A Tale of Two Florence Nightingales

Two Florence Nightingales; one an ancestor and one a hero of mine set me on a path of discovery. The tantalising carrot dangling before me was a hand-me-down family story that the two Florences were related. The meandering search that followed concluded with an ancestor unveiled and a hero fallen.

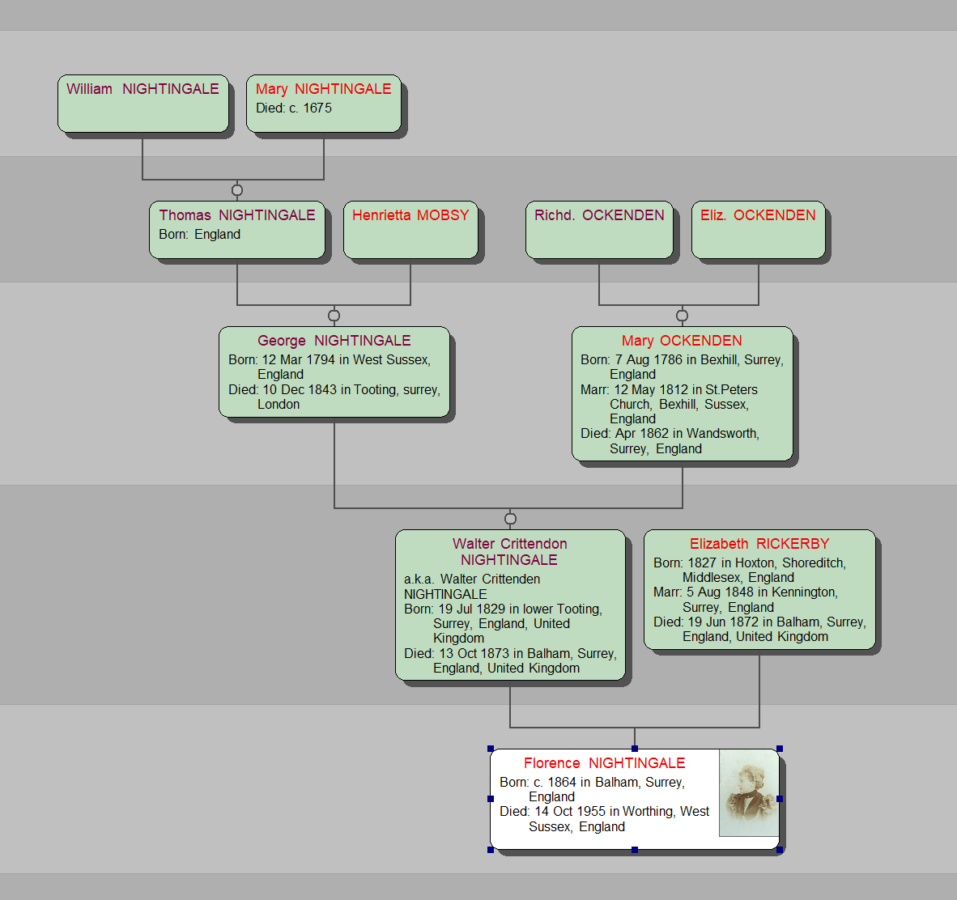

There were murmurings that Florence Nightingale in our family tree and THE Florence Nightingale were the same person. A hand-scribed, fading wall chart of the Nightingales hung forgotten in a dark corner of our family home promoted this view. Glued to the corner was a faded newspaper article headed “The Lady with the Lamp” said to highlight the family link to Florence Nightingale, marked with a red star. Wishing it to be so had prevented my examination of the chart until now when simple research revealed they could not be the same person. Florence Nightingale on the chart was born in 1864 in Tooting, Surrey, England,[1] while THE Florence (Shore) Nightingale was born in 1820, in Florence, Italy.[2] This did provide a starting point to research both Florence Nightingales.

A second family whisper was that the fathers of each Florence were first cousins. This again appeared to require a simple piece of research, yet a quick search of each family showed an abundance of Nightingales, most with large families and similar first names. Florence emerged as a popular name through the 1800s with the birth of at least 56 ‘Florence Nightingales’ registered from 1837 to 1864 in England [3].

