Jane Slow: Karori Asylum and Her Final Years

The only remaining traces of Jane Slow are attachments to records of men. Jane is an addendum to history, with no researcher avidly seeking Jane’s history and no children who passed on her story. History has buried stories of many women. So many strong, resilient, resourceful women who were historically invisible, with no political record, and no part in the political process.

This piece is to give a voice to one such woman, an ancestor of mine: Jane Slow. But this relies on my imagination wound around sparse facts clipped from other’s histories. This part of her story begins on the 10th January 1866: the day Jane’s life changed forever.

“I well remember that day. It was one of those New Zealand summer days—not hot but warm, sticky, and hard to keep fresh. The sky was covered with the familiar thick, white, moving clouds that seem to cover the whole country when you look up. I was befuddled after a long, difficult journey from home in the Wairau. I was tired, I was anxious to go back home.

Confusion clouded my mind as I tried to understand what had bought me to this. Where was Frederick, my husband of just five years? Why had I been taken so far from the home Frederick and I had made in the Wairau Valley? Just when I had got used to it being so far from everything. I had even come to appreciate the wild, tangled green-black bush looming large around our acres of farmland. I had not gotten used to the Māori men who appeared every so often, they looked so proud and fierce, in their own dress and with all their tattoos they still scared me, but it was all part of home now.

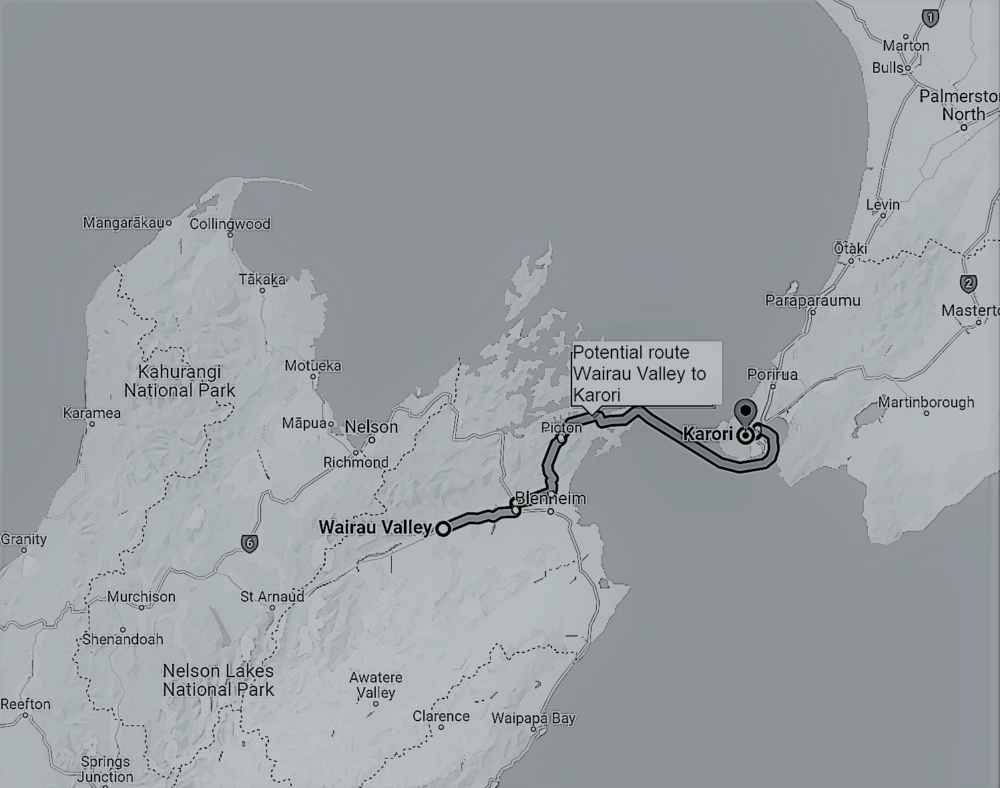

I had never taken this journey before, not one so long, apart from the ship when I left England for a new start. On this voyage, we travelled by several boats from the valley. First down the Wairau River, then across wild seas to the other island accompanied by men I barely knew.

Finally, land again, Wellington, I heard them say. Frederick once told me it was a big town, the new capital. We got off the boat, there was so much noise and so many people. The wharves were so busy: men calling out, wheeling about barrow loads of goods. Passengers standing beside their luggage trunks looking lost and scared.

