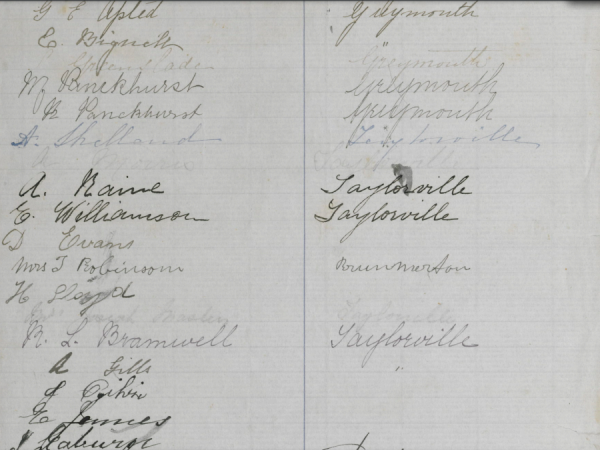

I moved between each document feeling awe and wonder, seeing and sensing the human effort that had created each one. Finally, as I stood before the Women’s Suffrage Petition I felt my breath catch as I thought of those many courageous women embodied in the document. The honour felt to see that vast scroll of paper and imagine those committed women glueing each piece together. They could only have been proud and strengthened in their resolve by seeing the inked signatures of the 25,000 women who signed the petition as the women travelled the country gathering signatures. This petition presented to parliament was the final driver for change, critical in obtaining the vote for women in 1893. Julia did not live to see this day nor sign the Suffrage petition but I was excited and proud to find the faded signature of her sister, Mrs Alice Elizabeth Morris.[19] Alice and several other local women had signed the petition as it circulated every part of the country including their small remote town of Taylorville.

Outlived by her husband, leaving six small children, one a baby of just six months old, Julia died in 1892 and was buried in the nearby Stillwater cemetery. Here, her story also remains silent. Julia’s burial and that of her mother, stepfather and sister are recorded on their official death certificates, yet no trace remains in the Stillwater cemetery or records.

Julia’s voice lives on through many descendants. As a proud and loving descendant making my journey to the West Coast, I could not help thinking that those women of early generations had lead extraordinarily tough and unforgiving lives.

Could it have been the breath of my ancestors whispering as my 2021 train journey travelled through Stillwater, or was it just wild imagination as we passed the place of their unmarked graves? With the cold biting into every piece of exposed flesh, I was encouraged to move back into the warmed carriage and comfortable seat to contemplate earlier times.

Melanie Atkins 2021

CITATIONS AND BIBIOGRAPHY

[1] Registrar of Marriages Greymouth NZ, ‘Woodford Appoo Julia Euphemia 1880 Marriage certificate’.

[2] ‘Lenny Broken Wrist GREY RIVER ARGUS, VOLUME XXIII, ISSUE 3664, 24 MAY 1880, PAGE 2’, Grey River Argus, vol. XXIII, no. 3664, p. 2, May 24, 1880.

[3] ‘Cost Birth Death Marriage Notice’, West Coast Times, no. 836, p. 2, May 28, 1868.

[4] ‘Wallsend Taylorville The Grey River Argus. Published Daily. Saturday, May 26, Iss3. , the Grey River Argus. Published Daily. Saturday, May 26, Iss3.’, Grey River Argus, vol. XXX, no. 4603, p. 2, May 26, 1883.

[5] Williams, Lyn, ‘George Fraser The builder of bridges – Wallsend Taylor Bridge’, Waikato Times, Feb. 08, 2019. https://www.pressreader.com/new-zealand/waikato-times/20190208/282415580534447 (accessed Dec. 06, 2021).

[6] Oakley, Peter Harold, ‘Taylorville School centennial celebra… | Items | National Library of New Zealand | National Library of New Zealand’. https://natlib.govt.nz/records/21087201?search%5Bi%5D%5Bcategory%5D=Books&search%5Bi%5D%5Bsubject%5D=Grey+District+%28N.Z.%29+–+History&search%5Bpath%5D=items (accessed Dec. 12, 2021).

[7] Stackhouse John, ‘Down the Pit West Coast Mining’, Mem. Mag., no. 147, pp. 38–46, Jan. 2021.

