Ruth and Adeline

This story is based on facts discovered about the lives of my ancestors. Unless referenced the feelings and interpretation of events are imagined. I am indebted to the first-hand information provided in the memoirs of Eva Florence Robinson[1] and Edna Robinson [2] for details of life in Nuggety Creek.

Content Advisory This story includes death and accidental injury.

As a woman who paid attention to portents, Ruth Woodford may have predicted a difficult year in 1929. Ruth and her older sister Lydia Ann (my great-grandmother) held a close bond and a keen sense of omens; a picture falling from the wall signified bad news coming.[3] We cannot know if the heavy thud of a picture falling to the floor foretold what 1929 held for Ruth. Could she have imagined that in one year a national disaster, an international crisis and a family death would impact her life and family?

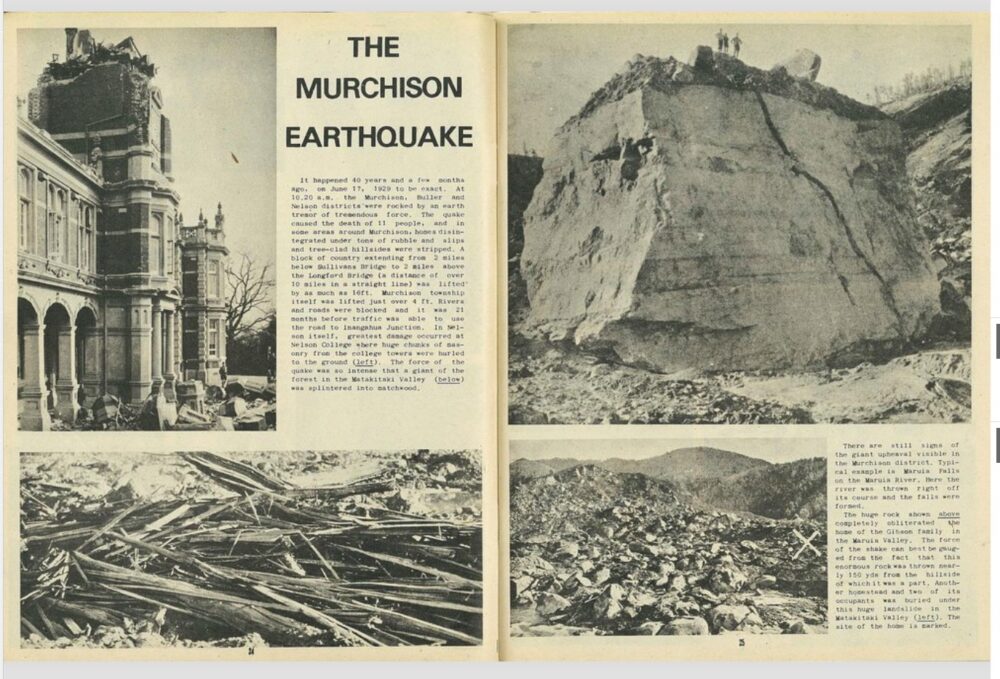

The Murchison earthquake, a major national disaster, struck on June 17, 1929, at 10:17 am.[4] Its epicentre was close to Nuggety Creek, a far-flung settlement where Ruth Woodford, her husband Robert Pace Robinson, and their extended family lived. Close by was the small town of Murchison in southern Aotearoa New Zealand (NZ).

For the Robinson and Woodford families, this story had begun seventeen years earlier. In 1912 four families had packed their few belongings, and carrying the necessary tools and equipment set off to establish a new life. Leaving behind the rugged, wild, West Coast and the bleak coal-mining region that had been home, the families travelled further south to their newly purchased remote piece of land at Nuggety Creek.

