Pearl and Ruby

Two lines in my mother’s family history record drew me in: ‘Ruby Horn was born and died in 1899. Pearl Horn was born and died in 1899’. These brief facts were all it took to set me on a path of wondering and learning.

“I wonder where this family lived when this happened?”

A quick search showed the family lived in Wellington, Aotearoa New Zealand. A country described by an early settler as “Britain by the Sea”[1] in a city where the wealthier inhabitants modelled their homes, interiors, clothing, and social entertainment on what was learned from British Newspapers, then ensured this mimicry was described in detail in local papers[2]. In 1899 Wellington was still a relatively new city. Only 34 years earlier it had snatched the title of capital of Aotearoa New Zealand from Auckland.[3]

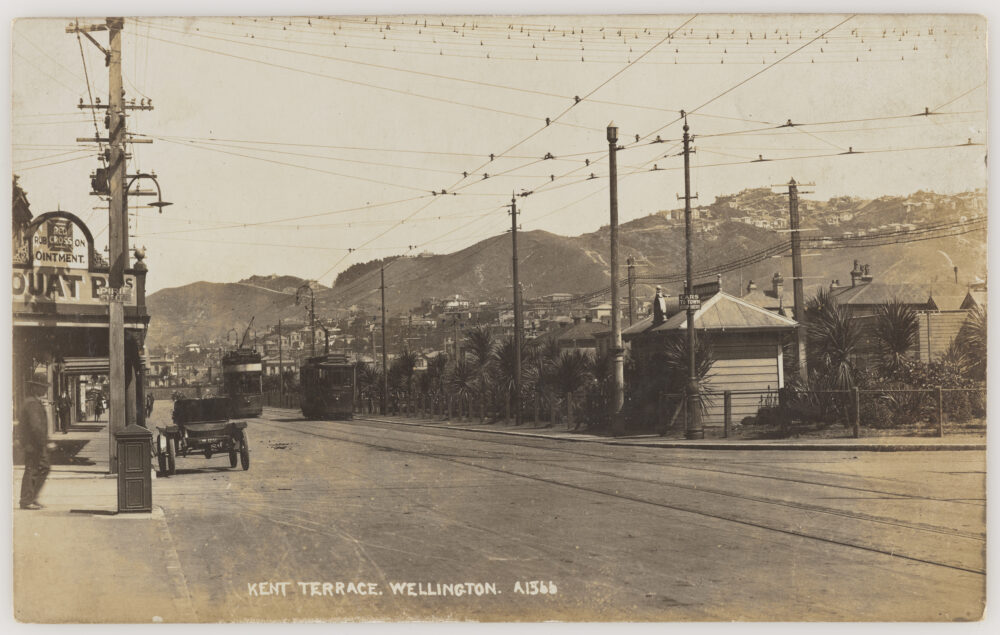

Māori Iwi (tribes) had lived across the area since at least the 13th century; more recently, around 1839, settlers from across the world had begun to arrive.[3] Wellington was a growing city and Kent Terrace where the Horn family lived already had a row of buildings lining the street and tram rails through the centre.

William Hutcheson Horn and Alice Annie Maud Rudman Horn do not appear to have been presented on the social pages of the newspaper. Alice had lived all her life in Wellington.

“I wonder what happened to Ruby and Pearl?”