[8] ‘Brunner Mine Accidents’, Colonist, vol. XII, no. 1265, p. 2, Nov. 09, 1869.

[9] ‘Papers Past | Newspapers | New Zealand Herald | 2 December 1872 | Page 1’. https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/new-zealand-herald/1872/12/02/1 (accessed Sep. 21, 2021).

[10] J. Ring and N. Z. M. for C. and H. T. M. Taonga, ‘Grey Hospital, 1890s’. https://teara.govt.nz/en/photograph/27542/grey-hospital-1890s (accessed Dec. 28, 2021).

[11] E. Hawker, V. Corbett, National Council of Women of New Zealand, and Greymouth Branch, Women of Westland, 1860-1960. Greymouth, N.Z.: Greymouth Evening Star, 1959.

[12] ‘Postpartum infections’, Wikipedia. Jul. 07, 2021. Accessed: Dec. 10, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Postpartum_infections&oldid=1032438678

[13] G. Chamberlain, ‘British maternal mortality in the 19th and early 20th centuries’, J. R. Soc. Med., vol. 99, no. 11, pp. 559–563, Nov. 2006.

[14] D. Beechey, ‘Eureka! Women and birthing on the Ballarat goldfields in the 1850s’, Thesis, ACU Research Bank, 2003. doi: 10.26199/5d7afd641b752.

[15] J. Frith, ‘History of Tuberculosis. Part 1 – Phthisis, consumption and the White Plague’, JMVH, vol. 22, no. 2, [Online]. Available: https://jmvh.org/article/history-of-tuberculosis-part-1-phthisis-consumption-and-the-white-plague/

[16] M. Editor, ‘Contraception and reproduction in Australia’s past (or: please don’t try these methods at home)’, Australian Women’s History Network, Feb. 19, 2018. http://www.auswhn.org.au/blog/contraception-dont-try/ (accessed Jan. 10, 2022).

[17] Ministry for Culture and Heritage, ‘Declaration of Independence’, New Zealand History, Nov. 02, 2020. https://nzhistory.govt.nz/culture/declaration-of-independence-taming-the-frontier (accessed Dec. 08, 2021).

[18] ‘Treaty Of Waitangi | NZHistory, New Zealand history online’. https://nzhistory.govt.nz/politics/treaty-of-waitangi (accessed Oct. 27, 2021).

[19] ‘Women’s suffrage petitions presented to Parliament’, New Zealand History. https://nzhistory.govt.nz/petitions-with-9000-signatures-demanding-the-vote-for-women-presented-to-parliament (accessed Nov. 26, 2021).

ADDITIONAL REFERENCES

[20] S. Battye and T. Eakin, ‘The mine’s afire!’: the journal of Tommy Carter, Brunnerton, 1896. Auckland [N.Z.: Scholasitc New Zealand, 2009.

[21] ‘RESULTS OF A CENSUS OF THE COLONY OF NEW ZEALAND taken for the night of the 28th March 1886’. https://www3.stats.govt.nz/Historic_Publications/1886-census/Results-of-Census-1886/1886-results-census.html#d50e4136 (accessed Nov. 27, 2021).

[22] L. Radford, ‘The Reality of Childbirth in the 1800s’, Curious Historian. https://curioushistorian.com/the-reality-of-childbirth-in-the-1800s (accessed Dec. 05, 2021).

[23] ‘The Wild West’, Courageous Colonials. https://courageouscolonials.com/brunnerton-wallsend-dobson-taylorville/ (accessed Dec. 06, 2021).

[24] McCaskill, M, ‘Historical geography of Westland before 1914 – Volume 2’. Accessed: Dec. 12, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://ir.canterbury.ac.nz/bitstream/handle/10092/4762/mccaskill_thesis_vol2.pdf?sequence=2

[25] R. Jones, National Council of Women of New Zealand, and Westland Branch, Women of Westland and their families. a sesquincentennial project of the National Council of Women, Westland Branch Volume III Volume III. Greymouth, N.Z.: The Branch, 1990.

Just showing my sister Jo your fabulous site Mel. I hope some of your expertise rubs off on me. Chris X

I have you to thank for getting me started. Such strength and resilience in the women inspires stories.