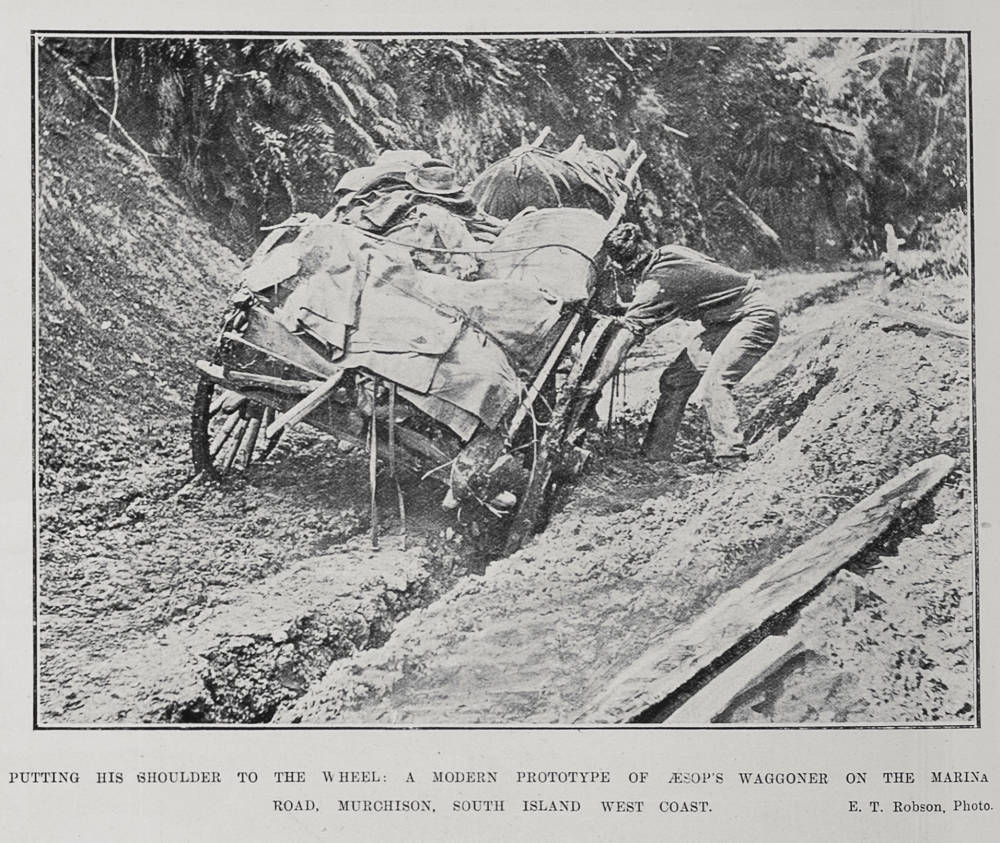

One imagines travelling on an overly warm day in the summer of 1912, those humid days when sweat drips and clothes stick to the skin. Young girls grip the side of the horse cart squealing and giggling with each bump as it jolts along the poorly made and overgrown track. While the boys, barely sitting still with excitement, are shouting over each other “When we get there, I’m gunna …”. The explanation that the track they are travelling along was built for the early gold prospectors [5] only escalates their imaginings. The parents walk alongside or drive the horse and carts slowly down the rutted track. Unseen by the children are the dogged stares of the men and the creased frowns of the women as the city of Nelson fades behind them. Travelling towards an unknown future as the mountainous landscape and impenetrable bush stretches out before them.

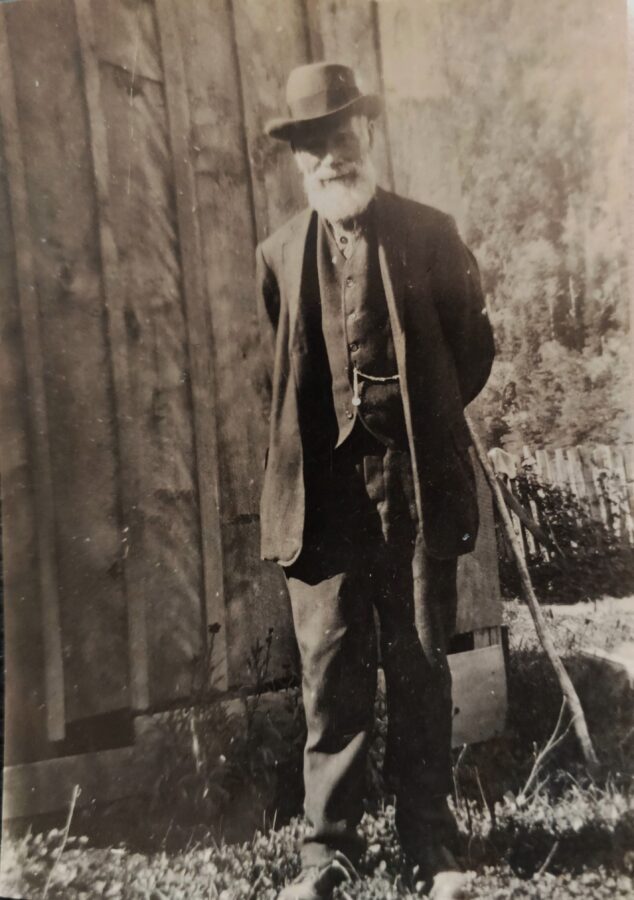

It would likely have been comforting to see their Grandfather Woodford striding without pause alongside his stocky, slow, but reliable horse. Reassuring to see his lined face without worry, framed by hair streaked white, and his familiar long greying beard, neither completely masking the handsome features of his youth. Close by jolting along on a wagon the equally comforting presence of Grandmother Eva sitting straight-backed, her face reflecting a no-nonsense look as she sternly reprimanded any child whom she felt was ill-behaved.

Perhaps Grandmother was travelling in the cart of her son Joseph Pace Robinson, who had sustained a serious head injury in an accident down the mine. It was a compensation payment from this accident that enabled the purchase of the piece of land they now travelled towards. [1] It held the promise of a farming life and an escape from the dirt and danger of coal mining. Joseph now led the family along the difficult track keeping a lookout for falling rocks and slips common along their route. A route that traversed rivers, wound along narrow tracks and passed through steep gorges overwhelmed by the ominous, dark, fern-lined bush filled with a myriad of bird song deafening in the dawn and dusk.

The children likely shared their delight in the storybook name of their new home – Nuggety Creek. Not yet understanding the isolation, hard work, and challenges ahead. The adults were acutely aware of the tasks that would be needed to establish homes and livelihoods for their four families. The land to be cleared and burned, a sawmill built, wood milled to build houses, grass and crops sown on the cleared flat land, a house built for each family and finally the homemaking. The latter being the purview of the women. Interior painting and decorating including making drapes, furnishings and simple furniture. All would be constructed from materials at hand; sacking, flour bags, and worn clothing [1], [2] reimagined and repurposed.