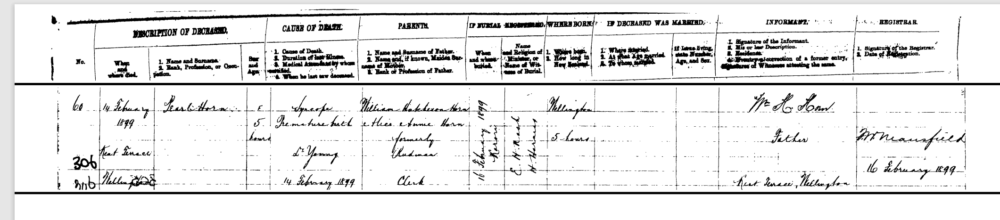

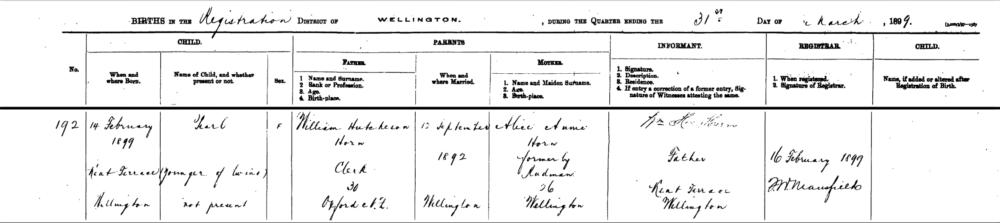

Research quickly revealed Ruby and Pearl were twins, both of whom died soon after birth. [4] [5] Dr Young, a well-known local Doctor in Wellington signed their death certificates.[6] Dr Young recorded that Ruby and Pearl’s deaths [7] [8] were caused by premature birth and Syncope. Oddly this term is more commonly used during the Victorian era to describe women “swooning” or fainting.[9] A lack of blood supply to the brain is the likely meaning here.

In 1899 influenza was spreading rapidly through Aotearoa New Zealand along with a rubella epidemic.[10] Whether either epidemic impacted Ruby and Pearl’s premature births is unknown but possible.

Dr Young recorded that wee Ruby (the older twin), died half an hour after birth[5] [8] and little Pearl [4] [7] five hours later on 14th February 1899.

“But that is Valentine’s Day. Wait – did they have Valentine’s day in 1899?

Browsing newspapers confirmed Valentine’s Day did exist in 1899, arriving in New Zealand around 1876. Each year newspaper articles detail the history of St Valentine’s Day brought to Aotearoa New Zealand, as it developed into a day for the celebration of romantic love.[11]

So popular was Valentine’s Day that soldiers keen to remember their Valentine during the Boer War worked to find a way to celebrate their love, even in the theatre of war. From 1899 onwards, New Zealand soldiers fighting in the Boer War in South Africa made little hearts on the only medium available – their Khaki uniform cloth.[12]

“Valentine’s day is probably irrelevant to a mother who has lost both her babies. The sense of grief and loss is unimaginable.”

Valentine’s Day 1899 likely meant little to Ruby and Pearl’s mother Alice. Imagine those feelings: That whisper in your head –“It is too soon, don’t come now little ones”. The searing pain that seems to ooze out from your heart, the lifeless exhaustion in your limbs, your body empty yet unfulfilled, your mind leaping from life to death and back again. The strong desire to cry out, to wail, pitting itself against the desire to nurture and protect.

It would seem there have been many changes over past centuries in the way we think, speak, interact, love, yet surely some human responses remain unchanged, surely the loss of your child remains as grief-filled then as it is now.

“Where were the twins born?”

Pearl and Ruby’s birth and death certificates state they were born and died at Kent Terrace Wellington.[5] There is no record of the exact address- likely, this was home. Birth at home was still the most common, with the alternative of hospital births beginning to be recognised.

While Alice probably noticed little of the day outside, the weather as always in the windiest city in the world – was windy. The temperature peaked at a mild 20c. There were blue skies, over which floated the ever-present white cloud[13] that had prompted the Māori name for the land – Aotearoa.

“What about Ruby and Pearl’s father William?”

Depending on the time of the girls’ births, William may have been at his work as a Clerk. It was uncommon for a husband to be with his wife during childbirth. It is my hope he was there to share grief and comfort afterwards.

My grandfather remembers that his Uncle William was a member of the Salvation Army. Annie Rudman, Alice’s mother, was reported as one of the first to join the Salvation Army when it began in New Zealand.[14] A photograph taken during the 1890s shows Alice and her sister Eva sitting on either side of their mother, Annie Rudman. The three women are sitting stiffly, without a smile, all wearing Salvation Army uniforms.[15] Maybe Alice and William gained solace from others in the Salvation Army congregation.