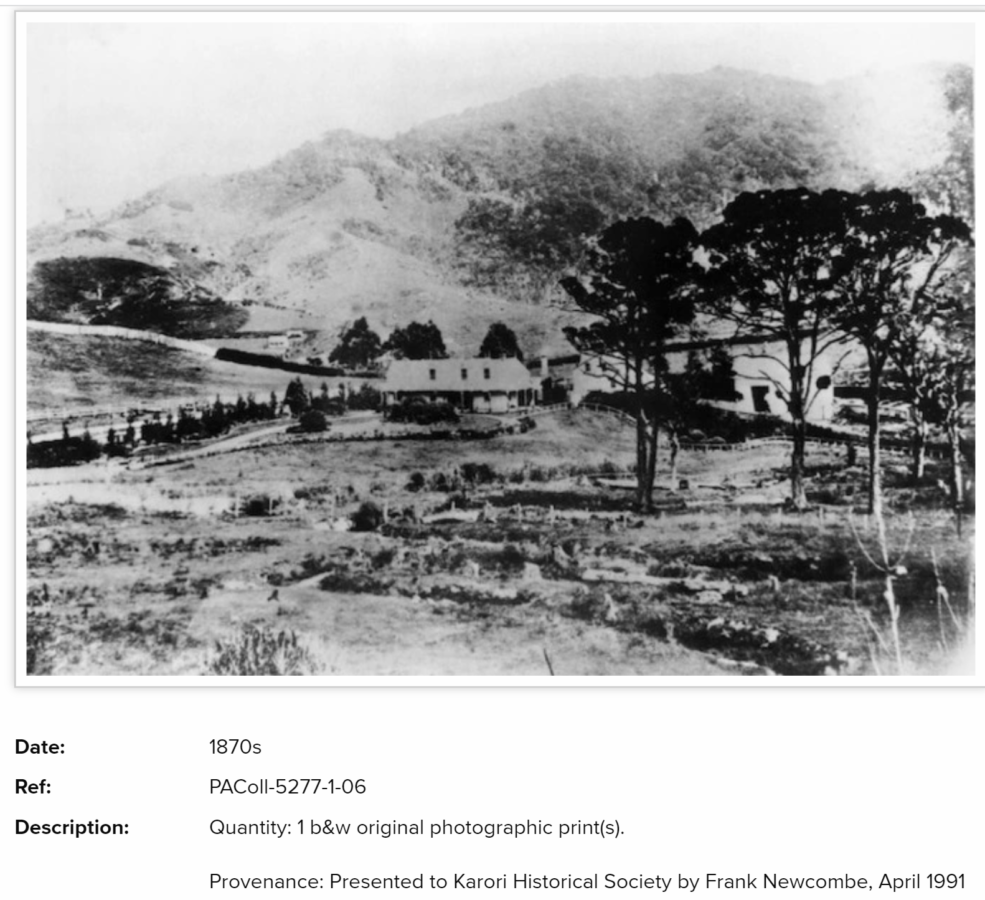

With no time to rest or take refreshment, I was rushed into a carriage and on we travelled, out along a rough and rutted road, far from the city. We passed small newly cut and cleared farm blocks, quite like the farms in the Wairau. We passed through the heavy gothic bush I had taken so long to become accustomed to the tall sky-piercing trees entwined with thick tangles of vine, and the deep, dense undergrowth you couldn’t see daylight through.

The men accompanying me speak of our destination as if I am invisible, absent. I hear Asylum; Karori Asylum. As we drew closer, I find it hard to breathe, where am I going? Why?

We drew into the long driveway, a moment of relief. Before us was a large, friendly-looking family home. The kind of home you imagine children tumbling about inside and tempting cooking smells spreading out from the kitchen. Was this it, a spell of work with a family? The closer the carriage came to the house, all the nice thoughts got pushed away. The smells, those ungodly smells hurt my nose. Then terrible sounds from inside that building found me.

Suddenly pulled out of the carriage, a gut-churning, nausea came over me. My limbs were shivering enough to make the walk up the stairs slow and difficult. Strangers were pulling me along. The urge to turn and run was futile, yet it overpowered every other thought. My teeth, clattering together, seemed to echo across the wild surrounding bush. I was voiceless. It dawned on me: this was my new forever.

Disquiet rose as I came closer to the big entrance doors. The noises enveloping me were not the endless quiet of the wild Wairau valley. That quiet was broken only by the sounds of men and women working, of animals in surrounding paddocks, and children playing. These sounds I had never heard the like of before: a cacophony, the sounds of distress, the sounds of anger, the sounds of fear.