Eventually, once the land was cleared, grass established, homes built and officially surveyed, the houses would be moved a distance apart. Possibly the beginnings of a NZ habit that continues to the current day. Known as a “shifty” – an entire house is lifted and moved by truck from one location to another. Nowadays often many kilometres.

The children would soon discover the new freedoms and the hardships of living at Nuggety Creek. The unfettered freedom to roam the lush, dense bush and rocky riversides. Games once played indoors such as ‘Hide and Seek’ could now be outdoors without boundaries. Whether for work or play there was the thrill of riding bareback – gripping the warm flanks of the horse, with hands entwined in the wiry mane as the horse sped across the land. Taught early to use rifles, the boys were exhilarated by the real-life hunt for large red deer through the dark pathless bush. They displayed a steely bravado as the sound of the rifle ricocheted around the mountains and vibrated through their small wiry bodies. The young girls were tasked with following along to help carry the heavy and often bloodied deer carcass back home.

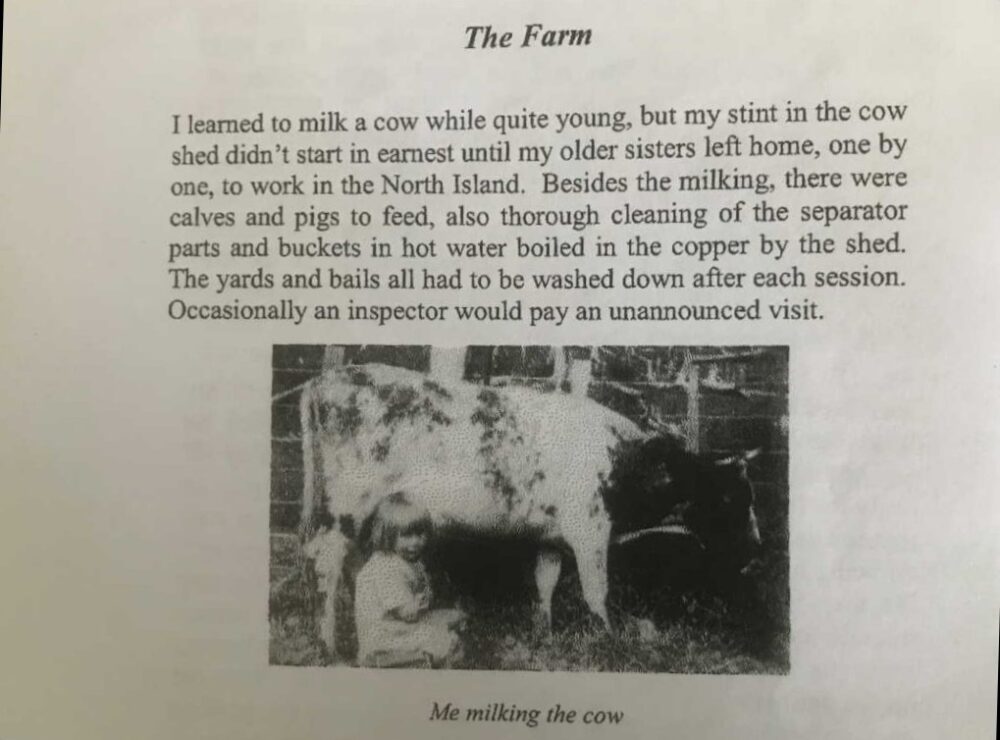

Along with new freedoms, chores were allocated to each child according to age. New and more responsible chores were added as they grew. The children often rose long before fingers of sunlight crept over the mountains. Fading night sounds of “More-Pork. More-Pork” the soulful call of the Ruru owl echoing across the valley. Chores had to be done, whether in the deepest chill of a snow-laden winter, the blinding rainstorms that penetrated their carefully handstitched clothing, or the sticky heat of midsummer. Reluctantly mucking out animal pens as the stench of manure engulfed them. Bringing in and milking the cows, feeding the snuffling, snorting pigs, scattering scraps for the chooks, and collecting the fresh hens’ eggs. All animals had to be cared for. The boys were tasked with gathering firewood, then chopped, and stacked. Working alongside their fathers, they would remove trees, bushes, and rocks from the land. Help to build farming structures and prepare the unforgiving ground for planting. The girls would help with harvesting the seasonal foods and working alongside the women to prepare meals, take care of the home, and the men. [2]

It was into this family community that Ruth, Robert, and their six children moved in 1917. Five years after their families had settled there, and seventeen years after their marriage.[9] At the head of this community were Ruth’s father, Edward Spencer Woodford, and Robert’s mother, Eva Pace Robinson, who had married in 1901[10], four years after the death of Ruth’s mother Euphemia Julia Woodford – Edward Spencer’s first wife. Their marriage had taken place a year after Ruth, (then a 17-year-old) and 25-year-old Robert had married [9].

