Great Aunt Ada

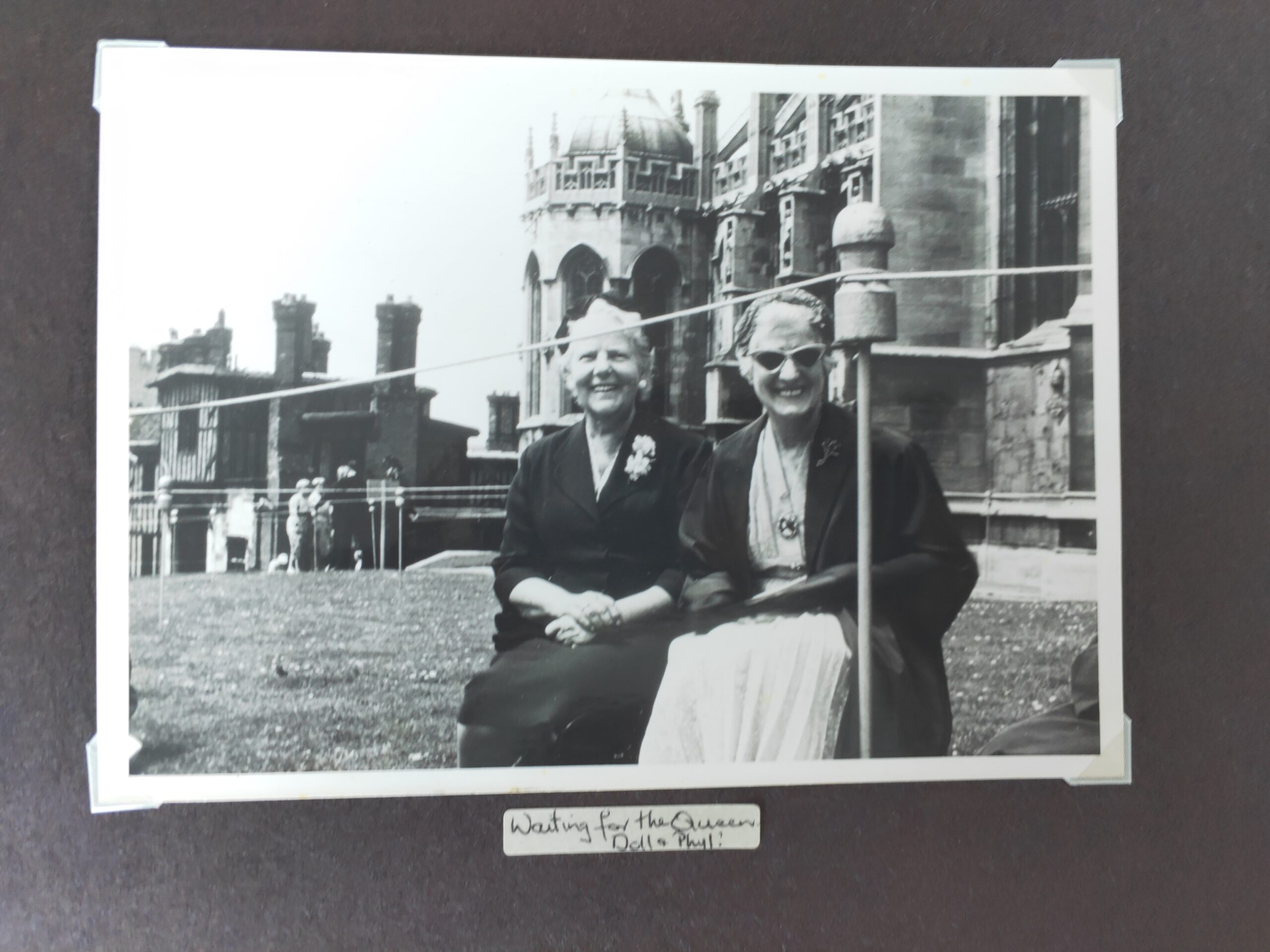

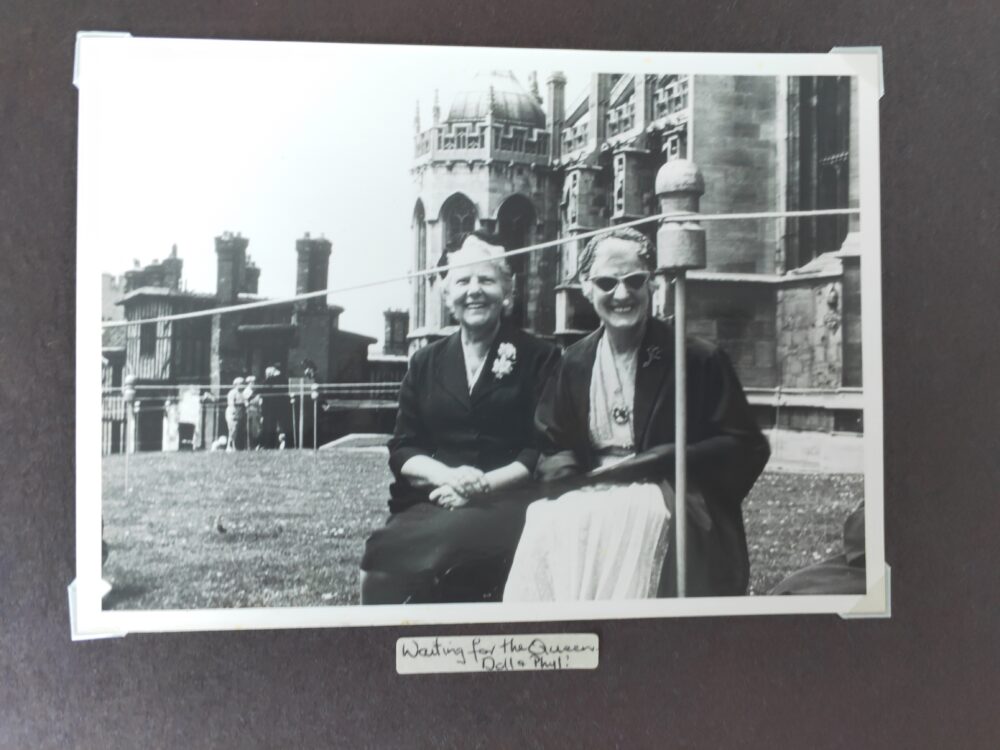

The life of Great Aunt Ada seemed more deserving of a best-selling biography than the tiny snippets of her life my research had uncovered. Without a published memoir it seemed the story of Ada Constance Atkins (Doll), needed to be told. Her loving and proud nephew, Frederick John Michael Champion (Champ), lit the spark to investigate her life. Champ, the son of Doll’s oldest sister, had a passion for family stories. It was his admiration of Doll, and his gift to me of her necklace of small milky green beads that drew me to learn more.

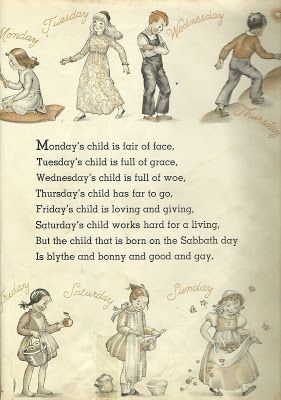

If there was a memoir to be published, I believe the title “Thursday’s Child” would be a perfect reflection of Ada’s life. “Thursday’s child has far to go” [1] reads the line from the fortune-telling poem. It suggests a child born on this day would achieve much in life. Born on a Thursday, the 14th of December 1893 Ada Constance Atkins did just that.

A biography would also need a tantalising dust cover synopsis:

‘’This biography tells the story of the remarkable life of Ada Constance Atkins born into poverty at the end of the nineteenth century, the seventh of nine children. Ada was born before women in England could vote and died in the early days of the 1960s Women’s Liberation Movement. Over her life she witnessed two World Wars; worked for President Juan Peron of Argentina; rose to a valued position in what was traditionally a male workforce; and was instrumental in introducing new technology to businesses in the United Kingdom. All of this was achieved at a time when women had little power and while facing her own significant challenges and family tragedies.”

A survivor from the beginning Doll was born on a chilly mid-December day, with an influenza pandemic causing illness and death swirling around London. This pandemic had begun in Russia some years earlier and spread out along the growing rail network connecting Europe and England [2]. Doll’s sister, Mary Hyacinth (Hyttie) would die from this new disease a few years after Doll’s birth. Hyttie came home from work complaining of feeling unwell and died five days later of Influenza.