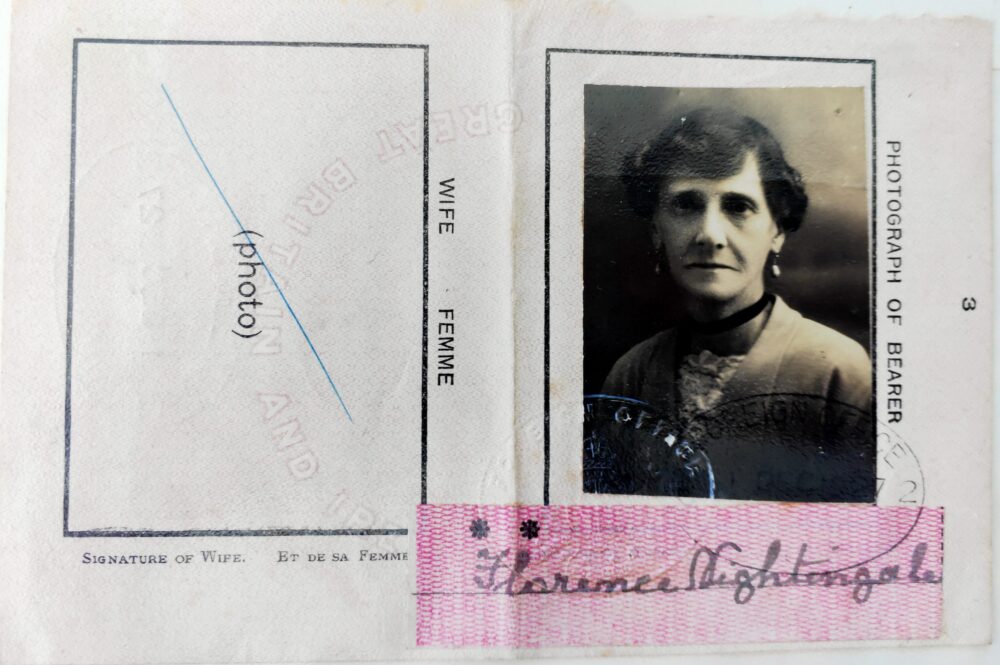

There were similarities between the two Florences; both lived until 90 years of age as single independent women. Both stayed close to family throughout their lives, each had a close relationship with their sister. The two Florences travelled extensively; Florence Shore Nightingale was born abroad in Italy while Florence travelled later in life including time spent studying singing in Munich – possibly at the same time as her dear sister Minnie Kate studied piano.

There were also differences – born in 1864 Florence Nightingale was the 9th of 11 children, her sister Minnie Kate was born barely one year later. Florence Shore Nightingale had only one sibling – sister Frances Parthenope Cope, a year younger than Florence. Florence worked for a time as a Governess [4] while Florence Shore Nightingale is credited with developing modern nursing.[5] Family life was different; for Florence Nightingale both parents died within a year of each other when Florence was 8 years old, followed a year later by her 21-year-old brother William who had been charged with looking after the family. Florence Shore Nightingale’s parents were wealthy and lived until Florence was an adult, providing her with opportunities and education.

Florence, like me, felt a strong connection to Florence Shore Nightingale. An obituary for Florence Nightingale after her death in 1955 alluded to her delight in two childhood meetings with “her heroine”, once not long before Florence Shore Nightingale died. Florence had made significant donations to the Florence Nightingale Hospital, her last request was “No flowers, no mourning, her wish a donation if desired to Florence Nightingale Hospital N.W.1” I was cautiously excited to read Florence had reported the two fathers were cousins. [6] yet without proof, it would remain no more than a tantalising hint.

Without proof of an ancestral connection with Florence Shore Nightingale, my link would remain a bond through a love of nursing. Becoming a nurse had been my ambition for as long as I remember. Throughout my life I had been drawn to reading about the women who had carved that nursing path, seeking out the heroes I could hang my imagination on. The nurses who worked in war zones; in remote places with no help but their wits; those who developed life-changing techniques. Florence Shore Nightingale, was often the subject of the books read in early years and an ancestral link with such a hero would be too good to be true.

