The Birth of Euphemia Julia

Gold captures imaginations, enticing people to set off on epic journeys in search of riches. In the 19th century, people crisscrossed the oceans of the world in search of the gold that would give them a better life. There were women who made the journey and were overwhelmed by the new country, and there were women who embraced the adventure. This story is to acknowledge one such woman – Alice Handley Appoo Clark – who far from her homeland created a new life for herself and her family, and ultimately her descendants, of which I am one.

In the mid-nineteenth century gold was discovered on the land of the Dja Dja Warrung [1]people in northern Victoria, Australia. Hundreds of thousands of people arrived in Australia from all over the world and made the arduous journey to the Victorian Goldfields. The recorded stories were more often about the men: of their exploits: their sudden riches and equally sudden downfall: the swashbuckling adventures of travelling across the globe: their criminal behaviour and gallant achievements. Rarely heard were the stories from the local Dja Dja Warrung people, the miners from China, and the women who arrived on the fields either alone, or more often with their husbands and children.

As an adult, after marriage, childbirth, and career, the life of Alice and women like her drew me in. Only whispers of her life and records remain yet piecing together what can be found reveals a woman of strength and resilience. Alice arrived in Back Creek, Amherst from New Zealand between 1858 and l859, with, or possibly in search of her husband. Alice and her small children made the hazardous journey to the Victorian Goldfields.

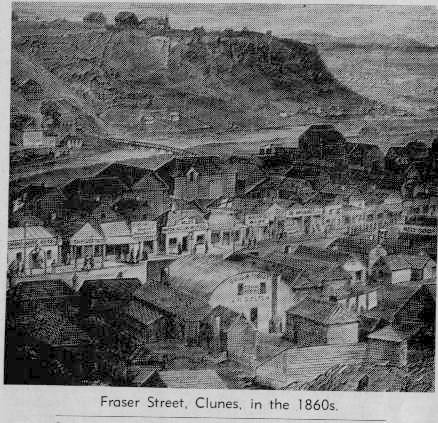

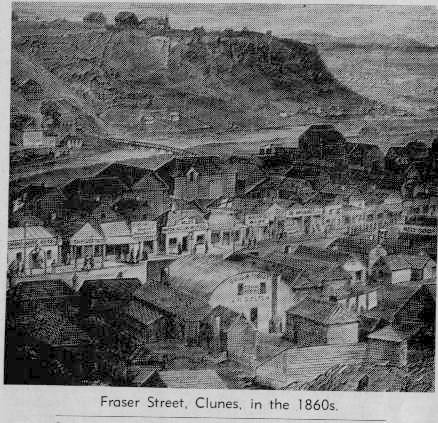

On a bleak winter’s weekend in June 2022, with an Antarctic chill sweeping the state, I too visited the Victorian Goldfields to explore what I could of Alice and her husband, John Jacobus Appoo. Leaving the steamy warmth of my car, holding tight to an umbrella that was turning inside out as the wind drove rain down the main street, I quickly run into the brightly lit, heated Clunes Museum. Thoughts of 1861 are poking through my chilled mind as I make my way to the encompassing warmth of the library. To live in these conditions in a tent, or at best a rudimentary wooden dwelling, is hard to contemplate. To also give birth in such a situation is unimaginable.

I noted that my visit was a month before Euphemia Julia Appoo (my 2X great-grandmother)[2] was born in 1861. Despite my cosy surroundings; my recollections of 1970s obstetric nursing; and my comfortable modern life; I set myself the task of imagining that day of birth, 11th July 1861.