An itinerant worker, Robert had always moved to wherever he could find work whether as a sawmill hand, farm labourer, bricklayer, roadman, or coal miner.[11] After marriage, this also became the way of life for Ruth and their growing family. The support of extended family and a home at Nuggety Creek enabled Ruth and the children to put down roots while Robert continued to work wherever work was available, often away. The move to Nuggety Creek had come after spending most of their early married life in West Coast coal-mining towns where life was rugged and community spirit was strong.

West Coast Coal mining began commercially in the mid-19th century following the discovery of high-quality coal in the region.[12] In those early years of mining, it was mostly done with the labour of the local Māori people. Before long special immigration status was given to miners from the United Kingdom at the request of the coal mining company struggling to keep up with the worldwide demand for the jet-black coal that proved ideal for fuelling heavy industry. The need for miners rapidly increased, leading to the employment of immigrants keen for work but often without experience.[13] Robert’s father Matthew was one of these workers working as a shipbuilder in Durham England [14]. On emigrating Matthew described himself as an ‘Engine-man’- likely working above ground in a colliery in Northern England. West Coast mining work was in dark damp underground tunnels, lit only by the headlamps of the miners and surrounded by stale air and risk. Risk was constant: explosions, rock falls, tunnel collapse, accidents with coal wagons, and escaping poisonous gases.[15] A catastrophic injury in the mine led to Matthew’s confinement at home where he was nursed by his wife Eva until his early death.

Robert’s brothers and stepfather, Edward Spencer Woodford, also worked in the mines. His brother Joseph was also seriously injured in a rock fall while down the mine. Again the nursing skills of Eva his mother were much needed after Doctors ceased to treat him. [1]

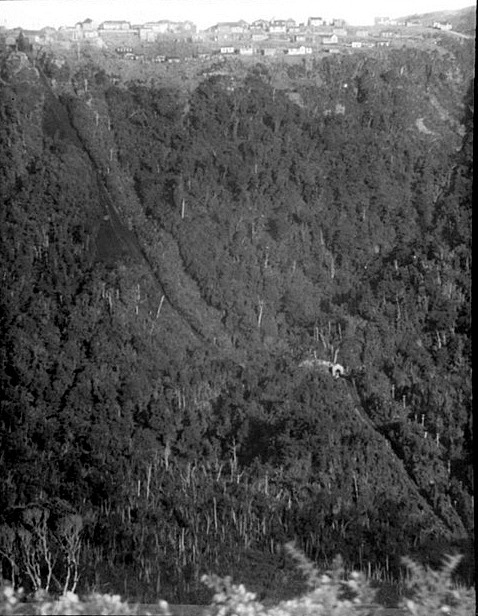

During their early years of marriage, work in the coal mines took Ruth and Robert to Denniston, described as ‘one of the most remote and difficult mining towns to live in”. A coal mining town atop an almost perpendicular hill. The only access was via a steep, often slippery, log-lined bridle path. For the desperate, or foolhardy, there were the coal carts that rumbled up and down the Denniston Incline. As a feat of engineering locals dubbed it the “eighth wonder of the world”. [17] Yet the almost vertical incline with its potential for runaway carts and collisions meant a perilous (and forbidden) ride in the high-speed coal carts. After their first heart-thumping journey to Denniston, some women refused to make the journey again, choosing to remain isolated in the hilltop mining town for life.

Ruth, Robert, and the children would have lived with other families clustered near the mines in draughty huts and houses perched on a rocky exposed plateau, high above the sea. A treeless habitat, with minimal vegetation. Mud and rain were plentiful, and the birdseye view to the Tasman Sea was often obscured by fog and mist. A bleak landscape where even the strong arms of mine workers could not dig graves in the hard rock. The dead would be taken in the coal carts down to the towns below for burial.

It was here, in this unforgiving landscape that Ruth gave birth to their first child, a son Matthew, in 1901. Women in the grip of labour pains would at times choose to walk down the vertiginous and uneven path to be able to give birth in the town below. Though it is not known how her choice was made, it would seem Ruth remained in Denniston for the birth of her first child.