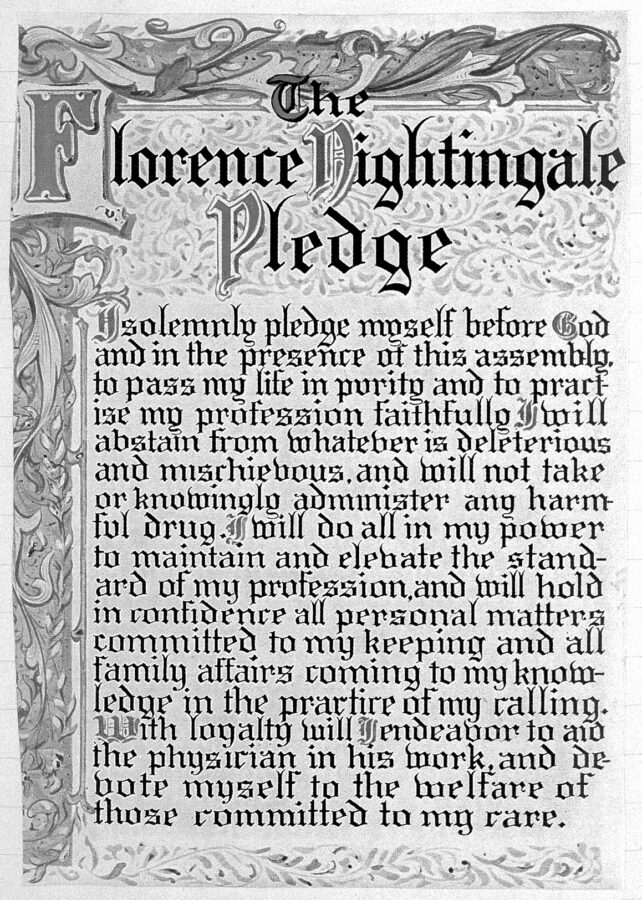

Whether or not we were related Florence Shore Nightingale influenced my own early nursing career. New Zealand adopted the Florence Nightingale model for nursing from the late 1800s to the late 1970s. At the time I finished my nursing training change was on the horizon – long gone was the vow of purity, the requirement to obey and not question the doctor was diminishing. Florence Shore Nightingale was known to have opposed government intervention in nursing management and would have disagreed with the NZ government’s registration of nurses and nursing training [7]pg71 believing control of nursing should be with nurses. Through the 1970s growing voices advocated university-based education yet they were battling the strong foundation described as the “Nightingale ethos of training” [7]. My nursing training ‘on the job’ in a hospital was steeped in the way of Florence Nightingale.

Image L0008728 (2018-04-01):

As I reminisced I recalled a folder about Florence Shore Nightingale compiled in the 1980s by a nursing colleague who shared my love of nursing and its heroes. As I searched for the folder I recalled John Wilson, the gentle, softly-spoken colleague who had compiled it. A nursing historian with an interest in the work of Elizabeth Kenny and Florence Nightingale, John had completed extensive research, published papers, and taught nursing history yet now I could find no trace of him. I did find the simple plastic folder containing various snippets of his findings labelled in his bold calligraphy script – ‘Florence Nightingale’.

The folder contained genealogy charts helpful in understanding the various strands of Florence Shore Nightingale’s family. Florence Nightingale’s father was William Shore, the Nightingale name was bestowed later, upon receiving an inheritance from his uncle – Peter Nightingale of Lea, Ashover. Peter had no children suggesting that any possible connection was more likely with Peter Nightingale’s sister Ann. Ann Nightingale had married a man with an even more common last name Evans: George Evans. It appeared coincidence that both had fathers named William – William Crittenden Nightingale was my ancestor’s father.

As I contemplated the curated folder of information I recalled my excitement over a visit to the Florence Nightingale Museum in London a few years earlier. Long after my Nursing career had ended, my fascination with Florence continued. It had been a chilly bleak winter’s day, with a biting wind whipping rain and debris across my path as I sought the entrance to the small museum, tucked under the stairs in the St Thomas Hospital precinct. The cheery warmth inside revealed rooms that seemed filled with young women who, in my imagination, were eager new nurses, and older had-once-been-nurses. Women vying for viewing time in the small collection showcasing Florence Nightingale’s life and work.[8]

Here I first learned of the work of Mary Seacole.[9] A woman from Jamaica who funded her own nursing and care facilities throughout her life, moving to England and on to Crimea. There was contention about the level of influence Mary Seacole had on nursing and views were divided on whether her work in Crimea had been equal to that of Florence.[10].

Recalling this visit I sought more information about the work of Mary Seacole vis a vis Florence Nightingale. My warm reverie was interrupted by an article headed “The Racist Lady with the Lamp”. Reading the article, further words were pushing forward that I had never wished to associate with my hero: Racist, Colonialist, Imperialist. Reluctantly I read on finding descriptions suggesting racist views towards indigenous peoples. Of having lived a privileged life in full support and promotion of the British Empire.[11]

This was a woman who had looked at me daily from a framed print in my office. Here was a conundrum family historians describe. What do you do when you find unpalatable information? I had expected to find challenging events and actions in the ancestors gathering on an ever-expanding tree, I had not considered it would happen to a hero of mine such as Florence. How do I manage this confusion over, and confrontation of such previously undiscovered views?

A dialogue of chatter began in my head between the hero worshipper (HW) and the researcher (R):

HW That is in the past. We are judging Florence Nightingale based on our current beliefs and values, these have evolved with time. It was different back then. It is reported some of her views would be considered racist now, but surely her attitudes matched her contemporaries.

R Does not being aware of it then, make it right now? What if it was human trafficking or slave trading? Surely equality and humanity would prevail. And not everyone did think in that way, there were those who thought differently, who fought for the rights of first nation peoples.

HW Florence did so much for nursing and for women, couldn’t we just accept that? After all, she is credited with being the pioneer of modern nursing.

R You want to accept all of it! Would you be happy following her edict nurses always obey doctors? Or the insistence a good nurse must also be a good woman, embodying cleanliness of morals and of body and surroundings.