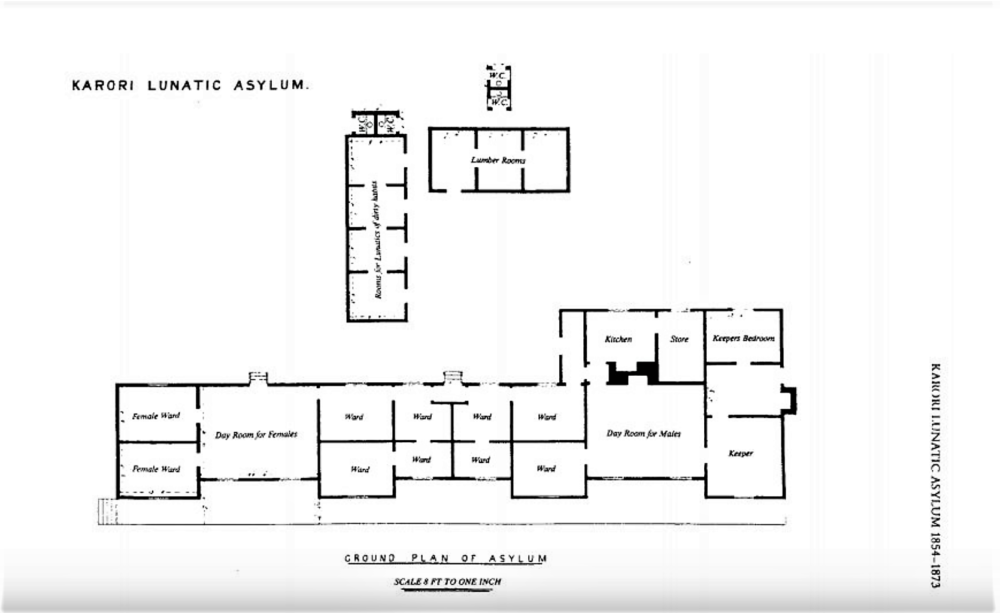

With all the courage I could muster I stepped through the large doors that opened for me. Peering down the corridors stretching out either side, the illusion of a family home disappeared. Two male voices penetrated my thoughts

“Jane Slow, 52-year-old wife of Mister Frederick Slow of the Wairau Valley. Admission for Dementia. Confirmation hereby that there is required legal certification by two Justice of the Peace and two licensed Medical Practitioners” [2] a refined male voice asserted.

That was the voice of one of the men who had brought me here. A rough male voice responded, calling for Matron. A woman suddenly appeared and, tightly gripping my arm, lead me down the corridor as the men faded away.

The woman I now know as Matron Sutherland [3] pushed me into a small room with a single wooden bed with barely a mattress on it. Roughly commanding me to change out of my simple street clothes and dress in the dirty, grey-coloured cotton shift set on the bed. I did not know then, but this was the last glimpse I had of my own clothing.

Those last remnants of my life brought to mind thoughts of my home, of the Wairua Valley, of my short time as Mrs Frederick Slow. I wondered when he would come for me. I made up my mind then to do all I could to be ready when he came. I would do this in the only way I knew: I would work hard, be strong and do all that was asked of me.

Exhausted, I ignored the disagreeable state of the bedding, the unpleasant state of the building, and collapsed on the hard bed. [3]

And now here I am, 1872, I don’t count days anymore and I don’t think I can wait much longer. The bitter chill of the winters. The cruel early morning call out to crack ice off the water trough. The cold of the kitchen before the fire heats it up. The heat of summer. That sticky humidity that takes your breath away. Days when lighting the fire in the kitchen seems to say “Jane, this is what Hades is like”.

Six years and Frederick has not come for me. No-one came for me. Alice, my sister, likely doesn’t know where I am, and I don’t know where Alice is. Who would tell her about me? Just like me, she cannot read or write. I have done all that was asked of me, and for nothing. I can’t do it much more. I’m tired.

These past years it has become too crowded, too noisy. We must share our rooms with so many people now. They try and keep the men down one end, and people who are too rough outside in small huts, but they all get to us women.

It surprises me when I see so many kinds of people here: settlers, gold miners, sailors, people who went mad on the long boat trip from their homes, even Māori men and women.[4] I had never been with the Māori people up so close. Here we are all the same, ‘mad inmates’ [5] they say.

I still help whenever I am asked, whenever I am well. I don’t mind helping. I was a domestic when I married Frederick and I am not afraid of hard work. Here it makes the days go by. We women must help, there is only the Superintendent, Matron, and their helper so it is not enough. Some of the other women refuse to help and they get into such trouble beaten or put in solitary. Better to do the jobs, I think.