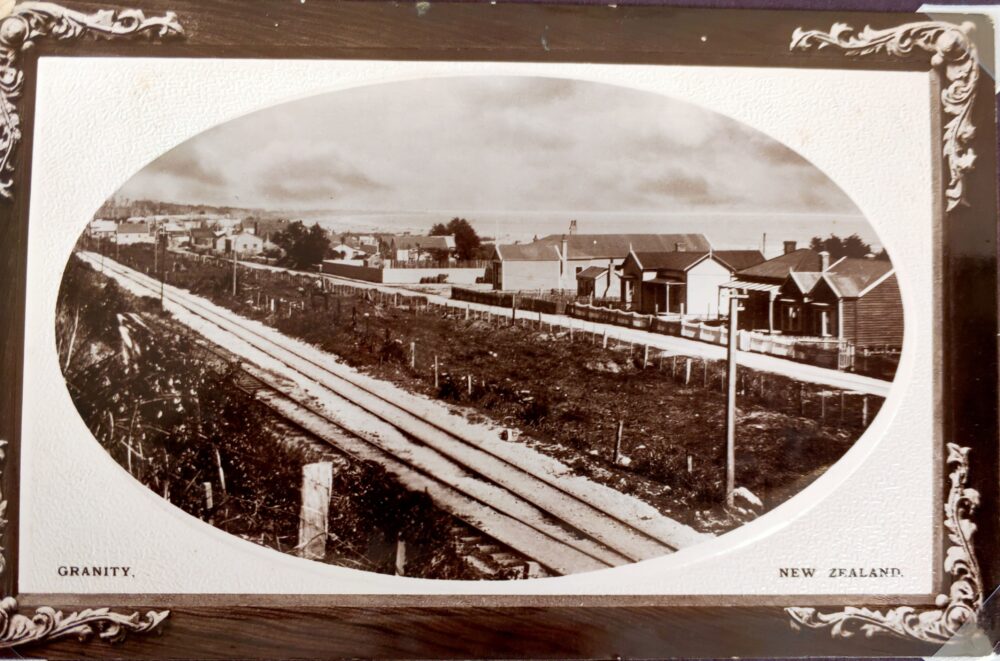

Seeking work, the growing Robinson family moved frequently before settling at Nuggety Creek, often returning to the coal mining towns of Denniston and Granity. While the idea of a small seaside town on the coast might have seemed an improvement on their life in Denniston, Granity was no less challenging for a mother with small children. The coal-mining town was wedged between the Tasman Sea bringing icy blustery weather from Antarctica, and the impenetrable native forest cascading down mountainsides into the dark, dusty coal miners’ landscape below.

Granity entered the 20th century with a population of just 366. Here it was coal mining and sawmilling rather than people who were the priority. Trains frequently rumbled through the centre of town spewing dust and fumes as they transported the sought-after coal to the harbour for shipping to the industries of England. The coal-mining company supplied free electricity to public buildings, such as the Library and Masonic Hall, but not to the coal-miner’s families.[19] Local families including the Robinsons would have to purchase the coal for their household. Despite her small, slight appearance, Ruth would have needed strength to cart the heavy buckets of black coal for daily chores and heating: stoking the fire under the copper for the family wash, keeping the oven alight for cooking summer and winter, boiling water for bathing the coal dust and sweat off bodies. Stamina was needed to stir and pound the family wash clean in the copper, to wind the hand-turned wringer, and to heat the heavy flat iron on the stove to press all garments and household linen. The coal-fired stove would need attention year-round to prepare meals, bake bread, ferment yeast, and boil water for household use.

Ruth must have been delighted when in 1902 her dear sister Lydia chose to make the rough sea journey from her North Island home in Whanganui to Granity to give birth to her first child – Eva Naomi Wilson (my grandmother). Family recollection is that Lydia wanted the support of her midwife stepmother, Eva Woodford,[20] and her sister Ruth. Commonly women gave birth at home with support from neighbourhood women and midwives. [21]

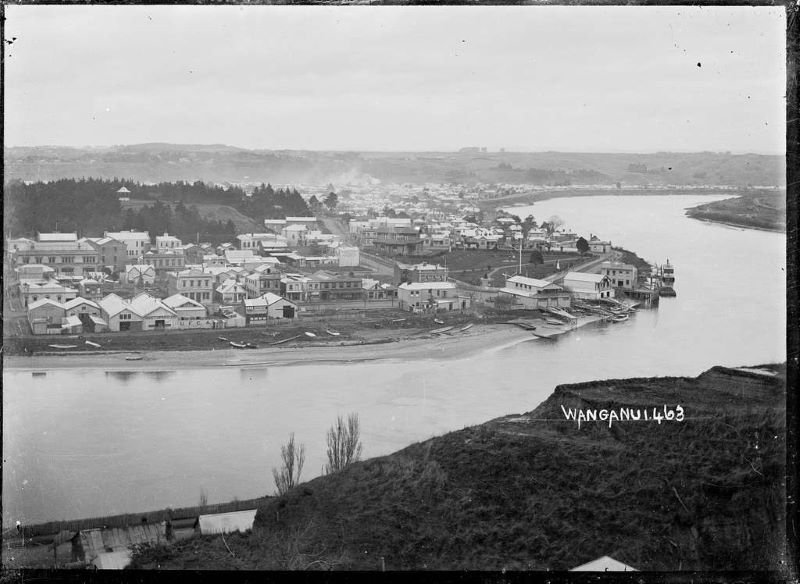

Lydia, along with Alice Edna, (their younger sister) lived in Whanganui, a picture-perfect town straddling the wide Whanganui River mouth. Life here would have seemed idyllic away from the soot and black of coal mining. For a short time, Ruth and Robert moved to Whanganui where their fourth and fifth children were born; Thomas Edward who died soon after birth, closely followed by the birth of Adeline Ruth Robinson in 1908. Two years later the family left Lydia and Alice to move back to the West Coast, likely seeking work for Robert.

Finally, in 1917 Robert, Ruth and their (now eight) children moved south to join their extended family at Nuggety Creek. Here two more children were born. While her sister Lydia remained in Whanganui, Ruth would have had the assistance of Grandmother Eva Woodford, registered as a trained Nurse and Midwife.