HW Maybe I have read too many shiny biographies and not examined her life, but she did revolutionise nursing practice and contribute to the development of a public health system.

R Florence believed strongly in the expansion of the British Empire with its “inestimable blessing of civilisation” Through this lens it is suggested Florence believed the decline of indigenous people was due to deficits in their populations and lifestyle [11] others view it as the language of the time and Florence’s desire to obtain what she believed was good public health management for all, including indigenous populations in the countries Britain was colonising.[12]

HW That was how people thought and acted in Victorian times what else could she do?

R Mmmmm not everyone behaved in that way for example in Victoria Australia in the 1850s the Legislative Council stated the belief that the responsibility for the decrease in the Aboriginal population was the occupation of the lands by white people.

HW I am so confused and conflicted this was Florence Nightingale my hero – should I now leave my hero behind?

R No, but maybe we should be looking more critically at our heroes. We could approach with a more open mind to consider Florence Nightingale and other heroes in a more balanced way – their achievements and their flaws, we might help break down what continues to be “historically persistent structural barriers”.[13]

Maybe Florence can still be my hero albeit with awareness and openness of her flaws and unpalatable views and the impact those views had on others, particularly first nations populations.

Conflicting thoughts were whirling about when I returned to the safe ground of my original task – linking Florence Nightingale, daughter of Walter Crittenden Nightingale and Mary Ockendon with THE Florence Shore Nightingale daughter of William Shore Nightingale and Frances (Fanny) Smith. I created a laddered chart between them. After many hours of sifting through the repetitive first names and trying to match the many Nightingales I conclude this story has no end. I have learned much about both Florences and discovered more information about our ancestor Florence Nightingale.

I am left without discovering a link between the two Florences, and with an ongoing dialogue of what it means when ancestral behaviour or actions are contentious or unpalatable. Throughout this journey of discovery and questions I have gained a strong appreciation of the learning family history and its intersection with social and world history can offer.

BIBIOGRAPHY

[1] Ancestry.com, ‘Florence Nightingale – London, England, Church of England Births and Baptisms, 1813-1923’, London, England, Church of England Births and Baptisms, 1813-1923, 1864. https://www.ancestry.com.au/imageviewer/collections/1558/images/31280_195202-00401?pId=2170734 (accessed May 19, 2023).

[2] ‘Florence Nightingale, “England Births and Christenings, 1538-1975” • FamilySearch’. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:CFL8-GMPZ (accessed May 19, 2023).

[3] BDM FreeSearch, ‘Florence Nightingale 1837 to 1864’, BDM FreeSearch. https://www.freebmd.org.uk/cgi/search.pl (accessed May 19, 2023).

[4] ‘1891 England, Wales & Scotland Census Image | findmypast.com.au’. https://search.findmypast.com.au/record?id=GBC%2F1891%2F0455%2F0053&parentid=GBC%2F1891%2F0003848868 (accessed May 19, 2023).

[5] ‘(26) Florence Nightingale: The Mother of Modern Nursing | LinkedIn’. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/florence-nightingale-mother-modern-nursing-brian-hadi-attarbashi/ (accessed Mar. 14, 2023).

[6] ‘Worthing’s Florence Nightingale Dies Aged 91’, Worthing Herald, p. 1, Oct. 21, 1955.

[7] Elaine Papps, ‘KNOWLEDGE, POWER, AND NURSING EDUCATION IN NEW ZEALAND: A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF THE. CONSTRUCTION OF THE NURSING IDENTITY.’, Doctoral Thesis Philosophy, University of Otage, Dunedin, New Zealand, 1997. Accessed: Mar. 14, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://ourarchive.otago.ac.nz/bitstream/handle/10523/6446/PappsElaine1997PhD.pdf?isAllowed=y&sequence=2

[8] ‘Home – Florence Nightingale Museum London’. https://www.florence-nightingale.co.uk/ (accessed May 19, 2023).

[9] admin, ‘Mary Seacole – Florence Nightingale Museum London’, Oct. 21, 2019. https://www.florence-nightingale.co.uk/mary-seacole/ (accessed May 19, 2023).

[10] ‘Mary Seacole’. https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/mary-seacole (accessed May 19, 2023).

[11] ‘Kai Tiaki Nursing New Zealand April 2020 by New Zealand Nurses Organisation – Issuu’, Apr. 08, 2020. https://issuu.com/kaitiaki/docs/kai_tiaki_april_2020 (accessed Mar. 03, 2023).

[12] ‘Sanitary Statistics of Native Colonial Schools and Hospitals, by Florence Nightingale; A Project Gutenberg eBook.’ https://www.gutenberg.org/files/52653/52653-h/52653-h.htm (accessed May 19, 2023).

[13] P. D’Antonio, ‘What do we do about Florence Nightingale?’, Nurs. Inq., vol. 29, no. 1, p. e12450, 2022, doi: 10.1111/nin.12450.