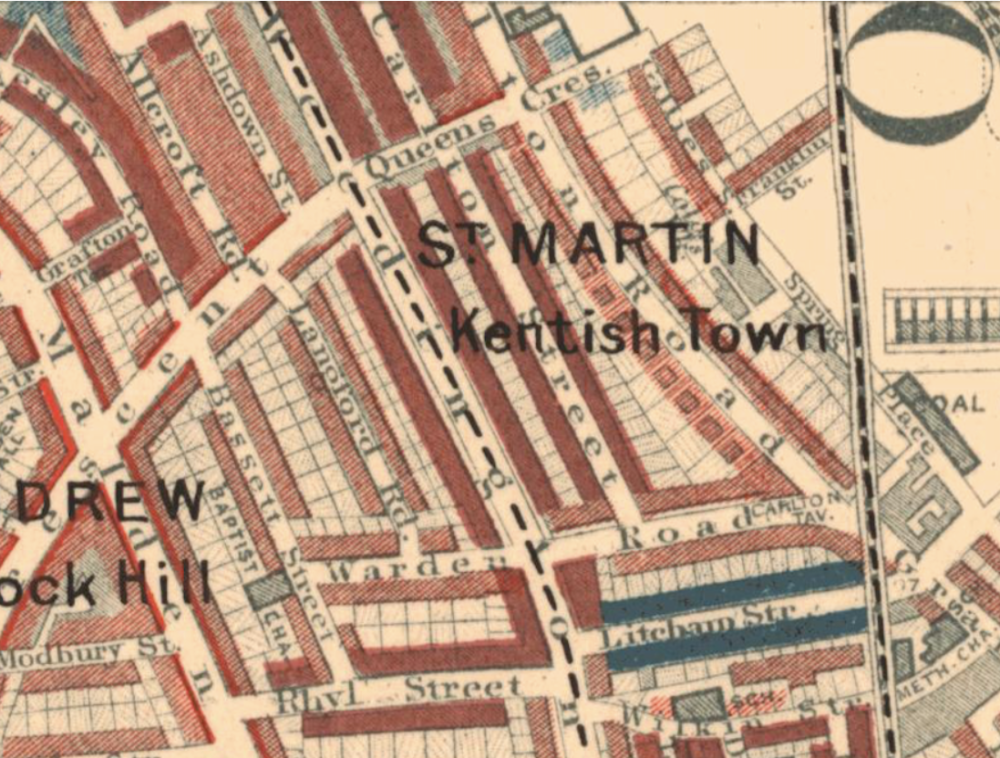

Knowledge of Doll’s early years are scant, the family moved frequently, and her father James Michael worked a range of jobs including shopman, wood chopper[3] and grocers assistant,[4] possibly to support his expanding family and establish himself in the grocery business. Early accommodation was in Litcham Street, Kentish Town, a street with a less than savoury reputation[5]. Charles Booth mapped London in 1889 according to levels of poverty[6]. Standing out on the colour-coded map of Kentish Town, amidst the vast swathe of red (middle class) streets are several coloured dark blue denoting significant poverty at the centre is Litcham Street. The family moved from here in the early years of the 20th century, it may have been due to the forced “slum clearances” but records of the clearances are few.[7]

Once James Michael had established himself as a Grocery Manager[8], and Doll and her siblings were working, the family situation began to improve. By the time she was 17 years old, Doll was working full-time in the accounts department at Marconi’s Wireless Telegraph Company. The story is told that her manager called Doll into his office to meet a visitor, a businessman from America, who was looking to recruit someone to train staff and expand sales of the new Comptometer machine being introduced in England.

Colloquially described as “a machine gun of the office”[9] the machine could make calculations at a speed previously unheard of. Developed and patented in the United States in 1887, the Comptometer was the “first commercially successful key-driven mechanical calculator.”[10] Operated in a similar way to the later electric adding machine the Comptometer was housed in a wooden box with keys on a sloping top and a lever on the side.