In June 1929 after years of hard work establishing their family settlement, unfamiliar booming sounds reverberated through the mountains, accompanied by small earth shudders that no doubt unnerved the settlers. Some may have known what was to come, though many newcomers would be unaware of what the rumbling, shaking, earth meant. Few could have predicted the power when on that crisp, foggy, ‘hot water bottle weather’ day [22] – the 7.8 magnitude earthquake struck.

Ruth’s father, Edward Spencer Woodford, the grandfather of the small family settlement, was at work on this day. As he had done for many years, Grandfather Woodford was working alone, with only the strength in his wiry body and hand tools, repairing the road between Murchison and the city of Nelson, 120km to the north. He had built a simple one-room wooden hut on the roadside as his weekday home. In years to come he would recount that on that day as the earth began to rock and shift, he fell to his knees, bowed his head, and prayed.[3] He prayed throughout one of the strongest earthquakes in the world that year, an earthquake that remains the third most deadly recorded in NZ. [23]

This quake was so strong men covered their ears to block the deafening sounds of rocks tumbling from the mountainside. Sounds that were heard over 250km away. The earth was lifted 15 feet, raising the town of Murchison and changing the landscape forever. Homes slid off mountains with families still inside. Cattle were unable to stand. The earthquake twisted and buckled rail lines. Upturned roads were destroyed, communication links severed, and bridges washed away. Settlements were left with no communication with each other or other parts of the country.[25] [26]

Through all this Grandfather Woodford prayed and when the earth finally became still, he opened his eyes and found himself safe on a ledge of leftover road with devastation everywhere he looked. So complete was the destruction that the rest of the country did not know the impact on Murchison and surrounding settlements until the next day when groups of men walked the many kilometres out to find assistance.

It is hard to imagine looking out over a landscape so altered you cannot find familiar markers. The clench of your stomach, the trembling through your body with each rumbling aftershock – wondering if it is to begin again. Seeing the dull staring eyes of people around you. The frenetic activity of trying to put things right. The brave words scattered about: “We will rebuild” “This will not stop us” “We have done it before; we will build again”.

Ruth and husband Matthew in later years at their Nuggety Creek home.

The earthquake splintered the tiny community. In the immediate aftermath, many families were moved to less-affected towns. Some families distressed by continuing aftershocks, the destruction of a familiar landscape, and understanding the years of hard work it would take to rebuild, did not return.[28] The remaining families, including the Woodford Robinsons, came together through the shared task of rebuilding. Drawing on their resilience in overcoming obstacles, they forged a strong community in the months and years following that June day.[25]

For Ruth, her strength and resilience would soon be tested again.

Many years earlier, when Ruth was eight and Lydia was nine years old, they along with their younger siblings had shared a deep-seated grief following the death of their young mother, Euphemia Julia Woodford. This was possibly when Lydia and Ruth began to believe in omens. A belief they held (shared by some Māori people) was that a Piwakawaka (Fantail) flitting into the house signified a death coming. Three weeks after the earthquake on 9th July 1929, Ruth may have been visited by the tiny bird warning of the sudden death of her fifth child, Adeline Ruth Robinson. Adeline just 20 years of age died suddenly in Nelson Hospital.[29]

Adeline had died suddenly from Primary Pneumococcal Acute General Peritonitis. At that time a rare and fatal infection. While it remains rare today, the condition can now be treated with antibiotics that were not available to Adeline.[30] It is not known whether Ruth was with her, travel and communications between their home in Nuggety Creek and Nelson were significantly affected by the earthquake. [31] Nelson itself had suffered damage, including the hospital and the nearby college [32] where Adeline’s sister Eva, worked as a teacher.

Later in life, Lydia described how she and Ruth would wail whenever they heard of a death; the keening of a grieving mother no doubt followed Adeline’s death. Contemplating Ruth’s grief, I recalled in 2001 a mother questioning me as she struggled with the loss of her young daughter killed in an accident, while simultaneously across the world thousands were killed when planes flew into two skyscrapers in New York. “Is grief any less or different for the family when it is one, or one of thousands?” “Why is their grief shared and mourned by everyone and mine is not?” “Do they not see I relive my grief through every news report?” For Ruth, whether with her daughter or hearing the news from afar the grief was likely to also fill her with disbelief and questions. “How can this happen?” “What if I had…?” Days of feeling numbness and disbelief. Nights of tears. And an unrelenting pain that seems to emanate from the heart.

A few months after the earthquake and Adeline’s death, the third event, a crisis that would travel the world began in America. The ‘Wall Street Crash’ would soon impact the lives of the Woodford Robinson family, and much of NZ for the next ten years. For a country dependent on exporting their farm products the sudden lack of overseas markets and declining value of their goods saw ‘The Great Depression’ quickly settle on the country. [33] Unemployment increased, wages decreased, poverty, and starvation became familiar among workers and their families, including the extended Woodford Robinson family.

To survive, men often had to leave their families and trudge many miles to seek work on Government-created work schemes. Reduced wages left families with little to subsist on. All aspects of life; social, economic, and political; were changed. [34]

Into this bleak world, barely two years after Adeline’s death, Ruth would learn of the birth of her grand-niece. Rae Adeline (my mother) was born on the 18th of January 1931 and named after Ruth’s daughter. Rae was the fourth child born to Eva Naomi, (the daughter of Ruth’s older sister and confidante Lydia) and Henry Trenton Horn. A tiny olive-skinned baby with large brown eyes, a real-life doll to care for, her 11-year-old sister Marjorie thought . A joy in an era of unfathomable hardship, yet also a burden for a family barely surviving.