In the days and weeks after the births, distraction and some comfort may have come from the preparations underway for a visit by William Booth the following month. William Booth, the founder of the Salvation Army in Britain, was arriving on his first of what was to be four visits to Aotearoa New Zealand.[16]This visit and the focus of his wife Catherine on equality and inclusion of women within the Army may have given Alice strength.

“I wonder if there were other children?”

Family history records showed that at the time the twins were born Alice and William had two children – the oldest was a girl Ivy Lillian 6 years old, and a son Horace Victor Clarence 3 years old. Alice would also outlive both these children, Ivy died in 1922 from Influenza, and their only son Horace died at 24years of age, post World War 1.

It was five years after Pearl and Ruby’s deaths before another birth is recorded. Alcia Hazel Evelyn Annie was born in 1904, and three years following that, Olive Marjorie Selwyn was born. Olive was not shown in family records, yet descendants carry her name. Both women lived into their old age.

“What happened after the twin’s death?”

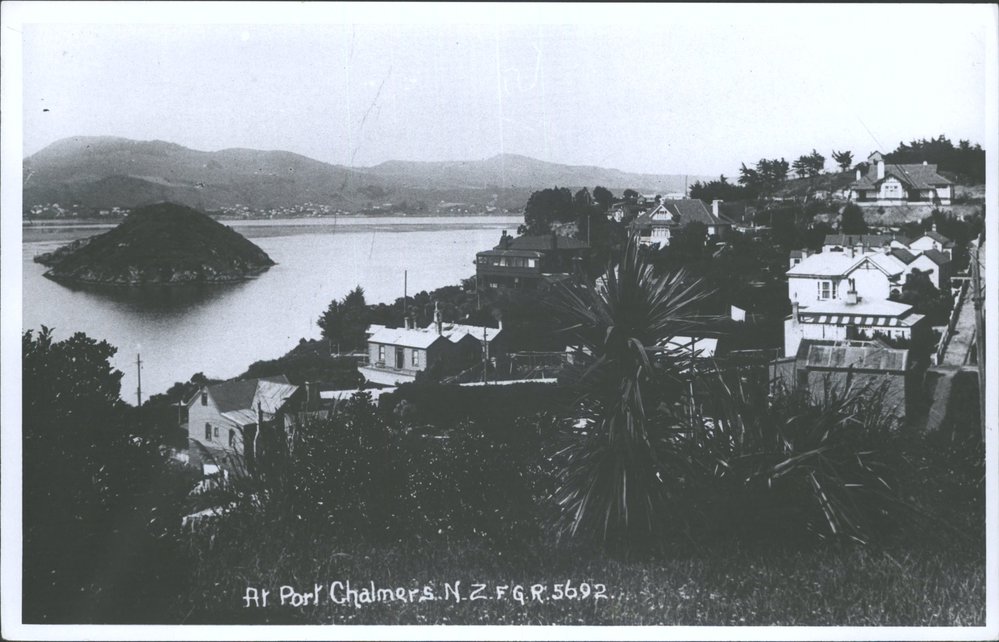

Alice had lived her life in Wellington, yet within two years of the twin’s deaths, Alice and William had moved to the colder southern part of the South Island, settling in Port Chalmers. Was it because of the deaths of their wee daughters?

Port Chalmers was the port serving the southern city of Dunedin. The small population of approximately 2,000 is spread over a hilly peninsula. Early expeditions called in here on their way to Antarctica for last stop repairs and provisions. The port was also well known for shipbuilding, particularly early steamships.[17] Here the Salvation Army had begun in New Zealand years earlier.

William and Alice remained in Port Chalmers until after William’s death. Some time after this Alice returned to Wellington; records show her death and burial in Wellington in 1940.