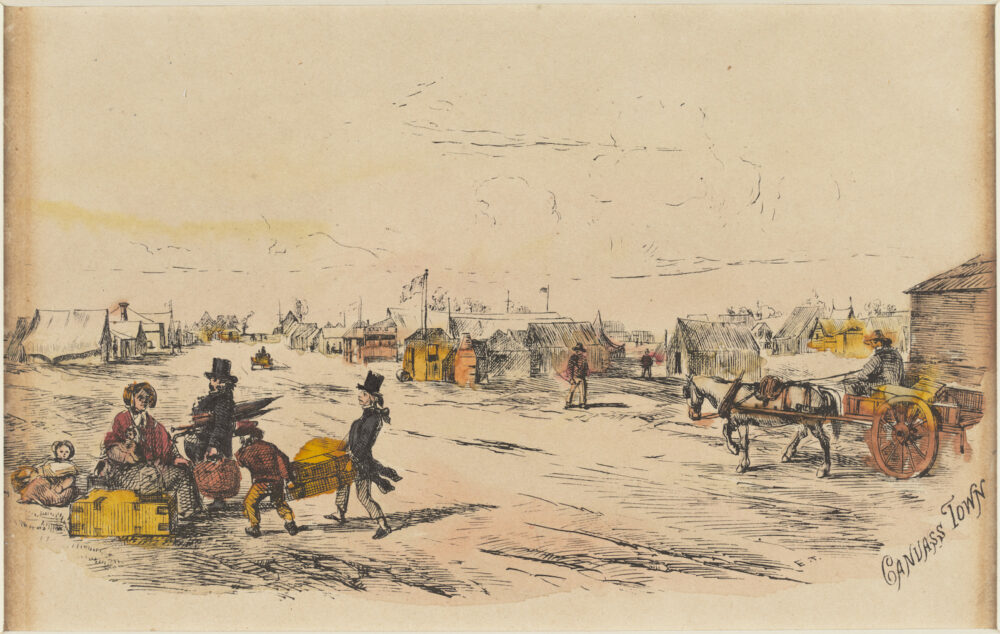

Having left her home in England only a few years before, Alice would likely still be unused to the upside-down seasons. Instead of warm summer days, July in Australia is often the coldest month. Hopefully, the new exotic wildlife enchanted and excited her – the brilliant colours and sounds of birdlife giving pleasure amid the squalor and overcrowding of 50,000 people living in tents or simple dwellings around her. [3]

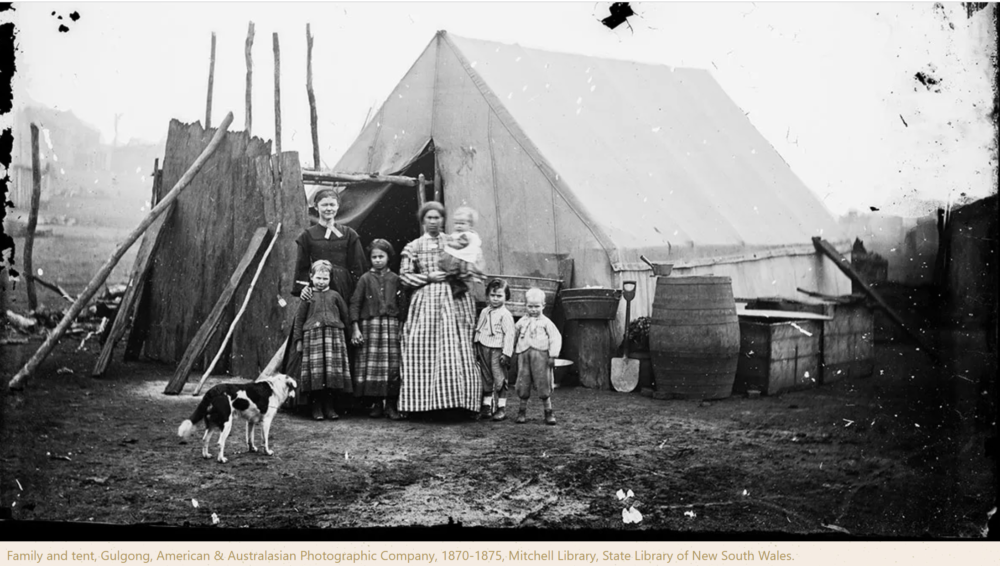

A drought in preceding years[4][5] had created a dusty brown summer landscape – red-brown earth, dry brown grass, and scattered eucalypt gums struggling in the newly cleared lands. July 1861 arrived with “unfavourable weather” and rain that fell “in sufficient abundance. “ [5] turning the dry dusty landscape into torrents of mud. The exhausting, gasping heat of summer was supplanted by bone-chilling winter temperatures with blustering winds whipping the rain into painful shards.

One-room canvas and bark houses, or (more commonly) canvas tents, offered little protection. Alice’s senses were likely bombarded with the sounds of a seething land, never quiet. The sounds of life being lived: the drunks, the arguments, the children playing, women birthing, dogs barking, birds squawking, the machines driving deep into the earth.