At this time the Horn family lived in the growing Waikato settlement of Te Kūiti, a town of 2,475 people serving as a hub for the many tourists visiting the nearby Waitomo Limestone and Glow Worm Caves, and the local farming communities. Te Kūiti sits in a valley, surrounded by heavily forested mountains, and part of the volcanic North Island region known as the King Country (Te Rohe Pōtae). The King Country had been named not after the English monarchy but after the Māori King Movement of the late 1800s. With its largely impregnable landscape and brutal winters, the area saw few European settlers until the late 19th century. [35] [36]

Throughout the years of the depression, both Māori and Europeans struggled to survive in this inhospitable region. Work became difficult to find, and wages decreased. Harry (Henry Trenton) took work where he could, often relying on others to feed and support his family.

The youngest of four, Rae Adeline had been born as the full force of the Great Depression began to take hold of families, impacting the lives of the Horn family and many others across the Waikato region and beyond. Harry, Eva and their four young children would struggle to survive through the years of the Depression.

Family stories bring to life those never-forgotten years of survival during the 1930s. Tales of a draughty, damp, home with water coming up through the floor when the river flood plain beneath them rose with the rains. Constant hunger. Meals from whatever local plants could be edible. Clothing was repaired until threadbare. The reuse of every item possible and punishment for waste. A habit of frugal living that my grandmother would continue throughout her long life.

Resilient and tenacious this family would survive the depression, and the years of the Second World War beginning to flourish in the post-war years and beyond. Ruth and her sister Lydia would remain close throughout their long lives.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

[1] Eva Florence Robinson, The Nuggety Valley A Child’s Memories. Eva Florence Robinson, 1999.

[2] Edna JAMES, Small Steps. Self published.

[3] Rae Atkins, ‘Oral Family Recollection’, 2020.

[4] ‘17 June 1929 – Murchison Earthquake | Owen River Tavern and Motel’. Accessed: Jun. 24, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://owenrivertavern.co.nz/murchison_earthquake.html

[5] ‘In the Murchison District. Goldmining’, Grey River Argus, p. 1, Apr. 23, 1910.

[6] Robson, Edward Thomas, ‘Putting His Shoulder To The Wheel’, Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections AWNS-19121017-06-04. Accessed: Apr. 29, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://kura.aucklandlibraries.govt.nz/digital/collection/photos/id/205993

[7] Theresa Gibson Collection, Leaving for the Farm. 1912. Accessed: Apr. 29, 2024. [Photo]. Available: https://www.facebook.com/MurchisonMuseum/photos/a.1311131362338657/1311103615674765/?type=3&ref=embed_post

[8] ‘Mike O’Byrne’s Central House Movers, a Bulls-based success story.’ Accessed: Jul. 29, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://contractormag.co.nz/contractor/central-house-movers/

[9] ‘Woodford Robinson Ruth Chart’. Ancestry.com.

[10] ‘Woodford Robinson Marriage 1901’. Find my Past.

[11] ‘Robinson Robert Pace Chart’. Ancestry.com.au.

[12] N. Z. M. for C. and H. T. M. Taonga, ‘Mining’. Accessed: Apr. 29, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://teara.govt.nz/en/west-coast-region/page-9

[13] ‘New Zealand Coal Mining History’. Accessed: Dec. 10, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.WikiTree.com/wiki/Space:New_Zealand_Coal_Mining_History

[14] 1871 Census England and Wales, ‘Matthew Robinson 1871 Census’. National Archives London, England. [Online]. Available: https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:VB88-H9C : Sat Feb 24 07:24:33 UTC 2024

[15] ‘The dangers of coal – roadside stories | NZHistory, New Zealand history online’. Accessed: Apr. 11, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/media/video/dangers-coal-roadside-story

[16] ‘IMAGE Denniston Incline and settlement.circa 1910`s -1920`s.’, West Coast New Zealand History. Accessed: Apr. 11, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://westcoast.recollect.co.nz/nodes/view/32646

[17] ‘Denniston Incline | Engineering New Zealand’. Accessed: Jul. 08, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.engineeringnz.org/programmes/heritage/heritage-records/denniston-incline/

[18] N. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand, ‘Denniston Incline Image’, Denniston Incline | Items | National Library of New Zealand | National Library of New Zealand. Accessed: Jul. 08, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://natlib.govt.nz/records/23024826

[19] ‘Granity | NZETC’. Accessed: Jul. 27, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-Cyc05Cycl-t1-body1-d1-d2-d30.html

[20] Ancestry.com, ‘New Zealand, Registers of Medical Practitioners and Nurses, 1873, 1882-1933’. Ancestry.com Operations, Inc. Provo, UT, USA, 2014. [Online]. Available: https://www.ancestry.com.au/family-tree/person/tree/177558046/person/262418749882/facts

[21] archives, ‘Midwifery in New Zealand, 1904-1971’, Wise Woman Archives Trust. Accessed: Dec. 10, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://wwat.nz/midwifery-in-new-zealand-1904-1971/

[22] ‘Hot Water Bottle Weather Page 2 Advertisements Column 8 , Page 2 Advertisements Column 8’, Nelson Evening Mail, vol. LXIII, p. 2, Jun. 18, 1929.