My discovery of Ruby Horn had been accidental, a random selection of who in my ancestral family to think about next. The discovery led me to research a tale of two forgotten girls. Ruby and Pearl are easily overlooked as we seek living connections. Yet their brief story revealed strands of social and family history that I may not have considered without seeking their story.

Pearl and Ruby, you are remembered,

Melanie Atkins 2022

Writing about my great great Uncle William Hutcheson Horn, his wife Alice Annie Rudman Horn and their daughters Pearl and Ruby Horn.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

[1] Barker Mary Anne, ‘ENZB – 1904 – Barker, Mary Anne. Colonial Memories [New Zealand chapters] – I. OLD NEW ZEALAND, p 1-20’. http://www.enzb.auckland.ac.nz/document/?wid=5487&page=0&action=null (accessed Feb. 07, 2022).

[2] D. A. Hamer, The Making of Wellington, 1800-1914. Victoria University Press, 1990.

[3] ‘Wellington’, Wikipedia. Feb. 16, 2022. Accessed: Feb. 16, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Wellington&oldid=1072134257

[4] ‘Horn Pearl New Zealand, Birth Index, 1840-1950 – Ancestry.com.au’. https://search.ancestry.com.au/cgi-bin/sse.dll?indiv=1&dbid=8949&h=406978&tid=&pid=&queryId=773d0c6d21c82a2ab7a9d2b8cd64efc3&usePUB=true&_phsrc=662-134824&_phstart=successSource (accessed Feb. 14, 2022).

[5] ‘Horn Ruby New Zealand, Birth Index, 1840-1950’. https://search.ancestry.com.au/cgi-bin/sse.dll?indiv=1&dbid=8949&h=406979&tid=&pid=&queryId=8040d7329447a2dfebbc32d610378220&usePUB=true&_phsrc=662-1905684&_phstart=successSource (accessed Feb. 13, 2022).

[6] ‘Dr Young in Doctors in Conference , Doctors in Conference’, New Zealand Mail, no. 1514, p. 33, Mar. 07, 1901.

[7] ‘Horn, Pearl. 1899 Death “New Zealand, Civil Records Indexes, 1800-1966” • FamilySearch’. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QG6K-HDJC (accessed Feb. 13, 2022).

[8] ‘Horn Ruby 1899 Death “New Zealand, Civil Records Indexes, 1800-1966” • FamilySearch’. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QG6V-BHY9 (accessed Feb. 13, 2022).

[9] N. van Dijk and W. Wieling, ‘Fainting, emancipation and the “weak and sensitive” sex’, J. Physiol., vol. 587, no. Pt 13, pp. 3063–3064, Jul. 2009, doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.174672.

[10] B. Huf and H. Mclean, ‘Epidemics and pandemics in Victoria: Historical perspectives’, p. 40.

[11] N. Z. M. for C. and H. T. M. Taonga, ‘Valentine’s Day, 1876’. https://teara.govt.nz/en/document/31202/valentines-day-1876 (accessed Feb. 13, 2022).

[12] ‘A Khaki Valentine’, Auckland War Memorial Museum. https://www.aucklandmuseum.com/discover/stories/blog/2021/A-Khaki-Valentine (accessed Feb. 11, 2022).

[13] ‘Meteorological. to-Day’s Weather , Meteorological. to-Day’s Weather’, Evening Post, vol. LVII, no. 37, p. 4, Feb. 14, 1899.

[14] N. Z. M. for C. and H. T. M. Taonga, ‘Rudman, Annie’. https://teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/2r29/rudman-annie (accessed Feb. 14, 2022).

[15] N. Z. M. for C. and H. T. M. Taonga, ‘The Salvation Army’s early days’. https://teara.govt.nz/en/salvation-army/page-1 (accessed Feb. 09, 2022).

[16] ‘Salvation Army Our History’, Jun. 16, 2008. https://archives.salvationarmy.org.nz/our-history (accessed Feb. 09, 2022).

[17] ‘Port Chalmers’, Wikipedia. Jan. 07, 2022. Accessed: Feb. 17, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Port_Chalmers&oldid=1064193571