At this first meeting, Doll was asked if she would be interested in training staff in this advanced technology, thus beginning her new and lifelong career. Over the following years, the Comptometer was introduced to business houses throughout England, with Doll successfully training staff and assisting in the expansion of machine sales.

A new opportunity arose for Doll when the British-owned rail company ‘Buenos and Great Southern Rail’[11] in Argentina became interested in purchasing the machine. With this sale was a condition that Doll remained with the rail company, once accepted Doll began working with the company at River Plate House in London.

At that time River Plate House was a centre for businesses working in South American countries, including the vast network of British-owned rail companies.[12] This gently curving, early 20th-century building stood elegantly on the street front in Finsbury Circus. More recently, in 2014, the building was demolished amidst controversy to make way for a modern development.[13]

The history and significance of the area in South America after which River Plate House was named have diminished over time. When built in 1901 the naming of the building demonstrated the importance of British interests in South America in the 18th and 19th centuries. Rio de la Plata (River Plate) is an unusually wide estuary that was vital for shipping and connecting with the South American rail networks.[12] In 1939, River Plate came to public attention during WWII when it was the site of a battle and the first naval victory for the allies.[14]

At the outset of World War II with the fear of bombing raids across London, Doll and other River Plate House staff were evacuated to Hardwick House in the countryside of Oxfordshire.[15] Doll remained at this large Tudor house on the banks of the river Thames Hardwick House for the duration of the war. The only Comptometer operator, Doll worked alongside other British Argentina Railway staff along with Hardwick house and farm staff. [16]

At war’s end, Doll could return home to London and work at River Plate House. Further change was to follow when in 1946 a new Argentinian President was elected. Two years later President Juan Domingo Peron nationalised the British-owned railways in Argentina and closed all London office.[17] All operations were moved back to Argentina except for a small number of key personnel – including Doll – who remained in River Plate House. Doll became the Accounts department manager and worked at River Plate House until she retired.

While there are brief records of Doll’s working life there remains little detail of her personal life and the challenges she faced. Prior to the war Doll had been diagnosed with breast cancer and had had surgery; a Radical Mastectomy. This surgery was extensive, disfiguring, and often left lasting disability. When defending the extent of this surgery Dr Halsted, the surgeon who devised it stated: “After all, disability, ever so great, is a matter of very little importance as compared with the life of the patient.” [18] At that time there was no ability to grade the severity or types of tumours. Fortunately, Doll was able to return to work and life, suggesting she could apply herself to a tough and painful exercise and rehabilitation regime to ensure her recovery.