[23] ‘List of earthquakes in 1929’, Wikipedia. Mar. 30, 2023. Accessed: Jul. 09, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=List_of_earthquakes_in_1929&oldid=1147394331

[24] ‘IMAGE Morel’s house, Murchison earthquake’, Nelson Provincial Museum. Accessed: Jul. 08, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://collection.nelsonmuseum.co.nz/objects/P24627/morels-house-murchison-earthquake

[25] ‘Remembering the Murchison 17: New Zealand’s third deadliest recorded earthquake 90 years ago – NZ Herald’. Accessed: Dec. 02, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/remembering-the-murchison-17-new-zealands-third-deadliest-recorded-earthquake-90-years-ago/AHT63IZTK674U4WK4KIGRKHJ2U/

[26] Franklin Times, ‘Blessing in Disguise. Murchison Earthquake’, Franklin Times, vol. XIX, no. 142, p. 8, Dec. 06, 1929.

[27] ‘IMAGE Murchison earthquake.Nelson Photo News’, West Coast New Zealand History. Accessed: Apr. 13, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://westcoast.recollect.co.nz/nodes/view/1449

[28] ‘Anxious to Return , Restoration of Houses’, Hawera Star, vol. XLIX, p. 11, Jun. 28, 1929.

[29] Births Deaths Marriages NZ, ‘1929 Death Certificate Adeline Ruth Robinson’.

[30] E. W. Johnson, ‘PRIMARY PNEUMOCOCCAL PERITONITIS.’, Ann. Surg., Dec. 1924, Accessed: Jun. 23, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/PRIMARY-PNEUMOCOCCAL-PERITONITIS.-Johnson/df2ac65a82920f499e9bb892e01e6e4e053c5b7c

[31] ‘Communications Restored , Murchison Earthquake’, Stratford Evening Post, no. 99, p. 6, Sep. 05, 1929.

[32] ‘Papers Past | Newspapers | Nelson Evening Mail | 18 June 1929 | Page 2 Advertisements Column 8’. Accessed: Jul. 07, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NEM19290618.2.19.8?end_date=19-06-1929&items_per_page=10&query=weather&snippet=true&start_date=16-06-1929&title=TC%2cGBARG%2cMOST%2cNEM%2cNENZC

[33] ‘The Wall Street Crash Origins’. Accessed: Jun. 25, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/politics/the-new-zealand-legion/origins

[34] National Library, ‘Topic Explorer – The Great Depression in Aotearoa New Zealand’. Accessed: Jun. 25, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://natlib.govt.nz/schools/topics/62c39679ee1e3d002ae2b125/the-great-depression-in-aotearoa-new-zealand

[35] N. Not Specified, ‘Near Te Kuiti’, Near Te Kuiti | Items | National Library of New Zealand | National Library of New Zealand. Accessed: May 01, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://natlib.govt.nz/records/23045711

[36] ‘King Country region’. Accessed: Dec. 09, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://teara.govt.nz/en/king-country-region/print

[37] ‘King Country’, Wikipedia. Dec. 05, 2023. Accessed: Dec. 09, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=King_Country&oldid=1188408353

Hi Melanie,I went to Denniston with my father in my early teens on our way to meet my mother’s family in Dunedin. We stopped there as he said this was where his Grandfather, my Great Grandad Mathew Robinson ( great grandad Robbie I called him) was from. I assume it is Ruth and Robert’s first born son (and hoping so as it’s a fabulous story). Mathew was my Nana Edna’s dad and I was blessed to know and spend much of my youth visiting him until he passed at 80 years old when I was 8 years old in 1980. He moved to Huntly north island at some stage and married my great grandma Hester and I gather that he worked in the coal mines in Huntly as did his eldest son. I am researching my family ancestory when I came across this story and it has helped piece together part of my ancestral lineage. Very interesting and enlightening as my grandparents have passed now and until I do a DNA test the snippets from the internet can be time consuming figuring out who are actual ancestors from the names I have! I am sure Ruth’s first son Mathew is my gg robbie from what my dad and uncle have told me, and if you know he moved to Huntly this can confirm it for me? Thank-you from Rebecca or Becky my dad, Nana and gg robbie called me.

Hi Rebecca, I am not as familiar with the Robinson ancestry as I am descended from the Woodfords. It does sound like this is Ruth and Robert’s first born but it might need more research to confirm. My research was mainly around Adeline for the story. If I find any info I will let you know. Kind regards Melanie

Thank you so much for sending the story on ,it has filled in a lot of gaps for me and corrected some stories.

I wished I had written down some of the stories Nana Ruth Robinson and Dad had told me.I also remember Rae Atkins name and reading her letters she wrote to Mum and Dad I

Hi Raelene, Sorry this has taken so long – something happened to my website. I am so pleased you found the story useful I really enjoyed researching and writing it. Yes I wish I had talked more to my great-grandmother Lydia Ann Wilson about her early life. Still at least we are researching and recording stuff now. Kind regards Melanie