Surrounded by all this Alice prepared to give birth. Such a different experience from the 21st-century hospital as a birthplace. Such a different experience to that of the local indigenous women in earlier times, prior to the arrival of settlers and miners. It was said the local Dja Dja Wurrung women gave birth in the shelter of a huge tree, protected from the weather, and supported by other women. In winter cocooned in warm possum skins.[7]

For Alice there was no Doctor or hospital, only a woman hopefully experienced in childbirth, to care for her. With no mother or family, and her husband recently dead, Alice likely had no idea of where income or support would come from. As a witness to Julia’s birth (and other life events for Alice), I hope Euphemia Goodfellow was the birth support, midwife, doula for Alice. [2]

Before the pain of childbirth concentrated Alice’s thoughts, she no doubt thought about past experiences. Birth and death were not new to Alice, her first baby died before they left England [8] her previous baby had died the year before[9]. On the Goldfields the earthy and roaring sounds of childbirth would echo through the camp. A neighbour could hear progress by the escalating sounds, the encouragement and instruction of the women supporters, and the outcome with sounds of joy or the silence of death. The high risk of death for mother and baby was a familiar experience for women, at that time. [10][11]

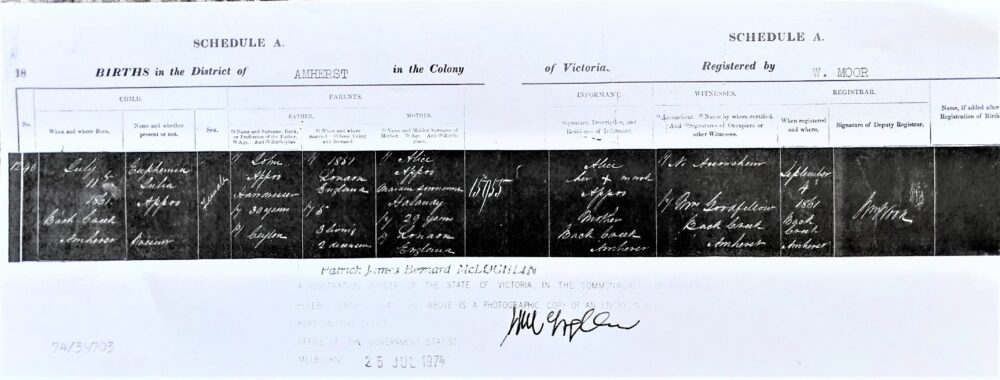

There is no record of where Alice gave birth, or who was with her. Through government birth records we know this time mother and baby survived. On the 11 July 1861 Alice gave birth to a baby girl Euphemia Julia Appoo.[2]

In the past I had not even considered the lives of women. Absent from recollections, women were a behind-the-scenes description; the person who tended the home, raised the children, cared for the men, while life and adventure happened elsewhere. The craft of establishing a home, raising children on the goldfields, and childbirth were rarely recorded.

In the years following Julia’s birth at least three more children were born to Alice and her new husband[12]. Living in the newly established township of Clunes the family would have been surrounded by the increasingly mechanised mining but also the towering Eucalypt trees with their crisp clean scent and blue summer haze. Alice’s children would grow up familiar with the land, with native flowers and grasses blooming, with the animals once strange to Alice – kangaroo, possum, snake, and with the birds – noisy, crested, and colourful. A new life and family in a new land.[4]

I would like to thank the people at the Talbot museum who so generously gave their time to assist with my research and provide me with information on life on the Goldfields.

REFERENCES

[1] S. A. T. Creative, ‘Dhelkunya Dja’. https://www.dhelkunyadja.org.au/ (accessed Aug. 16, 2022).

[2] ‘Appoo Euphemia Julia Birth Certificate’. Births Deaths Marriages Victoria, Jul. 11, 1861. [Online]. Available: https://my.rio.bdm.vic.gov.au/efamily-history

[3] R. Hull, Talbot Borough Jubilee 1858 – 1908. Talbot Leader, 1908.

[4] ‘Drought and Water Supply.’, Mount Alexander Mail, Victoria, Feb. 12, 1858. Accessed: Aug. 16, 2022. [Online]. Available: http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article197085765

[5] ‘Weather and Rainfall’, Age, Melbourne, Victoria, Jul. 12, 1861. Accessed: Aug. 16, 2022. [Online]. Available: http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article154901651

[6] ‘Conditions | Ergo’. https://ergo.slv.vic.gov.au/explore-history/golden-victoria/life-fields/conditions (accessed Aug. 16, 2022).

[7] D. Frankel and J. Major, Victorian Aboriginal life and customs through early European eyes, 1st ed. La Trobe eBureau, 2017. doi: 10.26826/1004.

[8] ‘Appoo Elizabeth Sylvia 1853 death certificate’.

[9] ‘Appoo John Bestian 1860 Death cert’.

[10] R. Taylor, M. Lewis, and J. Powles, ‘The Australian mortality decline: all-cause mortality 1788–1990’, Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 27–36, 1998, doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842X.1998.tb01141.x.