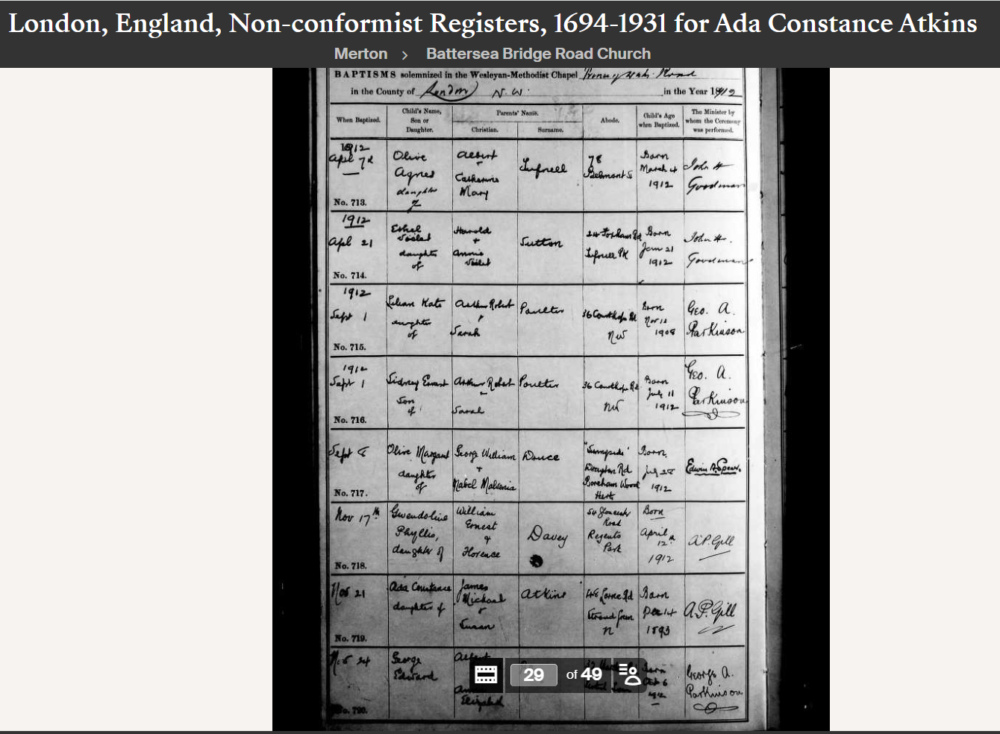

Facing her own cancer Doll would likely also have been thinking of her sister, Marion Beatrice (Beattie). Beattie died of cancer in 1912 at 30 years of age. A few months after Beattie died 19-year-old Doll was baptised in the Wesleyan Methodist Church [19].

Following her survival of breast cancer, and during her time in Oxfordshire in the second world war Doll became a Christian Scientist remaining so until she died. Doll hinted to her family in later years she was atoning for her sins earlier in life. Christian Science seems an unsurprising choice for Doll, a church suited to strong women. Begun in the United States the movement encouraged strong independent thinking women [20]. Founder Mary Baker Eddy was a strong woman, who overcame prejudice and obstacles to expand her knowledge and beliefs. Mary said her father was “taught to believe that my brain was too large for my body and so kept me much out of school”[21] yet Mary flourished. When asked why she never married Doll would quip that all the young men had been killed off during her ‘catching days’, during World War 1. There were men interested, Champ recalled an American businessman Mr Aspinall, who worked closely with Doll and assisted her brother John Francis and possibly her father to find work at the Burroughs Adding Machine Company. “Mr Aspinall may be the person cited in the 1925 case Burroughs Adding Machine Ltd v Aspinall (1925) 41 TLR 276 C.A. Yet Doll remained single and close to her family and friends.

Unusually for a single woman, when Doll died in 1966 she left a significant financial legacy of £19,446 legacy (approximately £278,000 today) [22], this seemed to further reinforce Doll was an independent woman; leaving a legacy amassed over her working lifetime; not owned by, or provided for, by a husband.

When beginning to research the story of Great Aunt Ada one of the triggers had been a curiosity to discover the history of the unusually pale milky green beads that had been gifted to me. I visited a jeweller who declared them South American Jade. There is no record of Doll visiting South America and no family story providing a clue as to how Doll came to have the beads, probably a link to her work for a South American company. The beads remain a link to my past and to the stories of Doll’s life.

Recording Doll’s story has been a reminder that everyone has a tale to tell, one that can be uncovered even without a best-selling biography. What I discovered about the unrecorded life of Ada Constance (Doll) Atkins suggests a strong and independent woman who lived life on her own terms. A true Thursday’s Child.

I am proud to call her my ancestor and grateful for the recollections recorded of her life and that of her siblings, by her adoring nephew.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

[1] ‘Monday’s Child’, Wikipedia. Jan. 24, 2023. Accessed: Jan. 28, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Monday%27s_Child&oldid=1135388987

[2] ‘The Influenza Epidemic. , the Influenza Epidemic.’, Auckland Star, vol. XXIV, no. 296, p. 5, Dec. 14, 1893.

[3] ‘James M Atkins, “England and Wales Census, 1901” • FamilySearch’. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:X9ZQ-FRD (accessed Feb. 13, 2023).

[4] ‘James M Atkins, “England and Wales Census, 1891” • FamilySearch’. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:Q3X3-7W2 (accessed Feb. 13, 2023).

[5] WESTKENTISHTOWN, ‘Litcham Street and Carlton Street’, West Kentish Town, Nov. 08, 2019. https://westkentishtown.org/2019/11/08/litcham-street-and-carlton-street/ (accessed Jan. 29, 2023).

[6] Local History Camden Town, ‘Booth Map 1889 – London Topographical Edition 1984’. https://www.locallocalhistory.co.uk/booth-map/index.htm (accessed Jan. 29, 2023).

