Smallpox – An Unwelcome Visitor on the Australian Goldfields

A small official piece of paper in a family history album connected Victoria Australia 1858 with 2020. In both eras, it was a disease travelling globally, an opportunist traveller following the movement of people whoever they were, and wherever they landed. The slip of paper – the legacy of a mass Smallpox vaccination on the Victorian Goldfields in Australia in the late nineteenth century [1]

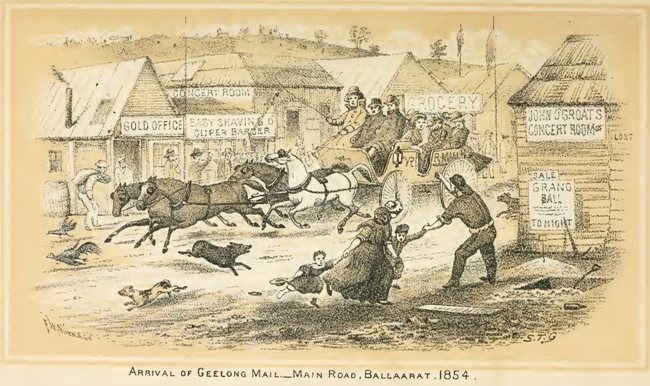

It is 1858 and people are arriving in ever-increasing numbers on the goldfields of Victoria. Families, single men, family men leaving wives and children in all parts of the globe to seek their fortune in gold. Many move globally from one gold discovery to the next.

Gold fever carried more than the hope of discovering a fortune. Travelling the globe along with the people seeking a new life were opportunistic diseases such as Smallpox. Sailors travelling the world in ships carrying goods, along with passengers crowded together enabled diseases to travel quickly from one port to another.[2]

Life on the goldfields created perfect conditions for Smallpox. As the population expanded conditions become increasingly crowded. Tightly spaced and living in tents, or simple single-room dwellings built from logs and canvas – with whole families often living in one room. Spread by person to person contact – by breath and saliva – Smallpox thrived on overcrowding and poor ventilation.[2]

Further aided by poor hygiene, the lack of sanitation, and also by-products of gold-mining itself the latter causing poor drainage and “Ground pollution from privy cesspits” [2] The conditions were perfect for transmission of a feared and fatal disease. Yet despite this people, continue to arrive from all over the world – some already carrying the disease. (2)

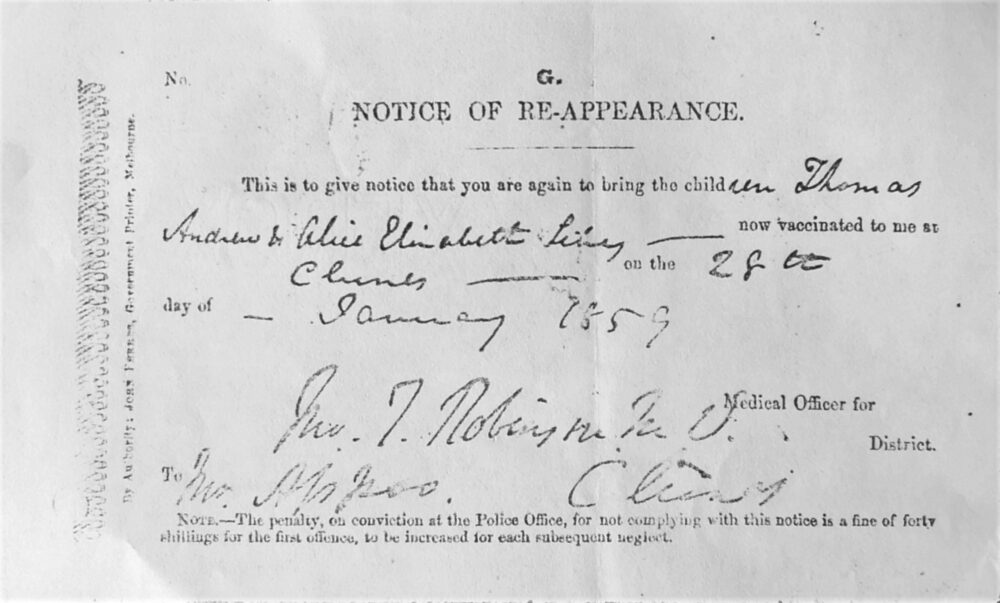

The government of Victorian responded by attempting to control the outbreak with the quarantining of infected ships [3] and the mandating of vaccination for children. Parents who refused to bring their children in were summoned to appear in court [4] and could be fined 40shillings – a hefty fine equivalent now to £320 (approximately). [5]

Mandatory vaccination presented a dilemma of supply – in the 1850s the vaccine to prevent smallpox was a live vaccine inserted into a scratch. This material had to be transported from England to the goldfields on ships – and be kept viable – a journey that could take months.