This is not like home. I had to forget home. Sometimes it fills my mind even if I don’t want it to, like when I am bent over the tiny brick fire pit in the centre of the kitchen.[4] Not really a kitchen, hardly even a room, always dark even on a summer’s day. The little holes in the roof let the smoke out, which helps, but it also lets the rain in, and it rains a lot here. The kitchen floors are rotting so they get dusty in summer and slippery and muddy in winter.[6] Even if I try not to think about it, like I said, sometimes it fills my mind. I remember my kitchen: the long scrubbed wooden table where I could do the baking and prepare the meals. The big open fire with heavy pots on chains hanging each side set ready to swing over the fire.

Sometimes here when the rations are delivered, I would remember our big garden at home, all our own vegetables and meat. Now we get the same rations month after month. The only difference is how long it takes to get here. I see it in my sleep: beef, mutton, bread, rice, flour, milk potatoes, tea, sugar milk.[7] Some of that doesn’t travel too good, especially in summer. Sometimes in winter nothing gets here at all along those terrible roads. I cook the best, I can, but we all get sick of the same rations.

So many times over the years, hope swept in for nought. Posh people came and gawped at us and wrote in books. I heard them mutter about how bad things were: inhumane they said.

“A blot on humanity indeed,” Dr Buchanan said when he gave a report. [8] It must improve they said, but it didn’t.

No one ever asked me what I would like, I would have told them. A proper kitchen where I don’t have to put the plates on the floor to serve.[1] A stove, a proper stove or a proper fireplace with a place to hang the pots over the hearth.

I would have told them a bathing house where we could wash in private, hot water would be a treat even if I had to boil it over the fire. Fresh water. Yes, that would be wonderful, it is so hard to get water at all since the old well dried up. What about running water, would that be too much?[9]

But they never asked me and things never got better. Matron and Mr Sutherland got into trouble and we did not get hit with the broom handle or get put in solitary for a while.[10] One day they took them away and the new people came. We don’t leave though, unless it’s in a box, that’s the only way out. If I was in jail I would have been given a sentence and be set free, not here, this is a life sentence.” [11]

On 10th December 1872, Jane Slow died. Her final moments witnessed not by loving family and friends but recorded by the Undertaker. ‘Jane Slow. Female 56 years. Debility and Decay.’[12]

Now, in 2021, no other record remains. The government archivist replying to a request for her records informing that “no reference to a Jane Slow was located”.

Yet at the time of Jane’s death, change was coming. Life in Karori improved a little after 1872 and it was finally closed in 1875. Those remaining were moved into new premises: the Mount View Asylum in the centre of Wellington (now part of Government House) [13]. The Karori building was designated as a school,[14] however parents refused to have their children attend until improvements were made to the building. It took two years of work until it became and remains a school.[15]

Treatment and approaches to people with mental illnesses changed significantly from that time. Jane’s diagnosis of “dementia” was not the forms of dementia we understand today. It is possible it was a form of what we now describe as Schizophrenia but could also have been a behavioural issue.[16] There was little separation between those with social and behavioural issues from those with chronic mental illness. Rarely was treatment provided and conditions that caused people to be locked away in those times would in many instances nowadays be treatable or not considered illness, such as poverty and menopause. [17] The newspaper report that Jane had ‘long periods of sanity’ suggests today she would be living in the community.[18]

Change was also coming for the participation of women in political processes enabling the progress of rights for women. In America in 1872, the year Jane died, Susan B Anthony was arrested and charged with illegal voting, one of the many new voices of and for women[19] Ten years later in New Zealand on 28 July 1893, a landmark petition containing the signatures of 24,000 women was collected by Kate Shepherd and a group of women suffragists and presented to parliament.[20] In September that same year, New Zealand women would be first in the world to have a political voice: the right to vote.[21]

Jane Slow was likely my three times Great Grandmother’s sister. Historically invisible we can’t be sure Jane is the woman her descendants believe she is. We believe she was born in England as Jane Handley (Hanley) and came to New Zealand with her sister Alice in 1855. Early in 1861 she moved to the Wairau Valley (verified by a letter from Father Garin of Nelson) and married Frederick Slow in 1861[22] becoming Jane Slow. From the brief records we have, one can only imagine who Jane was and how her life was lived, her strength and resilience in what were inhumane conditions.

For many women of the 19th century, we can only gather scant records through which we see the humanity and history of women such as Jane. It is a reminder of the struggle for the rights of women and changes in the treatment and understanding of mental illness that we now have in the 21st century.

Melanie Atkins 2021

BIBLIOGRAPHY

The story of Jane Slow and her life in the Asylum is based on fact including reports of conditions in the Asylum at the time. I have found no records that describe Jane’s actual experience though she was present through the years reported.