[7] ‘Life in 19th-century slums: Victorian London’s homes from hell’, HistoryExtra. https://www.historyextra.com/period/victorian/life-in-19th-century-slums-victorian-londons-homes-from-hell/ (accessed Jan. 28, 2023).

[8] ‘James M Atkins, “England and Wales Census, 1911” • FamilySearch’. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:XW4N-8TH (accessed Feb. 13, 2023).

[9] ‘Comptometer Books and Manuals – Jaap’s Mechanical Calculators Page’. https://www.jaapsch.net/mechcalc/comptometer_books.htm (accessed Feb. 13, 2023).

[10] ‘Comptometer – Wikipedia’. https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Comptometer (accessed Jan. 28, 2023).

[11] ‘Buenos Aires Great Southern Railway | Science Museum Group Collection’. https://collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk/people/ap26873/buenos-aires-great-southern-railway (accessed Feb. 13, 2023).

[12] ‘The River Plate – Shipping Wonders of the World’. https://www.shippingwondersoftheworld.com/river_plate.html (accessed Jan. 28, 2023).

[13] eddyoc, ‘R.I.P. River Plate House’, The destruction of London, May 12, 2014. https://londondestruction.wordpress.com/2014/05/12/r-i-p-river-plate-house/ (accessed Jan. 28, 2023).

[14] ‘Battle Of The River Plate | NZHistory, New Zealand history online’. https://nzhistory.govt.nz/keyword/river-plate (accessed Jan. 28, 2023).

[15] ‘Hardwick House, Oxfordshire’, Wikipedia. Jan. 11, 2021. Accessed: Feb. 05, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Hardwick_House,_Oxfordshire&oldid=999688995

[16] Ancestry, ‘1939 England and Wales Register’. https://www.ancestry.com.au/imageviewer/collections/61596/images/tna_r39_2210_2210g_004?pId=1886571 (accessed Jan. 28, 2023).

[17] ‘Railway nationalisation in Argentina’, Wikipedia. Dec. 03, 2022. Accessed: Feb. 13, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Railway_nationalisation_in_Argentina&oldid=1125367626

[18] ‘The history of breast cancer surgery: Halsted’s radical mastectomy and beyond’, Australian Medical Student Journal. https://www.amsj.org/archives/3019 (accessed Jan. 26, 2023).

[19] ‘Baptism Ancestry.com.au – London, England, Non-conformist Registers, 1694-1931’. https://www.ancestry.com.au/imageviewer/collections/1906/images/31846_213204-00421?pId=132537 (accessed Feb. 13, 2023).

[20] ‘Women of History Archives’, Mary Baker Eddy Library. https://www.marybakereddylibrary.org/research/category/women-of-history/ (accessed Feb. 13, 2023).

[21] T. M. B. E. Library, ‘“Friendship” by Hugh Black’, Mary Baker Eddy Library, Sep. 02, 2010. https://www.marybakereddylibrary.org/research/friendship-by-hugh-black/ (accessed Feb. 13, 2023).

[22] ‘Inflation calculator’. https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/monetary-policy/inflation/inflation-calculator (accessed Jan. 28, 2023).

[23] ‘1889–1890 Influenza Pandemic’, Wikipedia. Dec. 30, 2022. Accessed: Jan. 23, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=1889%E2%80%931890_pandemic&oldid=1130412533

[24] ‘Aspinall vs Burroughs JournalsOnlinePDF.pdf’. Accessed: Feb. 13, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://journalsonline.academypublishing.org.sg/Journals/Singapore-Academy-of-Law-Journal/e-Archive/ctl/eFirstSALPDFJournalView/mid/495/ArticleId/557/Citation/JournalsOnlinePDF

[25] ‘BRITISH ENTERPRISE IN SOUTH AMERICA’. http://mikes.railhistory.railfan.net/r088.html (accessed Jan. 28, 2023).

[26] ‘Monday’s Child – Nursery Rhymes’. https://allnurseryrhymes.com/mondays-child/ (accessed Jan. 28, 2023).

[27] ‘Weather 1893 dec 16 guardian – Newspapers.com’, The Guardian. file:///C:/Users/atkin/Zotero/storage/WYY7LY5M/1893-dec-16-guardian.html (accessed Jan. 28, 2023).