[11] D. Beechey, ‘Eureka! Women and birthing on the Ballarat goldfields in the 1850s’, Thesis, ACU Research Bank, 2003. doi: 10.26199/5d7afd641b752.

[12] ‘Clark Births Victoria Australia’.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

E. Clacy, A Lady’s Visit to the Gold Diggings of Australia in 1852-53. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781139109017.

‘Adelaidia 19th Century Childbirth’. https://adelaidia.history.sa.gov.au/subjects/19th-century-childbirth (accessed Apr. 15, 2022).

‘Book, Richard Aitken, Talbot & Clunes Conservation Study Part B, 1988’, Victorian Collections. https://victoriancollections.net.au/items/5b6292bc21ea6e05488c515b (accessed Aug. 16, 2022).

G. Chamberlain, ‘British maternal mortality in the 19th and early 20th centuries’, J. R. Soc. Med., vol. 99, no. 11, pp. 559–563, Nov. 2006.

‘CANVASS i.e. Canvas TOWN’, State Library Victoria. http://handle.slv.vic.gov.au/10381/95477 (accessed Nov. 27, 2022).

‘Climate statistics for Australian locations’. http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/averages/tables/cw_088104.shtml (accessed Jun. 07, 2022).

S. Davenport, ‘Diary, 1841-1846. [manuscript].’ 1841. Accessed: May 14, 2022. [Online]. Available: http://handle.slv.vic.gov.au/10381/256333

S. T. Gill, Diggers hut canvas & bark Gill, S. T., 1818-1880, artist. Date 1869. 1869. Accessed: Sep. 27, 2021. [Watercolour]. Available: http://handle.slv.vic.gov.au/10381/292889

‘Eliza Perrin: An “Ordinary” Woman of the Goldfields’, Gold Museum, Ballarat, Feb. 08, 2013. http://www.goldmuseum.com.au/eliza-perrin-an-ordinary-woman-of-the-goldfields/ (accessed May 14, 2022).

H. D. Harris, Eureka Victorian Goldfields Research in Landfall in southern seas. Christchurch, N.Z.: Christchurch Congress Organising Committee of the New Zealand Society of Genealogists, 1997.

‘Family and Tent Image SBS – Gold’. https://www.sbs.com.au/gold/ (accessed Nov. 27, 2022).

L. Vallone and J. H. McGavran, ‘Fertility, Childhood, and Death in the Victorian Family’, Vic. Lit. Cult., vol. 28, no. 1, pp. 217–226, 2000.

‘Giving Birth in the Bush FINAL V1.0 AJ 20191217.pdf’. Accessed: Jun. 06, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://prov.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/files/Provenance/Provenance%202019%20Giving%20Birth%20in%20the%20Bush%20FINAL%20V1.0%20AJ%2020191217.pdf

‘Historic-gold-mining-sites-in-the-south-west-region-of-Victoria-Bannear-1999.pdf’. Accessed: Aug. 16, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.heritage.vic.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0022/512257/Historic-gold-mining-sites-in-the-south-west-region-of-Victoria-Bannear-1999.pdf

I. Loudon, ‘Maternal Mortality in Britain from 1850 to the Mid-1930s’, in Death in Childbirth, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198229971.003.0015.

‘Sarah Davenport: a working woman at the diggings- Gold Rush’, Old Treasury Building, Jun. 21, 2018. https://www.oldtreasurybuilding.org.au/sarah-davenport-diggings/ (accessed Apr. 30,2022).

‘SBS — Gold’. https://www.sbs.com.au/gold/ (accessed May 14, 2022).

L. Radford, ‘The Reality of Childbirth in the 1800s’, Curious Historian. https://curioushistorian.com/the-reality-of-childbirth-in-the-1800s (accessed Dec. 05, 2021).

D. of H. Cultural Heritage Unit, ‘Women – Concept – Electronic Encyclopedia of Gold in Australia’. https://www.egold.net.au/biogs/EG00115b.htm (accessed Apr. 30, 2022).

‘Women on the goldfields | Ergo’. https://ergo.slv.vic.gov.au/explore-history/golden-victoria/life-fields/women-goldfields (accessed Apr. 30, 2022).

‘Women on the Goldfields Part 1 – 19th Century Womanhood’, Sovereign Hill Education Blog, Apr. 24, 2020. https://sovereignhilledblog.com/2020/04/24/women-on-the-goldfields-part-1-19th-century-womanhood/ (accessed Apr. 30, 2022).