[1] W. H. Williams, ‘Far From the Maddening Crowd Karori Lunatic Asylum 1854 – 1873’, N. Z. Leg., vol. 2, no. 3, pp. 16–18, 1990.

[2] H. Kuglin, ‘Mental illness in the 19th century Wellington region / by Heidi Kuglin’, New Zealand genealogist, May/Jun 2009; v.40 n.317:p.113-115; issn:, 00:00 1200. https://natlib.govt.nz/records/20850409 (accessed Sep. 06, 2021).

[3] ‘Karori Lunatic Asylum Inquiry.’, Wellington Independent, vol. XXVIII, no. 3453, p. 2, Apr. 27, 1872.

[4] R. Ridley-Smith, ‘The Karori Lunatic Asylum Transcribed History’.

[5] ‘Spagnuolo on Coleborne, “Insanity, Identity and Empire: Immigrants and Institutional Confinement in Australia and New Zealand, 1873-1910” | H-Disability | H-Net’. https://networks.h-net.org/node/4189/reviews/1238350/spagnuolo-coleborne-insanity-identity-and-empire-immigrants-and (accessed Feb. 13, 2022).

[6] ‘The Nelson Evening Mail. Thursday, December 14, 1871. , the Nelson Evening Mail. Thursday, December 14, 1871.’, Nelson Evening Mail, vol. VI, no. 295, p. 2, Dec. 14, 1871.

[7] M. Pokia, M. Christmas, and M. Guest, ‘Karori Asylum Family Research Pg 5-6’, p. 9.

[8] ‘The Lunatic Asylum at Karori. , the Lunatic Asylum at Karori.’, Wellington Independent, vol. XXVI, no. 3347, p. 2, Nov. 16, 1871.

[9] ‘Joint Committee Evidence into Lunatic Asylums’, Nelson Evening Mail, Nelson, Dec. 14, 1871. [Online]. Available: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NEM18711214.2.7

[10] ‘The Karori Asylum Assault Cases.’, Evening Post, vol. VIII, no. 107, p. 2, Jun. 07, 1872.

[11] Walters Laura and Kenny Katie, ‘Through the Maze Chapter 1’, Through the Maze Our Mental Health Journey. https://interactives.stuff.co.nz/2017/through-the-maze/chapterOne/ (accessed Sep. 06, 2021).

[12] ‘Slow Jane Death Certificate 1872’, Karori Asylum, Wellington, New Zealand, Dec. 10, 1872.

[13] ‘The Mount View Lunatic Asylum | NZETC’. http://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-Cyc01Cycl-t1-body-d4-d20-d9.html (accessed Sep. 26, 2021).

[14] ‘Conquering Karori’, Stuff, Jul. 30, 2011. https://www.stuff.co.nz/dominion-post/capital-life/5364822/Conquering-Karori (accessed Feb. 13, 2022).

[15] ‘Karori Local History Suburb Guide’. https://www.wcl.govt.nz/heritage/karori.html (accessed Sep. 26, 2021).

[16] S. A. Hill and R. Laugharne, ‘Mania, dementia and melancholia in the 1870s: admissions to a Cornwall asylum’, J. R. Soc. Med., vol. 96, no. 7, pp. 361–363, Jul. 2003.

[17] ‘Outrageous ways to be admitted to an insane asylum in the 19th century’, NZ Herald. https://www.nzherald.co.nz/lifestyle/outrageous-ways-to-be-admitted-to-an-insane-asylum-in-the-19th-century/W4G5JGTSL22X4BHZXTLUUZUAY4/ (accessed Sep. 06, 2021).

[18] ‘Costs of Karori Marlborough Provincial Council’, Marlborough Express, Marlborough, May 04, 1872. Accessed: May 20, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MEX18720504.2.13?end_date=27-12-1872&items_per_page=10&phrase=2&query=jane+slow&snippet=true&start_date=01-01-1872

[19] ‘In 1872, Susan B. Anthony Was Arrested for Voting “Unlawfully” | Smart News | Smithsonian Magazine’. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/why-susan-b-anthony-was-arrested-1872-180975587/ (accessed Sep. 26, 2021).

[20] ‘Massive women’s suffrage petition presented to Parliament’. https://nzhistory.govt.nz/womens-suffrage-petition-presented-to-parliament (accessed Sep. 21, 2021).

[21] ‘Suffrage 125 | Ministry for Culture and Heritage’. https://mch.govt.nz/suffrage-125 (accessed Sep. 26, 2021).

[22] ‘White Jane Slow Frederick Marriage 1861’, Wairau Valley, South Island, New Zealand, Jul. 08, 1861.