A tragic solution was developed to maintain the supply of live vaccines for the long voyage. Children – orphans – were gathered in the UK and transported – described as “human test tubes” [6]. As the voyage progressed the children were infected with smallpox material, a couple of children at a time. The hope was, there would be children alive, and with infected material that could be harvested once the ship docked in Australia.[6]

This human lymph was distributed to Victorian country areas poignantly “on glass wrapped in moist paper and oiled silk”.[2] and inserted into a scratch under the skin. To ensure supply – in addition to these government-supplied vaccines, Vaccinators would also use lymph taken from children on the goldfields, they had vaccinated previously.

Born in New Zealand, Alice Elizabeth Appoo now 14months old, and Thomas Andrew Appoo, a little over 2years old, arrived on the goldfields in Clunes with their parents Jacobus and Alice. Arriving sometime in 1858 or early 1859 from the Nelson goldfields in New Zealand.

Alice and Thomas were required to have the mandatory vaccination and then return to the Vaccinator / Doctor 8 days later to have the vaccination site checked. It is at this time the Doctor might also take samples to be used as vaccines for other children.

Confirmation that the children had been vaccinated was assured with the finding of a small slip of paper, oddly titled “Notice of Re-Appearance”. The form listed the names Alice Elizabeth and Thomas Andrew and was addressed to Mr or Mrs J. Appoo. The formal notice states “This is to give notice that you are again to bring the children … now vaccinated to me at Clunes on 28th January 1859”. Signed by the Medical officer Dr T Robinson for the Clunes district.

This small piece of paper was a find my mother had made – before the advent of internet research – seeking evidence in times when visiting record offices; scrolling through papers and microfiche was the means to discovery. The slip of paper provided a thread to link an elusive ancestral chain of movement around the world. Here were the names of two small children matching records already held, and Jacobus Appoo, the elusive ancestor who was the focus of my mother’s research.

At the time of discovery, this record had been noted excitedly as providing date, time, and place. It raised further (still unanswered) questions to pursue as to how and when the family moved from New Zealand to Victoria. The reason the form itself existed was unexplored and unexplained.

Further information on the children and their vaccination has not survived, or not been found. Alice Elizabeth lived to her 70s so must have developed a resistance to the many diseases and accidents that could occur. Of Thomas Andrew, no record (living or dead) has been found since this mention.

Smallpox was eventually declared to be eradicated from the world in 1980. The earliest incidence had been found in early Egyptian times – a 3,000-year history.[7] The increase of travellers moving around the world to parts where Smallpox was previously unknown had a devastating effect on local populations as well as the travellers themselves. [8]

This small official piece of paper had come to mind as the Covid-19 pandemic spread across the world in 2020. In both eras, it was a disease travelling globally at a rapid pace. Both diseases similarly affecting peoples of all cultures and all parts of society – though preferring the poor and the vulnerable. This 2020 pandemic giving time to reflect on where family history meets world history, and where the stories arising link the past with our present.

The link above offers a discussion between Natalie Pithers of Genealogy Stories and Sylvia Valentine discussing smallpox and inoculation in this episode of #TwiceRemoved. “What was smallpox? How deadly was it? How did inoculation develop and what was the reaction to it being made compulsory? How did the authorities try to enforce inoculation and how did our ancestors react to this?”

BIBLIOGRAPHY

[1] R. McWhirter, ‘“Lymph or Liberty”: Responses to Smallpox Vaccination in the Eastern Australian Colonies’, PhD, University of Tasmania, 2008. Accessed: Sep. 29, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://eprints.utas.edu.au/8077/

[2] Cousen Nicola, ‘“The Smallpox on Ballarat” | PROV’, Public Record Office Victoria Collection | PROV. https://prov.vic.gov.au/explore-collection/provenance-journal/provenance-2018/smallpox-ballarat (accessed Aug. 21, 2021).

[3] B. Huf and H. Mclean, ‘Epidemics and pandemics in Victoria: Historical Perspectives, p. 40.

[4] ‘Smallpox Prosecutions’, Age, Melbourne, Victoria, Oct. 23, 1857. Accessed: Aug. 27, 2021. [Online]. Available: http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article154832340

[5] T. N. Archives, ‘The National Archives – Currency converter: 1270–2017’, Currency converter. https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/currency-converter/ (accessed Oct. 11, 2021).

[6] E. M. Grahame, ‘Orphan children as human Petri dishes: The unorthodox fight against smallpox in 1850s Australia’, ABC News, May 27, 2020. Accessed: Aug. 21, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-05-27/ballarat-1850s-goldrush-smallpox-vaccine-quarantine/12272106

[7] ‘History of Smallpox | Smallpox | CDC’, Feb. 21, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/smallpox/history/history.html (accessed Aug. 20, 2021).

[8] ‘Smallpox Epidemics in Victoria’, Museums Victoria Collections. https://collections.museumsvictoria.com.au/articles/16882 (accessed Aug. 20, 2021).